✦ AI-generated review

The Quiet Ache of a Bedtime Story

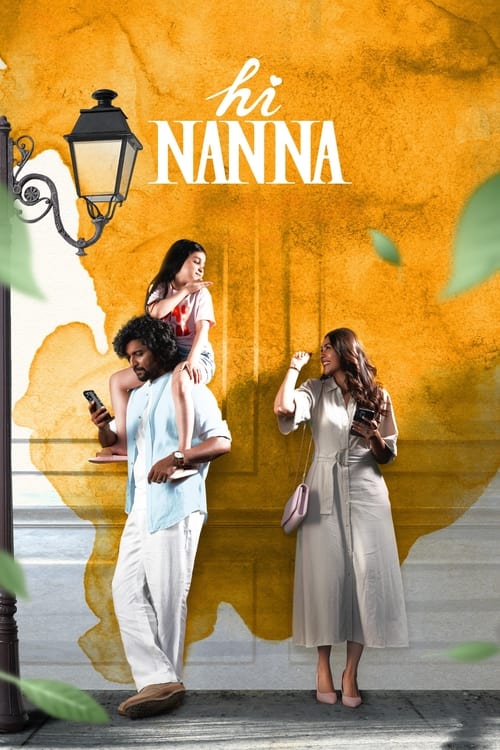

In an era of Indian cinema currently dominated by hyper-masculine spectacles and ear-shattering action sequences, debut director Shouryuv’s *Hi Nanna* arrives like a soft exhale. It is a film that dares to be gentle. While it operates within the familiar architecture of the commercial melodrama—complete with glossy production design and serendipitous encounters—it refuses to let the noise of the genre drown out the whisper of its characters. This is not a film about saving the world; it is about the terrifying, mundane heroism of saving a child’s innocence while your own heart is breaking.

Shouryuv, stepping into the director’s chair for the first time, displays a visual maturity that belies his experience. Assisted by Sanu John Varghese’s cinematography, the film treats Mumbai and Coonoor not merely as locations, but as emotional soundscapes. The frames are painted in cool blues and warm ambers, creating a "protective bubble" aesthetic. Viraj’s (Nani) home looks less like a bachelor pad and more like a fortress of solitude designed to shield his daughter, Mahi, from the harsh realities of her condition—cystic fibrosis, poignantly referred to as "65 Roses." The visual language reinforces the film’s central narrative device: the bedtime story. The flashbacks are shot with a hazy, fairytale quality, blurring the line between the father’s sanitized version of the past and the jagged edges of the truth.

At the center of this emotional storm is Nani, an actor who has mastered the art of the "accessible everyman." As Viraj, he sheds the vanity often associated with leading men. He does not play the single father as a martyr, but as a man exhausted by the weight of his own silence. There is a specific scene involving a photo album—devoid of dialogue—where Nani communicates years of grief merely through the slumping of his shoulders. It is a masterclass in restraint. He is matched by Mrunal Thakur (Yashna), who is tasked with a high-wire act of performance. She must navigate a character who is simultaneously a stranger and an intimate ghost. The chemistry between them is not built on sparks, but on a palpable, shared ache—a sense of recognition that predates their on-screen meeting.

The film is not without its stumbles. The narrative occasionally leans too heavily on convenient coincidences, and the second half threatens to drag under the weight of its own melodrama. However, the film saves itself through its empathetic treatment of the child, Mahi (Baby Kiara). In a genre where child actors are often reduced to cloying plot devices, Mahi is written with agency and wit. Her relationship with the dog, Pluto, and her father feels lived-in and messy, grounding the film’s more ethereal romantic elements.

Ultimately, *Hi Nanna* is a sophisticated exploration of memory and trauma. It asks a difficult question: Do we have the right to curate the past to protect the ones we love? Shouryuv suggests that while truth is inevitable, love is the cushion that softens the blow. It is a polished, heartfelt piece of cinema that proves the loudest emotions are often the ones spoken in a whisper.