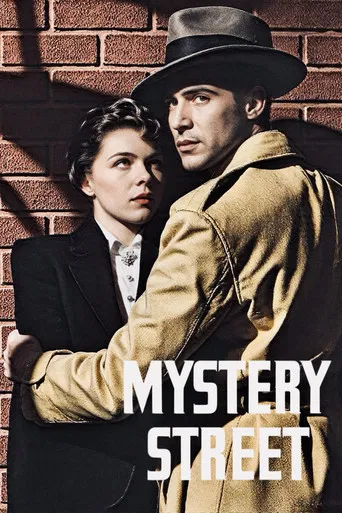

The Starlet as SurvivorIf cinema is a dream machine, then Ti West’s *MaXXXine* is the waking nightmare that follows the fever. Completing a trilogy that began with the grainy, heat-stroke exploitation of *X* and the Technicolor manic-depression of *Pearl*, this final installment shifts the lens to 1985 Los Angeles. Here, the horror is no longer hidden in a rural Texas farmhouse; it is broadcast on every billboard and televangelist sermon in the city. West has constructed not just a slasher sequel, but a scathing, neon-soaked essay on the predatory nature of ambition.

Visually, the film abandons the 1970s grit of its predecessor for the glossy, synthetic sheen of the VHS era. West operates in the language of *Giallo*—black leather gloves, pulsing synth scores, and blood that looks candy-apple bright against the grime of the Sunset Strip. The aesthetic is oppressive, a suffocating layer of "style" that mirrors the protagonist’s internal state. Los Angeles is depicted not as a city of angels, but as a sprawling, sun-bleached purgatory where the Satanic Panic and the Night Stalker serve as background radiation to the real threat: the industry itself. The camera prowls through video rental stores and backlots with a fetishistic gaze, suggesting that in Hollywood, being watched is the price of admission.

At the center of this hurricane is Mia Goth, who has quietly delivered one of the most athletic and complex acting feats in modern horror. As Maxine Minx, she is the antithesis of the traditional "Final Girl." She does not survive because she is pure; she survives because she is ruthless. The film’s emotional core lies in the friction between Maxine’s traumatic past (the massacre of *X*) and her refusal to be defined by it. When she repeats her mantra—"I will not accept a life I do not deserve"—it sounds less like an affirmation and more like a threat directed at the universe. The narrative eventually untangles a web involving her estranged father, a televangelist whose moral crusades mask a deep rot, turning the third act into a violent confrontation between religious repression and libertine fame.

Ideally, a trilogy closer should tie up loose ends, but *MaXXXine* is more interested in severing them. The narrative occasionally buckles under the weight of its own subplots—private investigators, satanic cults, and film-within-a-film meta-commentary jostle for space. Yet, this messiness feels intentional, reflecting the chaotic, cocaine-fueled ego of the decade it satirizes. While it lacks the devastating, intimate tragedy of *Pearl*, it succeeds as a portrait of survival at a terrible cost. In the end, West suggests that the only way to kill the monsters of your past is to become a bigger, brighter monster yourself. Hollywood loves a killer, as long as she hits her mark.