✦ AI-generated review

The Unbearable Lightness of being Stupid

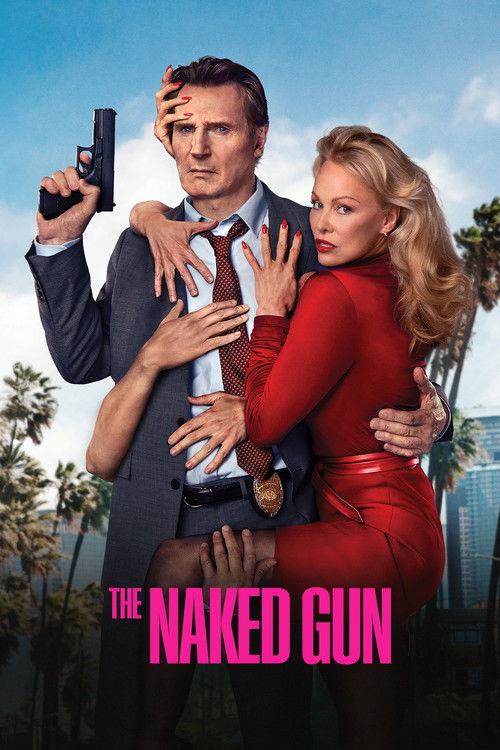

For the better part of a decade, the theatrical comedy has been gasping for air, suffocated by the twin pressures of streaming algorithms and a cultural climate that demands every piece of art "say something." We have forgotten the communal sanctity of the belly laugh, that specific, involuntary convulsion shared by strangers in a dark room. Into this vacuum steps Akiva Schaffer’s *The Naked Gun* (2025), a film that boldly dares to be about absolutely nothing other than the mechanics of a joke. By resurrecting the anarchic spirit of the Zucker-Abrahams-Zucker (ZAZ) empire, Schaffer hasn't just rebooted a franchise; he has reminded us that stupidity, when executed with precision, is a high art.

To view this film merely as a "legacy sequel" is to miss the distinct texture of its absurdity. Yes, Liam Neeson plays Frank Drebin Jr., son of Leslie Nielsen’s iconic bumbling detective, and yes, the plot—involving a "P.L.O.T. Device" (Primordial Law Of Toughness) stolen by a technocratic villain—is merely a clothesline on which to hang gags. But Schaffer, a veteran of The Lonely Island’s surrealist school, understands that the soul of a spoof lies not in the reference, but in the reaction. The film’s visual language mimics the polished, blue-tinted seriousness of modern action thrillers (think *John Wick* or Neeson’s own *Taken* oeuvre), creating a friction that makes the slapstick detonate with greater force. When Drebin Jr. engages in a "gun-fu" battle, not by firing bullets, but by violently ejecting empty magazines into the faces of his enemies, the film is doing double duty: it is providing a kinetic sight gag while simultaneously skewering the fetishistic gunplay of contemporary cinema.

The film’s beating heart, however, is Neeson. It would have been easy for the actor to coast on a "wink-wink" performance, letting the audience know he’s in on the joke. Instead, Neeson commits to a level of stone-faced gravitas that borders on the pathological. He plays Drebin Jr. not as a clown, but as a man burdened by a competence he does not possess. There is a profound loneliness to his stupidity. When he infiltrates a bank disguised as a schoolgirl, his posture remains that of a weary, grizzled veteran; the disconnect between his internal monologue and his external reality creates a character study in delusion. Unlike Nielsen, whose Drebin was often a cheerful agent of chaos, Neeson’s Drebin is a stoic tragedy, which makes his inevitable pratfalls feel earned, almost fateful.

Schaffer also wisely allows the supporting cast to breathe within this suffocating reality. Pamela Anderson, returning to the screen as the femme fatale Beth Davenport, offers a performance of surprising warmth and impeccable timing. Her scat-singing sequence is not just a funny interlude; it is a moment of pure, unadulterated commitment that mirrors the film’s ethos: go big or go home.

Ultimately, *The Naked Gun* succeeds because it rejects the modern impulse to be "meta" or self-aware. It does not apologize for its existence. In a cinematic landscape cluttered with universe-building and heavy-handed social commentary, watching Frank Drebin Jr. drive an electric car while it is still plugged into the station—dragging the precinct wall down the street behind him—feels like a radical act of liberation. The film asserts that sometimes, the most human thing we can do is laugh at a man falling down, provided he does it with enough dignity to break the floorboards.