The Bacon of Existence: A study in PinkIt is a mistake to view *Peppa Pig* merely as a pacifier for the pre-verbal masses. To dismiss the work of Neville Astley and Mark Baker as digital babysitting is to ignore one of the most rigorously consistent, if terrifyingly absolute, universes in modern visual storytelling. Emerging in 2004, this British animated series did not just enter the crowded marketplace of children's television; it flattened it, quite literally, into a two-dimensional plane of primary colors and unyielding social contracts. If cinema is a mirror held up to nature, *Peppa Pig* is a mirror held up to the id of a four-year-old—fractured, ego-centric, and occasionally profound.

The visual language of the series is its most striking, and perhaps most misunderstood, asset. In an era where animation aggressively chases hyper-realism (the anxious fur textures of Pixar, the atmospheric lighting of *Bluey*), *Peppa Pig* retreats into a radical, almost Brechtian minimalism. The world is rendered in flat, unshaded vector graphics. A hill is a green semi-circle; a house is a child’s hieroglyph of domesticity. This is not laziness; it is an aesthetic manifesto. By stripping away depth, the creators force us to focus entirely on the social hierarchy of the Pig family. There are no shadows in Peppa’s world to hide in—only the blinding light of social expectation and the inevitable failure to meet it.

At the center of this flatland stands Peppa herself, a protagonist who rejects the cloying sweetness of her American counterparts. She is not a "good" child in the Disneyfied sense; she is a realist. She is bossy, vain, and prone to fat-shaming her father with a casual cruelty that borders on the operatic. Yet, there is a refreshing honesty to her tyranny. When she hangs up the phone on her best friend Suzy Sheep because Suzy can whistle and she cannot, we are witnessing a moment of raw, unadulterated human jealousy. It is a scene of emotional violence that Scorsese would recognize, played out in the key of C Major.

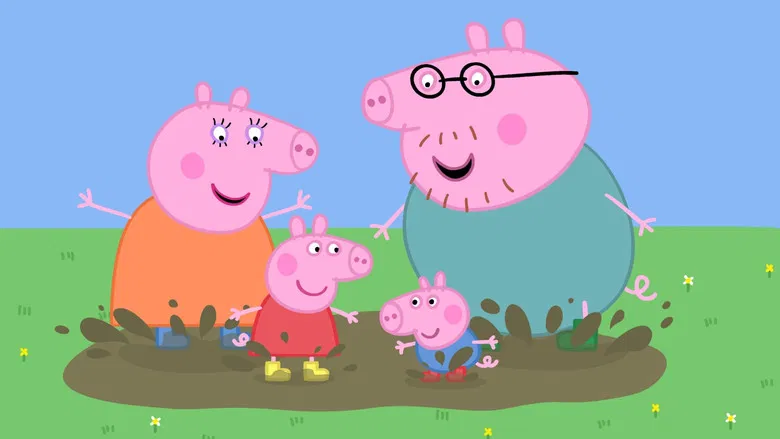

The recurring motif of "muddy puddles" serves as the series' central metaphor. On the surface, it represents innocent play. But observe the ritual: the boots must be worn; the mud must be jumped in; the collapse into laughter must be communal. It is a cleansing ritual, a momentary descent into the filth of existence before returning to the sanitized order of the house on the hill. The fall is essential. Everyone falls—even the Queen. In this universe, gravity is the great equalizer, and mud is the great unifier.

However, the show's true emotional weight—if one can call it that—rests on the shoulders of Daddy Pig. Here is a patriarch trapped in a Sisyphian cycle of incompetence and ridicule. He is an expert on everything, yet master of nothing. He claims to be a structural engineer, yet cannot hang a picture frame without destroying the living room wall. And yet, he endures. His resilience in the face of his family's constant mockery ("Silly Daddy") is the show's hidden tragedy. He is the modern man: overconfident, undervalued, and perpetually stuck in a slide at the playground, his physical form too large for the plastic tube of life.

Ultimately, *Peppa Pig* is a comedy of manners that rivals Jane Austen in its observance of social friction. It captures the rigid polite society of the British middle class—the thank-you letters, the jumble sales, the unspoken tensions at the playgroup—and exposes the absurdity underneath. It is a world where every animal species is segregated by sound yet united by language, a surreal ecosystem where a potato can be a celebrity and a rabbit can hold seventeen different jobs simultaneously.

In its refusal to moralize, *Peppa Pig* achieves a kind of Zen purity. It does not ask us to be better; it only asks us to jump. And as the characters collapse on their backs, legs kicking at the void, laughing at the sheer absurdity of being alive, one cannot help but feel that they know something we do not.