✦ AI-generated review

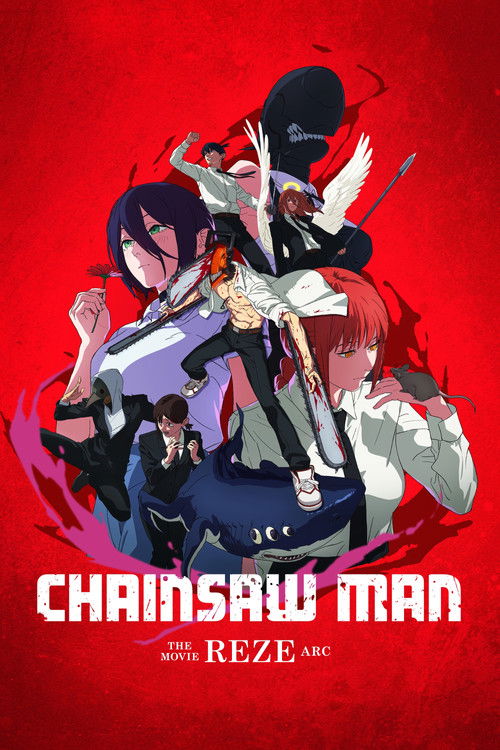

The Gunpowder Heart

In the vast, screaming machinery of modern shonen anime, protagonists usually dream of becoming kings, hokages, or the very best. Denji, the ragged heart of *Chainsaw Man*, dreams of toast with jam and a girl who might hold his hand without trying to kill him. *Chainsaw Man - The Movie: Reze Arc*, directed by Tatsuya Yoshihara, takes this pathetic, deeply human desire and weaponizes it. This is not merely an action spectacle or a bridge between television seasons; it is a tragedy of ballistics, exploring how two people engineered for destruction attempt, briefly and disastrously, to build something soft.

Yoshihara, stepping into the director’s chair after serving as action director for the series' debut, brings a kinetic, almost feverish energy to the screen. Where the television series occasionally held its audience at a cinematic distance, Yoshihara collapses the space between the viewer and the violence. The animation here is tactile—you feel the rain that soaks Denji and Reze in the phone booth; you feel the humidity of the night air. But the film’s most striking visual language is not found in the gore (though there is plenty), but in the silence. The lighting shifts from the sterile fluorescence of Public Safety offices to the warm, amber glow of the café where Reze works, creating a visual sanctuary that we, like Denji, desperately want to believe is real.

The narrative pivots on the fable of the Town Mouse and the Country Mouse, a motif that Reze introduces as a playful question but which festers into an existential indictment. Do you choose the safety of a quiet life where you starve, or the danger of a rich life where you might be eaten? Denji, who has known only starvation, cannot comprehend why anyone would choose the quiet. Reze, a Soviet super-soldier molded into a "Bomb Girl," understands the lethal cost of the city all too well.

The film’s emotional centerpiece—a midnight swimming lesson in a school pool—is a masterclass in this duality. Stripped of their devil-hunting uniforms and societal roles, swimming in the dark water, they are just two teenagers suspended in a moment of stolen time. It is a scene of suffocating intimacy. Yoshihara frames them against the vastness of the night sky, making them look small, fragile, and doomed. We watch Denji fall in love not with a grand gesture, but with the terrifying realization that he is being seen, really seen, for the first time.

Of course, the tragedy of *Chainsaw Man* is that intimacy is almost always a prelude to amputation. When the truth detonates—quite literally—the transition from romance to horror is seamless because, in Denji’s world, they are the same thing. Reze is not a villain in the traditional sense; she is a mirror. Like Denji, she is a tool of the state, a weapon disguised as a person. Her manipulation of him is cruel, but her final attempt to return to the café—to choose the "Country Mouse" life, to choose Denji over the mission—is the film’s most devastating wound.

The *Reze Arc* ultimately argues that in a world governed by control—be it Makima’s cold bureaucracy or the Gun Devil’s terror—the most radical act of rebellion is to love someone who cannot save you. The film leaves us not with the triumph of a hero, but with the image of a boy waiting with flowers that will never be delivered, learning that the most painful cuts don't come from chainsaws, but from the silence of an empty doorway.