✦ AI-generated review

The Symphony of the Vanished

If *Barbarian* (2022) was a film about the terrors lurking in the basement, Zach Cregger’s sophomore effort, *Weapons*, is a treatise on the rot infecting the entire neighborhood. It is a sprawling, chaotic, and relentlessly ambitious "horror epic" that abandons the claustrophobic tension of his debut for something far grander: an American tapestry of grief that feels less like a slasher and more like Paul Thomas Anderson’s *Magnolia* filtered through a fever dream of occult dread.

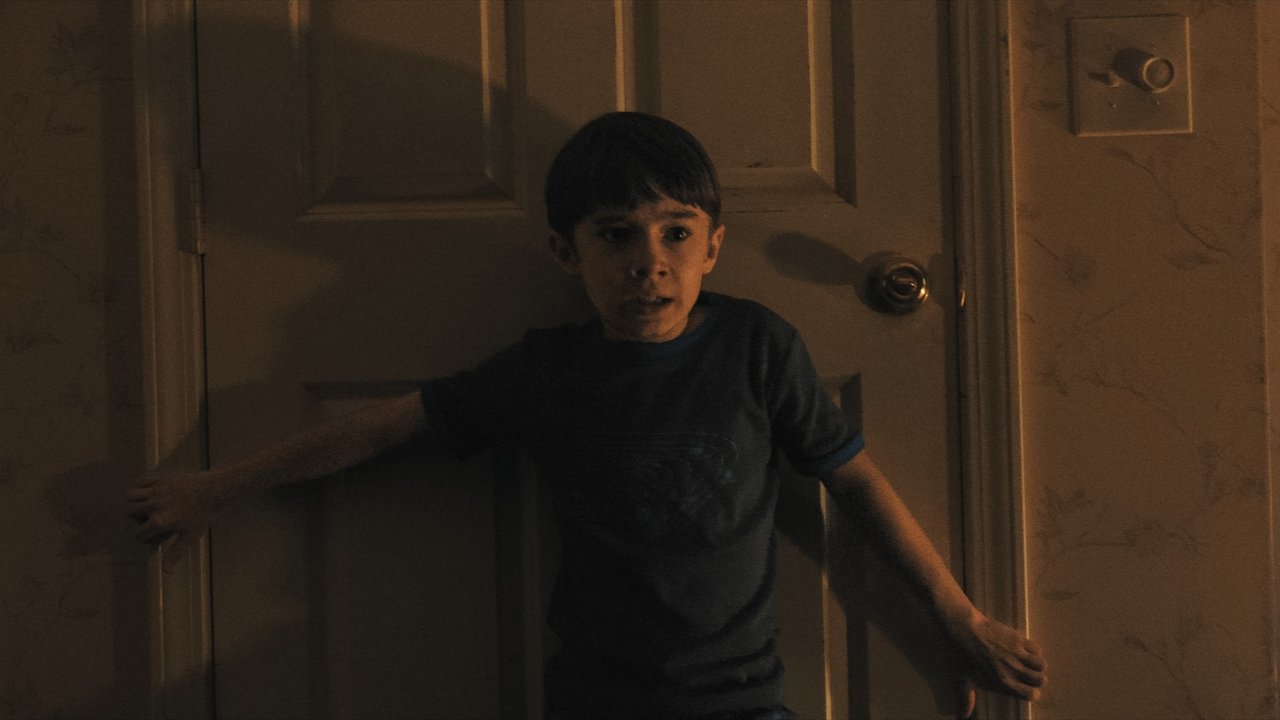

The film’s audacity is established in its opening movement, a sequence destined to be dissected in film schools for years to come. At exactly 2:17 AM, seventeen children in the sleepy town of Maybrook, Pennsylvania, rise from their beds. They do not sleepwalk; they sprint. With arms outstretched like airplanes—or perhaps like crucifixes—they rush into the dark, vanishing into a collective void. It is a sequence of eerie, synchronized beauty that Cregger captures not with the shaky-cam panic of modern horror, but with a sweeping, operatic steadiness. This visual language asserts that the horror here is not an accident; it is a design.

Cregger structures the film as a series of overlapping vignettes, a narrative architecture that allows him to dissect the community left behind. We are introduced to Justine Gandy (Julia Garner), the teacher whose class has disappeared, and Archer Graff (Josh Brolin), a father whose grief has calcified into a dangerous rage. Garner is translucent with anxiety, her performance a masterclass in the disintegration of a psyche under the weight of misplaced suspicion. Brolin, conversely, is a blunt instrument, a man frantically searching for a target.

The genius of *Weapons* lies in its refusal to let the supernatural element overshadow the human failure. While the film eventually peels back its layers to reveal Gladys Lilly (Amy Madigan)—a terrifying, parasitic entity masquerading as a benevolent aunt—the true horror is how the town cannibalizes itself before the witch even reveals her hand. The "weapons" of the title are manifold. They are not just the floating AK-47 that haunts Archer’s nightmares; they are the accusations hurled at Justine, the alcoholism that numbs the pain, and the intergenerational trauma that Gladys feeds upon. The adults in Maybrook are weaponized by their own sorrow, striking out blindly while the children are quite literally consumed by an ancient evil.

Visually, Cregger and cinematographer Larkin Seiple create a world that is brightly lit yet suffocating. The daylight scenes in Maybrook possess a sterile, "uncanny valley" quality, reinforcing the idea that the suburbs are merely a thin veneer over a festering wound. The editing stitches the disparate storylines together with a rhythm that feels musical, building toward a crescendo of violence that is as cathartic as it is devastating.

*Weapons* is not a perfect film; its sheer scope sometimes threatens to collapse under its own weight, and the shift from psychological mystery to creature feature may alienate viewers seeking a tidy resolution. However, its messiness is part of its power. In an era of algorithm-driven cinema, Cregger has delivered a work of distinct, human handwriting. He suggests that the monsters are real, yes, but they are only able to feast because we have already abandoned each other. It is a chilling, thunderous confirmation that Zach Cregger is not just a horror director, but a major American filmmaker.