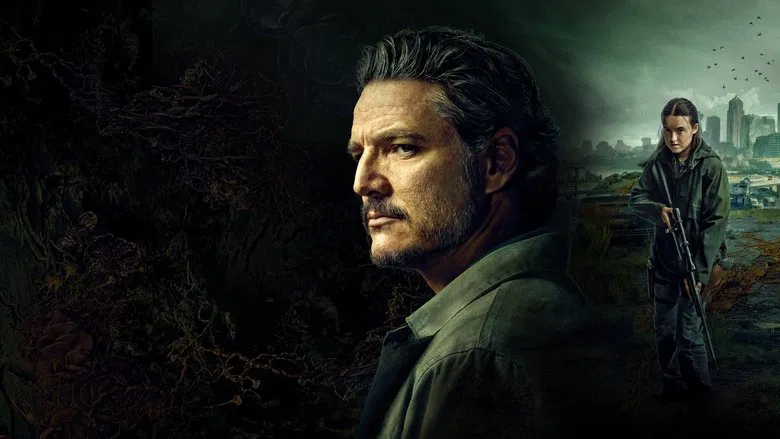

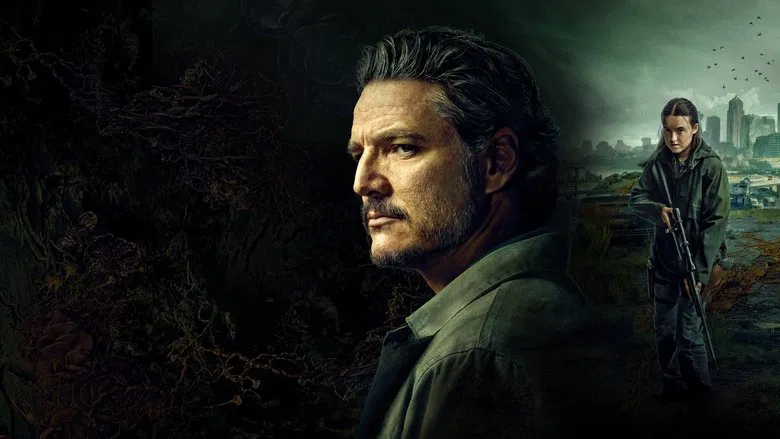

The Architecture of LossFor decades, the "video game adaptation" was a cinematic graveyard—a place where nuance went to die, buried under the weight of fan service and hollow spectacle. The fundamental problem was always translation: how do you take a medium predicated on player agency and transpose it into one defined by directorial control? The answer, as delivered by showrunners Craig Mazin (*Chernobyl*) and Neil Druckmann in HBO’s *The Last of Us*, is to stop trying to replicate the gameplay and instead excavate the soul. This is not a series about zombies, nor is it really about a cure. It is a brutal, tender, and often devastating treatise on the terrible things love compels us to do.

From a visual standpoint, the series rejects the glossy, high-contrast action beats typical of the genre in favor of what Mazin calls "organic cinematic naturalism." The camera, often handheld and intimate, lingers on the decay of the American West not as a horror show, but as a quiet tragedy. The production design creates a suffocating sense of reality; nature has reclaimed the suburbs of Boston and the highways of Kansas City, turning the familiar into the alien. The violence, when it comes, is clumsy and desperate. There are no heroes here, only survivors whose morality has been eroded by twenty years of trauma. The infected—the "clickers" with their fungal blooms—are terrifying precisely because they are treated as a biological fact rather than a supernatural evil. They are the backdrop, not the story.

