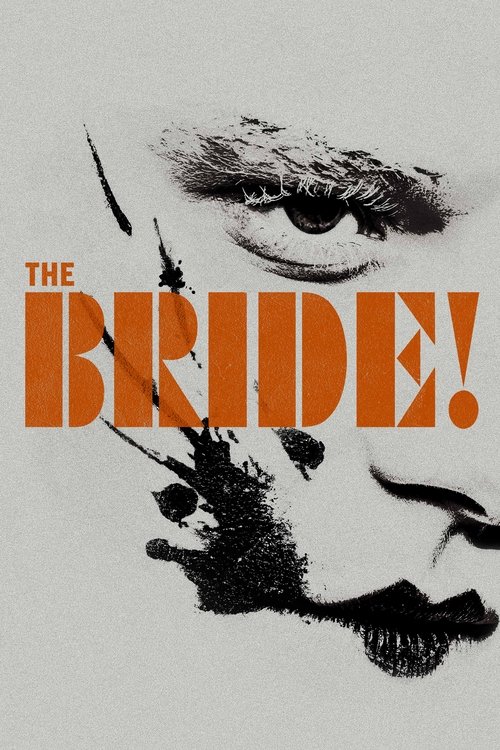

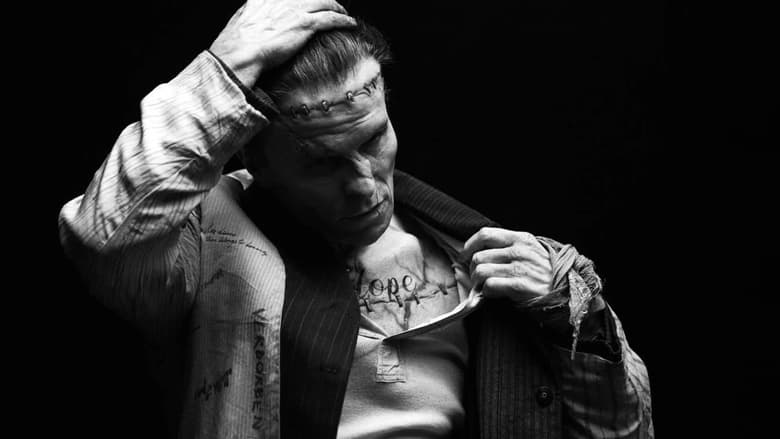

The Scream After the SilenceCinema has spent nearly a century treating the Bride of Frankenstein as an image rather than an entity. In James Whale’s 1935 masterpiece, she is a supreme visual gag—a lightning-struck Nefertiti who hisses, rejects her intended, and is promptly destroyed. She exists for three minutes. She is an object of desire, then an object of horror, but never a subject. In *The Bride!*, Maggie Gyllenhaal does not just resurrect the body; she resurrects the voice. The result is a film that vibrates with a feral, punk-rock energy, transforming a classic monster myth into a jagged exploration of female autonomy and the violent messiness of self-creation.

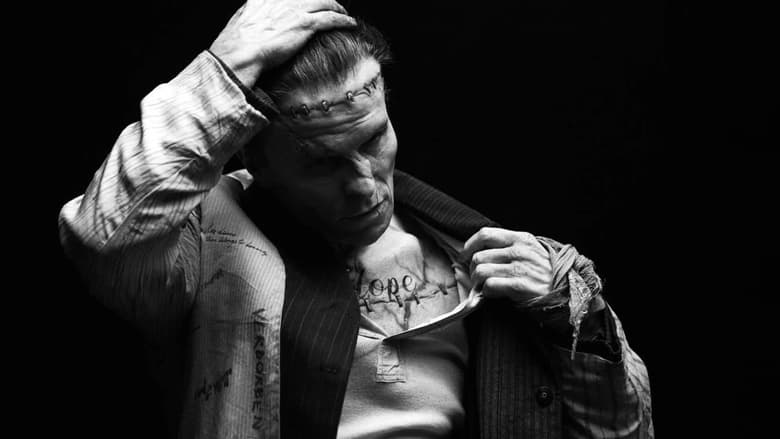

Gyllenhaal’s Chicago of the 1930s is not the sepia-toned nostalgia trap we are used to. It is a suffocating, industrial labyrinth that feels closer to the grime of 1980s New York—a world of soot, steam, and blood. The director, collaborating with cinematographer Lawrence Sher, uses the IMAX format not to widen the horizon, but to entrap us in the terrifying intimacy of resurrection. When the Bride (a ferocious Jessie Buckley) opens her eyes, the camera doesn't observe her; it assaults her, mirroring the sudden, violent influx of consciousness. The "inky tar" that stains her mouth isn't just a makeup choice; it’s visual shorthand for a soul that has been dragged back from the void against its will, leaving a permanent bruise on the vessel.

The narrative spine remains familiar—a lonely Frankenstein (Christian Bale) seeks a mate—but the emotional musculature is entirely new. Bale, delivering a performance of tender, hulking pathos, plays the creature not as a villain, but as a man crushing under the weight of his own isolation. He begs Dr. Euphronious (Annette Bening) for a companion, imagining a domestic fantasy. But creation is an act of chaos, not order. Gyllenhaal argues that you cannot construct a living thing to fit a specific shape in your life. To give life is to give agency, and agency is inherently dangerous to the creator.

This is where Buckley tears the film open. Her Bride is not a blank slate waiting for instruction; she is a woman who died with a lifetime of unsaid words and has returned to scream them all at once. Watching her learn to move, speak, and eventually rebel is like watching a natural disaster in reverse. The chemistry between Buckley and Bale is not romantic in the traditional sense; it is the collision of two volatile elements. The film suggests that their bond isn't forged in lightning, but in their shared status as outcasts—monsters who refuse to be polite about their monstrosity.

The film’s third act dissolves into what can only be described as an anarchic fever dream. As the Bride rejects the "companion" label to forge her own identity, the film sheds its gothic skin to become something more modern and unrestrained. It is a risky tonal shift, one that threatens to derail the narrative momentum, yet it feels emotionally honest. Gyllenhaal seems less interested in the mechanics of a plot and more focused on the texture of liberation—how messy, loud, and inconvenient it truly is.

*The Bride!* is not a perfect film; it is jagged and occasionally overwhelmed by its own ideas. But it is vibrantly, undeniably alive. In an era of sanitized IP management, Gyllenhaal has used the bones of a franchise to build something that feels dangerous again. She has looked at the most famous female monster in history—a woman literally made for a man—and asked the only question that matters: What happens when she decides she belongs to herself?