✦ AI-generated review

The Violent Geometry of Grief

Grief, in its most polite cinematic depictions, is a silent weeping in a rain-streaked window. It is dignified, somber, and quiet. But anyone who has truly mourned knows that grief is actually a vandal. It is loud, rude, and destructive; it rearranges the furniture of your mind and refuses to leave. Dylan Southern’s *The Thing with Feathers*, an ambitious if uneven adaptation of Max Porter’s lyrical novella, understands this violence. However, in translating Porter’s polyphonic prose into a visual medium, Southern has traded the delicate architecture of poetry for the blunt force of a monster movie, resulting in a film that is visually arresting but emotionally claustrophobic.

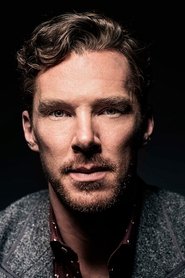

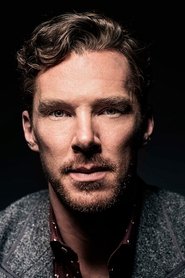

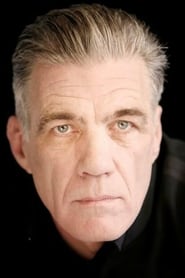

The premise is deceptively simple: a "Sad Dad" (Benedict Cumberbatch) and his two young sons are left reeling in a London flat after the sudden death of their wife and mother. Into this vacuum steps—or rather, crashes—Crow (voiced with gravelly, malicious wit by David Thewlis). In Porter’s text, the father was a scholar obsessed with the poet Ted Hughes, and Crow was a literary manifestation of that obsession—a creature made of ink and words. Southern, perhaps distrusting the cinematic appeal of an academic, reimagines the father as a graphic novelist.

This shift is not merely cosmetic; it fundamentally alters the film’s DNA. By making the protagonist an illustrator, Southern literalizes the metaphor. Crow is no longer a psychological puzzle born of intellectual fixation; he becomes a sketched monster come to life, dragging the film dangerously close to the territory of *The Babadook*. The director, making his narrative feature debut after a career in music documentaries, utilizes a visual language of suffocating darkness. The flat becomes a physical manifestation of the widower’s psyche—inky shadows bleed from the corners, and the clutter of neglect piles up like a barricade against the outside world. It is a striking aesthetic, but one that feels occasionally over-determined, as if the set design is shouting themes the script struggles to whisper.

Benedict Cumberbatch, to his credit, throws his entire physical being into the role. He has always been an actor capable of projecting immense internal pressure, and here he is a coiled spring of exhaustion. He eschews the noble sufferer trope for something sweatier and more frantic. His performance captures the sheer labor of grief—the way the simple act of putting on shoes or making toast becomes a Herculean trial. Yet, because the script strips away the character’s intellectual interiority (the Ted Hughes connection), Cumberbatch is often left with nowhere to go but outward—screaming, scribbling, and contorting. He is fighting a heavy-weight bout against a script that sometimes feels feather-light on subtext.

The film shines brightest in its jagged, surreal interactions between Dad and Crow. David Thewlis provides the film’s chaotic heartbeat, voicing the bird not as a sympathetic counselor, but as a rough, anarchic nanny who bullies the family back to life. These scenes possess a untamed energy that hints at the "wildness" of the source material. However, Southern undermines this by leaning too heavily on the vocabulary of horror—jump scares and creature effects—which suggests a lack of confidence in the drama itself. He treats grief as a spook house rather than a state of being.

Ultimately, *The Thing with Feathers* is a film of powerful fragments that don't quite cohere into a satisfying whole. It admirably refuses to tidy up the messiness of loss, yet it feels trapped by its own literalism. It captures the "Thing"—the monstrous, intrusive presence of death—but it loses the "Feathers"—the lightness, the hope, and the strange, poetic lift that allows us to eventually carry the weight.