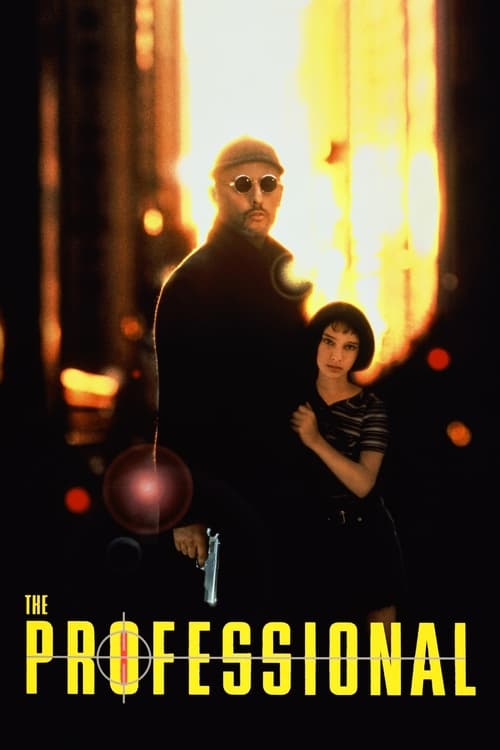

The Violent Innocence of a Concrete JungleIt is a rare feat for a film to be simultaneously a masterclass in action cinema and a subject of profound discomfort. Luc Besson’s *Léon: The Professional* (1994) occupies this precarious space, balancing on the razor's edge between stylized violence and a deeply problematic, yet undeniably tender, human connection. It is a fairy tale dipped in acid—a story of a knight and a princess where the castle is a cramped Little Italy apartment and the dragon is a drug-addled DEA agent. To view it today is to wrestle with its legacy: a technical marvel that feels increasingly transgressive in its central relationship.

Besson’s visual language here is not merely a backdrop; it is the suffocating atmosphere of the film itself. Working with cinematographer Thierry Arbogast, Besson creates a New York that feels less like a city and more like a labyrinth of shadows and sunlight. The camera clings to tight spaces—corridors, stairwells, and the sparse sanctuary of Léon’s apartment. The aesthetic is pure *Cinéma du look*: slick, hyper-real, and operatic. When violence erupts, it is not messy; it is balletic and precise, mirroring the internal order of Léon’s mind. The opening sequence alone establishes this, portraying the hitman not as a murderer, but as a phantom force of nature, disappearing into the shadows just as effectively as he emerges from them.

However, the film’s emotional weight—and its controversy—rests entirely on the shoulders of its two leads. Jean Reno’s Léon is a study in arrested development; he is a lethally efficient killer with the emotional intelligence of a child, drinking milk and tending to his aglaonema plant as if it were a religious sacrament. Into this sterile orbit crashes Mathilda (a revelatory, pre-teen Natalie Portman). The tragedy of Mathilda is that she has been forced to bypass childhood entirely, hardening into a cynical adult before she even hits puberty. The dynamic is famously uncomfortable, teeming with a tension that modern audiences often find borderline predatory, yet the film frames it as two broken souls attempting to heal one another. They are orphans of the world, clinging to each other because the alternative is the void.

If Léon and Mathilda represent a quiet, desperate love, Gary Oldman’s Norman Stansfield represents the noise of pure chaos. Oldman’s performance is legendary not for its nuance, but for its absolute lack of restraint. In the now-iconic scene where he murders Mathilda’s family, Stansfield treats the massacre like a symphony, popping pills and discussing Beethoven with a terrifying casualness. He is the antithesis of Léon: where the hitman is professional and silent, the cop is erratic, loud, and corrupt. Oldman allows the audience no safety; his presence on screen signals that the rules of the civilized world have been suspended.

Ultimately, *Léon: The Professional* remains a complicated artifact. It functions brilliantly as a thriller, elevating the "hitman with a heart of gold" trope into something mythic. Yet, it is impossible to divorce the film from the unease of its central romance, a narrative choice that speaks to the director's provocations as much as his storytelling. It is a film about the loss of innocence that inadvertently questions the innocence of the camera itself. We are left with a story that is as visually stunning as it is morally murky—a portrait of love and death in a city that has no time for either.