Shadows in the SunThe buddy-action genre is a crowded room, often echoing with the hollow sounds of corporate chemistry and algorithmic plotting. It is rare to find a film that enters this space not merely to occupy it, but to wrestle with it. *The Wrecking Crew*, directed by Ángel Manuel Soto, arrives on the streaming landscape carrying the baggage of its origin—a viral social media pitch between stars Jason Momoa and Dave Bautista—but quickly sheds the gimmickry of its conception. Soto, whose previous work like *Charm City Kings* and *Blue Beetle* demonstrated a keen eye for marginalized communities, utilizes this vehicle not just for spectacle, but to explore the friction between indigenous authenticity and the corrosive nature of external greed.

Visually, Soto refuses to treat Hawaii as a passive postcard. While the film delivers the requisite pyrotechnics of the genre, the camera lingers on the textures of Oahu that tourists rarely see—the rusted corrugated metal, the humid community halls, and the shadowy corners of development sites where history is paved over. The cinematography creates a tangible sense of place that feels threatened, turning the setting into a central character rather than a green-screen backdrop. When the action erupts, it is heavy and destructive, mirroring the film's thematic concern: the physical and cultural displacement of people. The violence isn't weightless; it breaks things, just as the conspiracy at the film's center threatens to fracture the island’s soul.

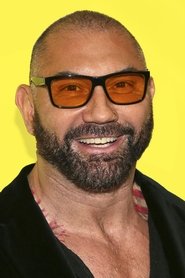

At the narrative's core is the tectonic collision of half-brothers Jonny (Momoa) and James (Bautista). The script wisely inverts the expected casting archetypes. Bautista plays against his "Drax" persona, embodying James with a disciplined, simmering stoicism—a Navy SEAL whose rigidity is a shield against his past. Momoa, conversely, is allowed to be the chaotic element, a loose-cannon cop whose nihilism masks a deep well of grief.

Their reunion, precipitated by their father’s mysterious death, avoids the cloying sentimentality often found in reunion dramas. Instead, their relationship is defined by physical space—how they occupy a room, how they avoid eye contact, and how they fight in tandem. The "wrecking" in the title applies as much to their emotional barriers as it does to the scenery. There is a genuine pathos in watching these two physically imposing men struggle to articulate the pain of abandonment, finding a common language only through the unraveling of the conspiracy that killed their father.

Ultimately, *The Wrecking Crew* succeeds because it respects its audience enough to layer its adrenaline with conscience. It is a film that understands the allure of the "tough guy" mythos but questions the cost of that toughness on the family unit. Soto has crafted a picture that operates effectively as a genre exercise while smuggling in a poignant critique of gentrification and legacy. It suggests that while you can wreck a building or a car, the bonds of blood and the history of a land are far more resilient, and far more dangerous to ignore.