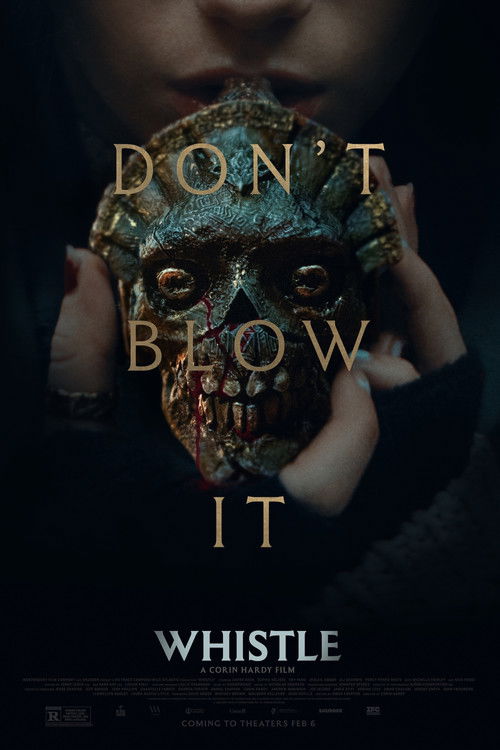

The Sound of Coming UndoneHorror cinema has long understood that the ear is more vulnerable than the eye. We can close our eyes to shut out a monster, but we cannot close our ears to a scream. In Corin Hardy’s *Whistle* (2026), this biological vulnerability becomes the narrative engine. By centering the terror on a specific, historical auditory artifact—the Aztec Death Whistle—Hardy moves beyond the tired "cursed object" tropes of recent years and delivers a film that feels less like a slasher and more like a sonic assault on the inevitability of fate.

Hardy, a director who proved his aptitude for atmospheric dread in *The Hallow* and his flair for gothic iconography in *The Nun*, here strips away the religious pomp for something more guttural. The premise is deceptively simple: a group of high school outsiders, led by the jagged, trauma-hardened Chrys (Dafne Keen), stumble upon the titular whistle. To blow it is to summon not a demon, but one's own future death. It is a concept that borrows the linear dread of *It Follows* and the fatalism of *Final Destination*, yet Hardy directs it with a texture that feels uniquely tactile.

Visually, the film is a feast of autumn shadows and practical effects. Where modern horror often retreats into the sterility of digital monsters, *Whistle* insists on the physical. The "future deaths" that hunt the teenagers are grotesque distortions of the self—charred flesh, broken bones, waterlogged skin—rendered with a practical, prosthetic weight that makes them sickeningly real. When a character who is destined to burn sees their future self, still smoking and screaming, lurching toward them in a high school hallway, the horror is existential. It is the literal manifestation of the anxiety that plagues this generation: the fear that the future is not a promise, but a threat hunting you down.

However, the film’s true pulse lies in its performances, specifically the chemistry between Keen and Sophie Nélisse, who plays Ellie. The script, adapted from Owen Egerton’s short story, could easily have left them as archetypes—the Loner and the Good Girl. Instead, Keen and Nélisse imbue their developing relationship with a desperate, tender gravity. Their connection grounds the supernatural chaos. We care about their survival not because the script demands it, but because their shared vulnerability feels authentic. Keen, in particular, carries the film with a ferocious intensity; she is an exposed nerve, reacting to the supernatural intrusion with a rage that mirrors her internal grief.

The sound design deserves its own billing. The whistle’s cry—a sound historically described as the scream of a thousand corpses—is utilized here to bone-chilling effect. It cuts through the film’s quieter moments, serving as a reminder that the timeline has been breached. Hardy understands that the anticipation of the sound is often worse than the sound itself, and he orchestrates the silence as masterfully as the chaos.

If *Whistle* stumbles, it is perhaps in its third act, where the mechanics of the curse require a level of exposition that momentarily slows the momentum. Yet, it recovers for a finale that feels both inevitable and earned. In an era where horror often feels manufactured for viral clips, *Whistle* stands out by focusing on the ancient terror of simply being heard. It suggests that some sounds, once released, can never be silenced, and that the only thing scarier than a ghost is the version of yourself that didn’t survive.