The Acoustics of HellThe modern apartment complex is a peculiar purgatory: a honeycomb of concrete where we are stacked efficiently upon one another, separated by mere inches of floor and ceiling, yet miles apart in spirit. In South Korea, the phenomenon of *cheung-gan-so-eum* (inter-floor noise) is not merely a nuisance; it is a recognized social crisis that frequently escalates into violence. Director Kim Soo-jin’s debut feature, *Noise*, takes this very real, very mundane anxiety and amplifies it until it cracks the plaster. It is a film that understands that the most terrifying sound isn't a demon’s roar, but the rhythmic, unexplained thud of a neighbor who may or may not exist.

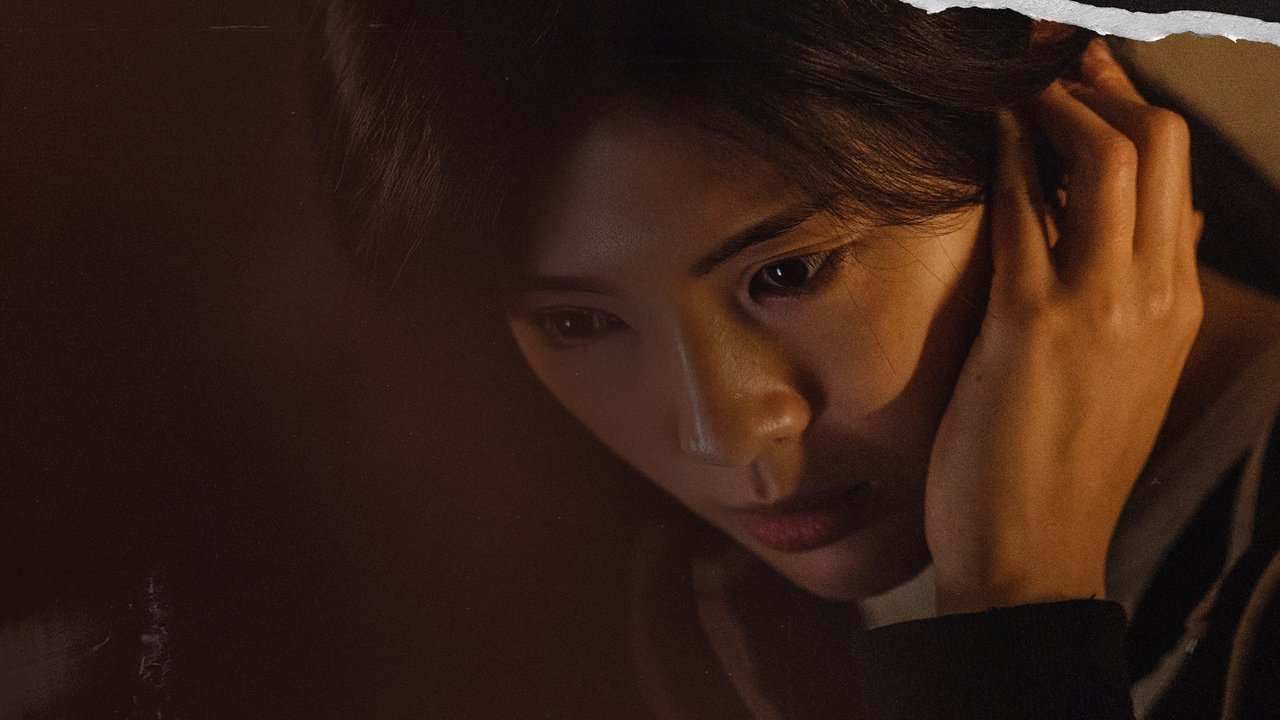

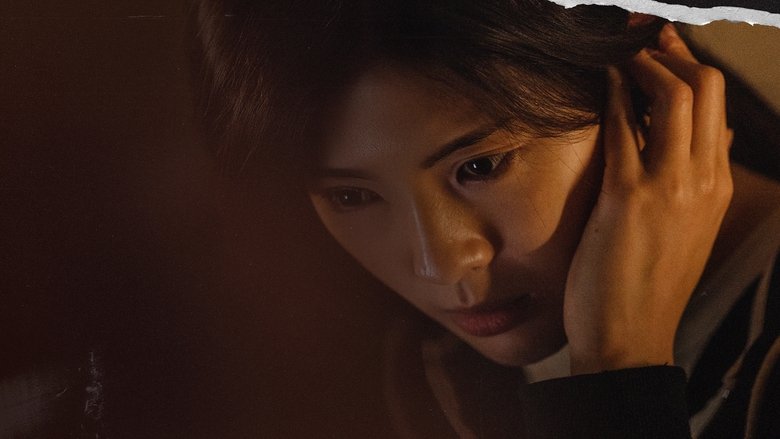

Kim’s approach to the genre is refreshingly sensory. While the visual language of the film captures the sickly, fluorescent-lit pallor of a decaying building awaiting reconstruction, the true protagonist—and antagonist—is the sound design. We follow Joo-young (Lee Sun-bin), a young woman with a hearing impairment, searching for her missing sister in a building that seems to be vibrating with malice. By centering on a deaf protagonist, Kim pulls off a brilliant inversion of the "haunted house" trope. We are not just waiting for jump scares; we are placed in a suffocating bubble of silence that is frequently punctured by the visual evidence of noise we cannot hear, or conversely, by the terrifying, amplified feedback of a hearing aid picking up frequencies that shouldn't be there.

The film’s most chilling mechanic involves Joo-young’s speech-to-text app. In scenes of unbearable tension, she watches her phone screen as it transcribes voices from an empty room. It is a modern séance, a technological Ouija board that translates the supernatural into cold, glowing text. This device serves as a potent metaphor for the film’s central conflict: the failure of communication. Joo-young is isolated not just by her disability, but by a society that refuses to listen. The police are dismissive, the neighbors are hostile, and the building’s committee is more concerned with property values than human life. The horror here is bureaucratic indifference as much as it is spectral vengeance.

However, *Noise* struggles to maintain this elegant dread in its final act. As the mystery unravels and the basement’s secrets are exhumed, the film trades its psychological nuance for more conventional genre mechanics. The ghostly presence, once a terrifying abstraction representing urban rage, becomes a literal entity that can be run from and fought. It is a common stumble in high-concept horror; the explanation rarely satisfies the curiosity sparked by the unknown. Yet, Lee Sun-bin’s performance anchors the chaos. Her portrayal of Joo-young avoids the trap of saintly victimhood; she is angry, capable, and driven by a fierce, terrified love for her sister.

Ultimately, *Noise* is a striking debut that resonates because it taps into a universal urban fear. It suggests that our homes are not sanctuaries, but resonant chambers where the traumas of the past echo endlessly through the pipes. It asks us to consider what we are really hearing when the floorboards creak above us: is it just the settling of the building, or is it the sound of a city that has forgotten how to care for its living?