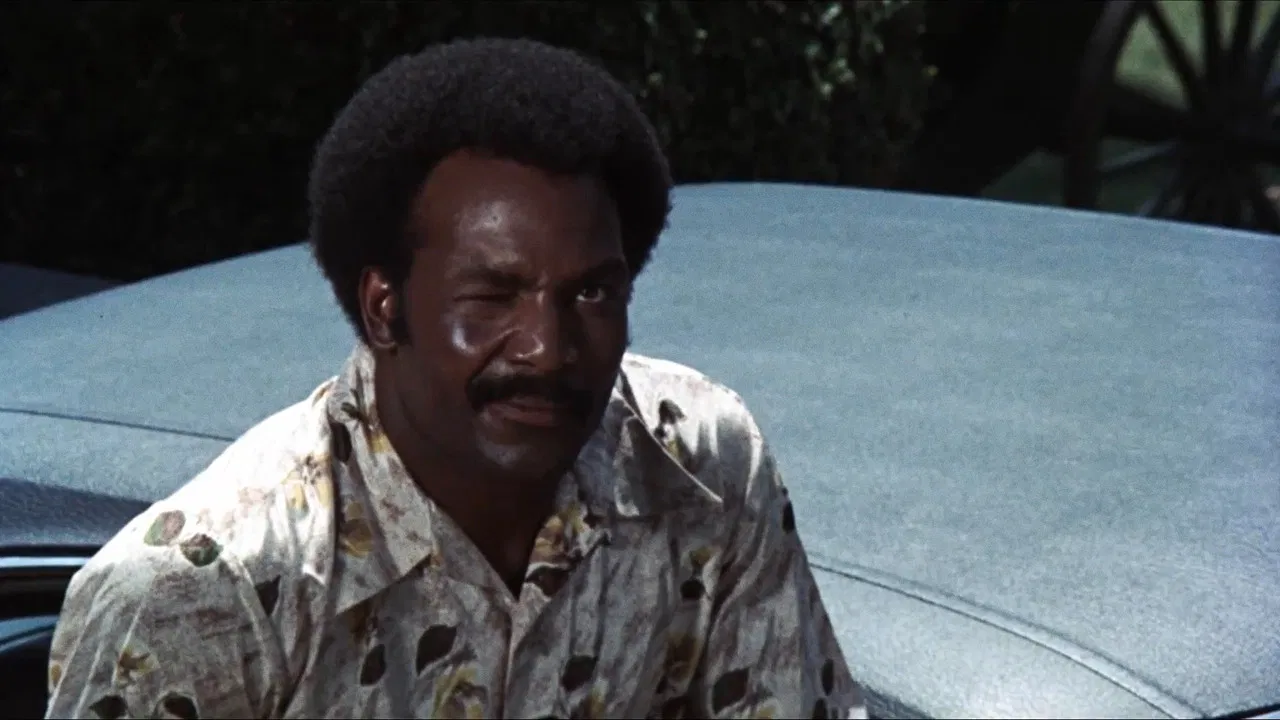

The story belongs entirely to the spaces between the action. Pedro Pascal’s Joel is a man whose heart has calcified; his performance is a masterclass in physical repression, conveying volumes with a shifted jaw or a averted gaze. He is the perfect foil to Bella Ramsey’s Ellie, whose profane, jagged vulnerability pierces through his defenses. Their journey across a broken America is less about reaching a destination and more about the slow, painful thawing of Joel’s grief.

Nowhere is the show’s ambition more evident than in its third episode, "Long, Long Time." Diverging sharply from the source material, the narrative pauses the main quest to tell a self-contained story of Bill (Nick Offerman) and Frank (Murray Bartlett). It is a quiet revolution in storytelling—a tender, decades-spanning romance found at the end of the world. By shifting focus from survival to *living*, the series argues that the apocalypse is not just about what is lost, but what can still be found. It reframes the entire series: we aren't watching Joel and Ellie survive just to breathe another day; we are watching them learn why breathing is worth the effort.

Ultimately, *The Last of Us* transcends its origins because it refuses to sanitize the ugliness of its characters. It posits that love is not always a redeeming force; it can be selfish, destructive, and violent. By the time the credits roll on the final episode, the viewer is left with a profound sense of unease. We have witnessed a technical breakthrough in television, yes, but more importantly, we have looked into the abyss of human attachment and seen exactly what stares back. It is a masterpiece not because it mimics a game, but because it understands exactly what it means to be human when humanity itself is gone.