✦ AI-generated review

The Optimist’s Dilemma

There is a specific frequency at which James L. Brooks films operate—a hum of neurotic humanism that defined the emotional landscape of American cinema in the 1980s. In masterpieces like *Broadcast News* and *Terms of Endearment*, Brooks harmonized professional ambition with personal disaster, creating a world where the stakes of a newsroom edit felt as life-altering as a terminal diagnosis. In *Ella McCay*, his first feature in fifteen years, that frequency returns, but it rings with the eerie, hollow echo of a ghost station. The film is not merely a period piece because it is set in 2008; it feels like a relic because it insists on a version of political reality that perhaps never existed at all.

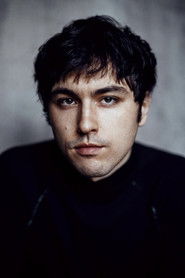

To watch *Ella McCay* is to witness a collision between a director’s steadfast worldview and a modern audience’s hardened carapace. Brooks places us in the shoes of the titular Ella (Emma Mackey), a young, idealistic Lieutenant Governor thrust into the top job. The setting of 2008 is a deliberate, if baffling, choice. By rewinding the clock to the pre-Trump, pre-social media saturation era, Brooks attempts to clear the board of modern toxicity to focus on "pure" human foibles. However, the result is disorienting. The central conflict—a "scandal" involving Ella’s husband (Jack Lowden) and a minor misappropriation of state property—feels almost charmingly quaint. In an age where political norms are shattered daily, watching a protagonist hyperventilate over a moral infraction that wouldn't make the ticker on today's cable news creates a narrative dissonance that the film never quite resolves.

Visually, the film retains Brooks's signature "messiness," favoring mid-shots of actors talking over one another in crowded rooms. At his best, this technique creates a suffocating sense of reality; here, it occasionally feels like a stage play struggling to find its cinematic footing. Yet, there are glimmers of the old magic in the dialogue. Brooks still writes people who are smarter than they are wise, characters who can articulate their neuroses but cannot stop tripping over them. There is a specific rhythm to the way Ella and her mentor, the outgoing Governor (played with acerbic delight by Albert Brooks), trade barbs—a reminder of a time when movie characters were allowed to be hyper-verbal without being ironic.

The film’s emotional anchor, however, is not the politics, but the patriarchy. Beneath the capital building maneuverings lies a wounded daughter story. Emma Mackey does heroic work grounding Ella, playing her not as a saint, but as a woman exhausted by the effort of maintaining her own goodness. Her scenes with Woody Harrelson, who plays her estranged, philandering father, contain the film's only true danger. Harrelson is slippery and unrepentant, a chaos agent in Ella’s carefully curated life. When Ella traces the definition of "trauma" in a dictionary—a scene that teeters on the edge of being too literal—Mackey sells the moment with a fragility that transcends the script's clumsiness. It is here, in the messy, unfixable terrain of family, that Brooks finally seems at home.

Ultimately, *Ella McCay* is a film out of time. It is a work of aggressive decency released into a cynical world. It posits that shame is still a powerful political currency and that good intentions are a valid form of governance. While the narrative often collapses under its own wistful ambition, there is something poignantly brave in its failure. Brooks has returned not to conquer modern cinema, but to remind it of a softer, slower language it has long since forgotten how to speak.