The Uncanny Valley of the DollsTo watch Keenen Ivory Wayans’ *White Chicks* (2004) two decades after its release is to stare into a funhouse mirror that has somehow, against all odds, become a crystal ball. Upon its arrival, the film was largely dismissed by the critical establishment as a grotesque exercise in lowbrow humor—a "drag" movie in every sense of the word. Yet, time has been kind to the Wayans brothers. What was once viewed as a crude prosthetic gag has curdled into a surprisingly sharp sociological artifact, a fever dream that captured the precise moment when American celebrity culture began to consume itself.

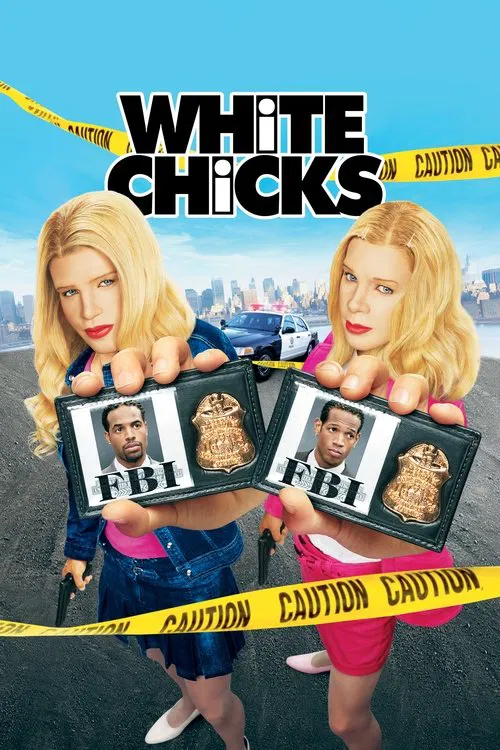

The premise is deceptively simple, bordering on the absurdities of a *Looney Tunes* short. FBI agents Kevin and Marcus Copeland (Shawn and Marlon Wayans), desperate to salvage their careers after a botched drug bust, go undercover as the Wilson sisters—two vapid, high-society heiresses clearly modeled after the Hilton dynasty. But to treat this transformation purely as a plot device is to miss the film’s visual audacity. The makeup effects, often criticized for their terrifying unreality, are actually the film’s most potent weapon. The Copelands do not look like human women; they look like manufactured dolls, possessing a plasticine sheen that mirrors the artificiality of the world they are infiltrating. The Wayans are not aiming for the convincing realism of *Mrs. Doubtfire*; they are inhabiting the grotesque, unintentional horror of early 2000s beauty standards.

By navigating the Hamptons in "whiteface," the film engages in a complex act of reverse-minstrelsy. It does not mock white women so much as it mocks the *performance* of white femininity—the vocal fry, the performative fragility, and the entitlement that shields the wealthy from consequence. The directors use the genre of the buddy-cop comedy to smuggle in a critique of privilege that is both blunt and strangely nuance. When Marcus and Kevin move through this spaces, they are invisible not because their disguise is perfect, but because the society around them is too self-absorbed to look closely at "the help" or even their own peers.

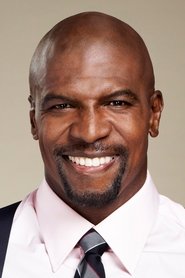

The film’s beating heart, however, is found not in its satire of whiteness, but in its surprising exploration of black masculinity through the character of Latrell Spencer, played with kinetic brilliance by Terry Crews. In a film about disguises, Latrell is the only character who is unapologetically himself. The now-iconic scene where he joyfully belts out Vanessa Carlton’s "A Thousand Miles" reclaims a pop cultural artifact that "shouldn't" belong to him. It is a moment of pure, transcendent joy that breaks the binary the film sets up. Latrell desires the illusion (the white disguise), but his energy is so undeniable that he effectively shatters the movie’s racial barriers by sheer force of personality.

Ultimately, *White Chicks* endures because it refuses to be polite. It is a loud, chaotic, and often messy collision of race, class, and gender that feels more honest about the American experience than many prestige dramas of its era. It suggests that identity in the modern age is not something we are born with, but something we put on—like a layers of latex or a designer dress—to survive a world that is constantly trying to define us. It is not a perfect film, but it is a fearless one, willing to be ugly in order to show us exactly what we look like.