✦ AI-generated review

The Myth in the Mud

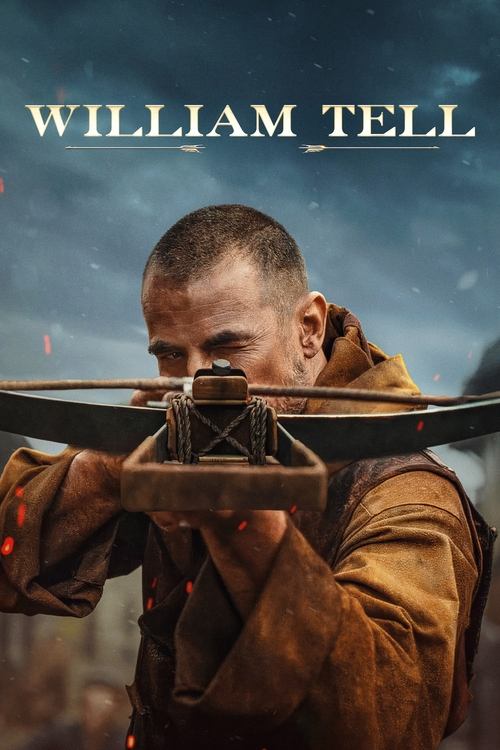

There is a distinct, heavy weariness that permeates modern historical epics—a determination to strip away the romance of legend and replace it with the gray slurry of "reality." We no longer allow our folk heroes to simply be heroes; they must be traumatized veterans, reluctant saviors, and grim-faced introverts. Nick Hamm’s *William Tell* (2025) is the latest casualty of this trend, a film that takes Friedrich Schiller’s rousing 1804 play and drags it through the mud of the 14th century, hoping that dirt equals depth. While it aims for the visceral gravitas of *Braveheart*, it lands somewhere closer to a confused, albeit handsome, history lesson that cannot decide if it is an anti-war meditation or a franchise-launching blockbuster.

Visually, Hamm and cinematographer Jamie D. Ramsay have crafted a film of undeniable scale. The Swiss Alps (doubled by Italy) loom with majestic indifference over the petty squabbles of men, providing a breathtaking canvas for the bloodshed. Yet, the director’s visual language often feels at war with itself. On one hand, we have the "mud and blood" aesthetic—limbs are severed with *Game of Thrones* enthusiasm, and Claes Bang’s face is perpetually smeared with the grime of the oppressed. On the other, we have stylistic anachronisms that border on camp, such as the camera mounting a ride-along on a crossbow bolt—a "video game" shot that jolts the viewer out of the purported realism. Similarly, Connor Swindells’ villainous Gessler is costumed in armor that reviewers have rightly noted looks closer to "techno-fetish gear" than medieval steel. These visual clashes suggest a film that doesn't trust the inherent power of its setting, feeling the need to spice up the Middle Ages with modern adrenaline.

At the heart of this storm stands Claes Bang, an actor of immense physical presence and soulful reserve. His William Tell is not the swaggering marksman of lore but a Crusades veteran haunted by PTSD, a man who has "seen enough death." Bang does his best to anchor the film with a stoic, simmering rage, treating the crossbow not as a tool of glory but as a burden. The script attempts to modernize the legend by giving Tell a Muslim wife, Suna (Golshifteh Farahani), a narrative choice clearly designed to inject contemporary resonance and diversity into a Eurocentric myth. While Farahani is a magnetic performer, her character—and the film’s broader attempt to be a "modern morality tale"—often feels suffocated by the plot’s mechanical need to move from one action set piece to the next. The film wants to be an exploration of the cost of violence, yet it clearly revels in the spectacle of it.

The film's centerpiece—the legendary apple shot—is executed with undeniable tension. Hamm wisely slows the pace here, allowing the political terror of the moment to breathe. It is a sequence that reminds us why this story has endured for seven centuries: it is the ultimate confrontation between absolute tyranny and individual skill. However, the emotional impact of this scene is diluted by the film’s clumsy third act, which seems less interested in resolving the thematic conflict than in setting up a sequel. By the time the credits roll, the narrative arc feels incomplete, sacrificed on the altar of "universe building."

*William Tell* is not a failure of craft, but of conviction. It possesses the components of a great epic—a commanding lead, a hateable villain, and a timeless struggle—but it lacks the courage to simply tell its story without glancing over its shoulder at modern blockbuster expectations. It hits the target, certainly, but it misses the bullseye.