The Law of the Jungle in Lip GlossTo dismiss *Mean Girls* (2004) as merely a "teen comedy" is to ignore one of the most astute sociological studies of the early 21st century. Adapted by Tina Fey from Rosalind Wiseman’s nonfiction parenting guide *Queen Bees and Wannabes*, the film functions less as a lighthearted romp and more as a field recording of a brutal ecosystem. Director Mark Waters and Fey understood a fundamental truth that many peers in the genre missed: high school is not a time of innocence; it is a primal struggle for territory, dominance, and survival.

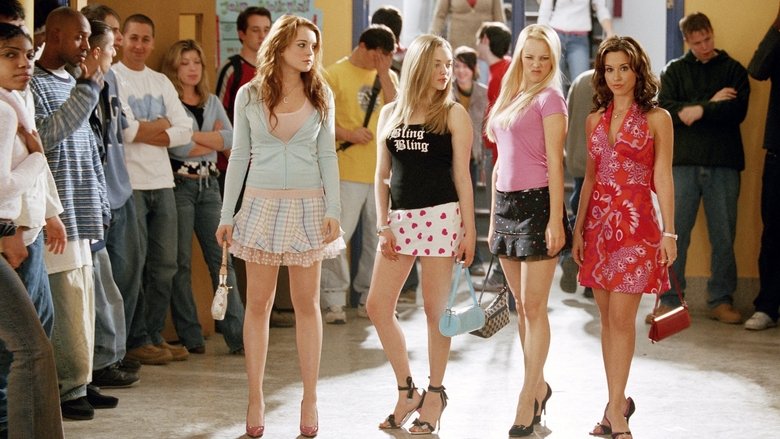

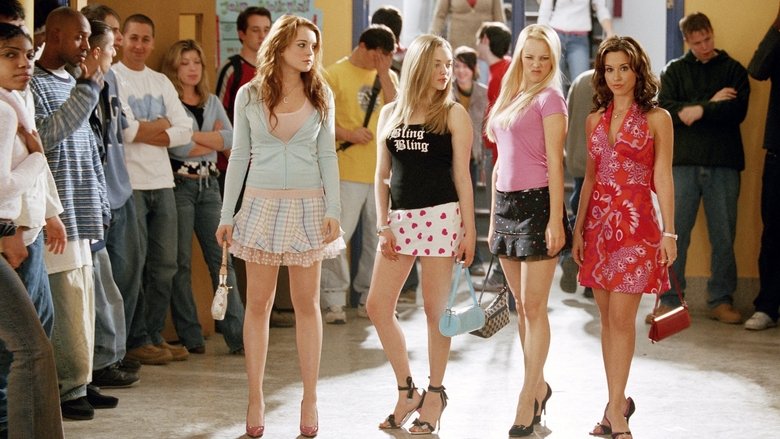

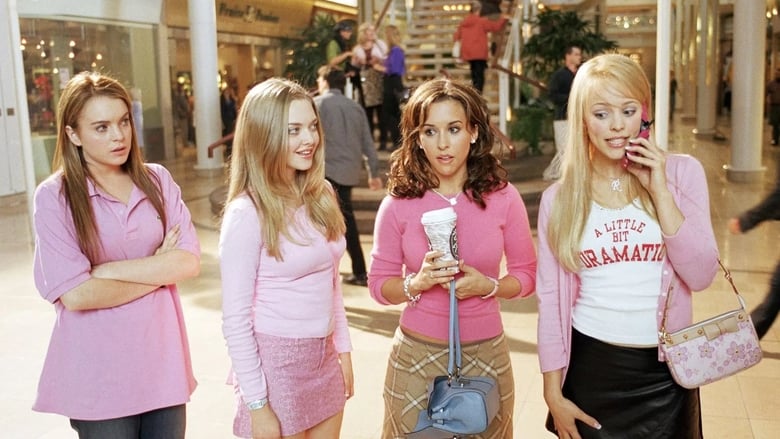

The brilliance of the film’s visual language lies in its deceptive brightness. Waters bathes North Shore High in a saturated, candy-colored palette—a world of fluorescent pinks, baby blues, and perfectly manicured surfaces. This aesthetic choice is a deliberate counterpoint to the narrative's psychological violence. By framing the ruthless social machinations of "The Plastics" within the visual vernacular of a pop music video, the film emphasizes the terrifying dissonance between appearance and reality. The "Burn Book," a tome of scribbled hate, feels all the more venomous because it exists within such a meticulously polished environment.

At the center of this ecosystem is Rachel McAdams’ Regina George, a villain for the ages. McAdams plays Regina not with the mustache-twirling glee of a cartoon antagonist, but with the terrifying, quiet confidence of a dictator who knows her power is absolute. She doesn't need to raise her voice; a mere glance or a withheld compliment is enough to destabilize the social order. The film’s defining metaphor—comparing high school cliques to the animal kingdom of the African savanna—is employed literally through Cady Heron’s (Lindsay Lohan) hallucinations. These feral, chaotic visualizations serve to remind the audience that despite the designer clothes and rigid cafeteria geography, these characters are driven by the same Darwinian impulses as the lions Cady left behind in Africa.

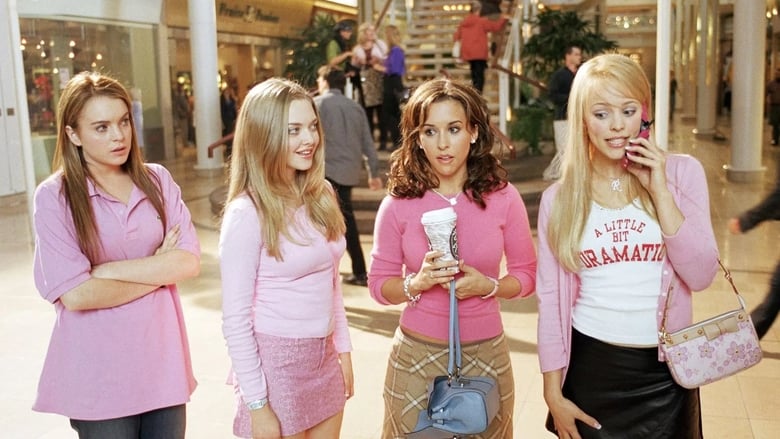

The tragedy of *Mean Girls*, and its emotional core, is the corruption of Cady Heron. The film avoids the lazy trope of the "good girl" defeating the "bad girl." Instead, it charts a far more uncomfortable trajectory: assimilation. To dismantle the regime, Cady must adopt its methods, eventually becoming a more effective tyrant than Regina ever was. The script sharply observes that "Girl World" is a distinct geopolitical entity with its own laws of physics. When Cady breaks the rules—wearing the wrong color, speaking to the wrong ex-boyfriend—the punishment is swift and total isolation. This isn't just bullying; it is a systematic erasure of identity.

Ultimately, *Mean Girls* endures because it refuses to condescend to its subjects. It treats the politics of the junior class with the gravity of a senate hearing. It acknowledges that for a sixteen-year-old girl, the difference between eating lunch at a table and eating in a bathroom stall is not a trivial inconvenience—it is a matter of existential worth. By wrapping this harrowing truth in sharp satire and quotable dialogue, Fey and Waters created a piece of cinema that exposes the savagery lurking beneath the surface of civilized society.