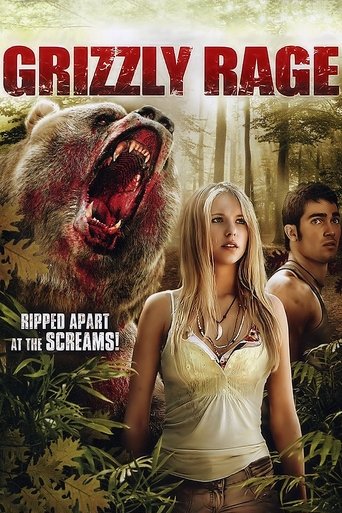

The End of InnocenceIn the summer of 1967, America was preoccupied with the "Summer of Love," a cultural phenomenon that preached harmony, connection, and a return to the garden. But in the high altitudes of Montana’s Glacier National Park, nature was preparing a brutal rebuttal. Burke Doeren’s *Grizzly Night* is not merely a creature feature; it is a cinematic eulogy for the illusion of safety. By dramatizing the "Night of the Grizzlies"—the infamous August evening when two separate bears killed two young women miles apart—Doeren has crafted a film that feels less like a horror movie and more like a historical demarcation line. Before this night, the wilderness was a playground; after it, the woods had teeth again.

Doeren, making his feature directorial debut, brings a cinematographer’s eye to the proceedings. The visual language of *Grizzly Night* is suffocatingly beautiful. The camera lingers on the vast, indifferent majesty of the mountains, often framing the human characters as insignificant specks against an ancient backdrop. This is not the glossy, high-contrast look of modern slashers; the lighting is naturalistic, relying on the murky amber of campfires and the harsh, unforgiving beams of period-appropriate flashlights. The director understands that the true terror isn't the bear itself—which is used sparingly, maintaining a *Jaws*-like mystique—but the darkness that surrounds it. The audio landscape is equally precise; the snap of a twig or the heavy, wet breathing of an unseen animal carries more weight than any jump scare could.

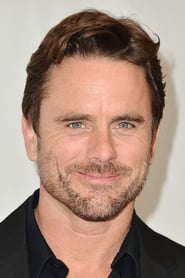

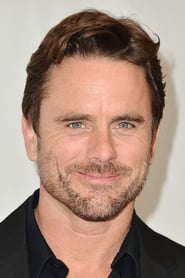

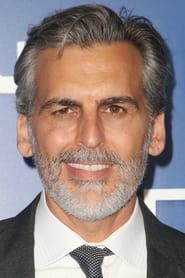

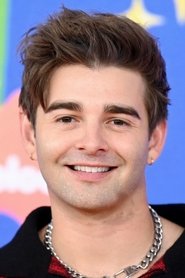

At the narrative’s core is a struggle against hubris. The film meticulously reconstructs the park’s pre-tragedy atmosphere, where rangers and campers alike treated grizzlies as roadside attractions rather than apex predators. The casting of Charles Esten and Oded Fehr provides a necessary gravitas, but it is the younger cast members, portraying the doomed campers, who carry the emotional burden. The script does not treat them as "body count" fodder but as tragic figures of a naive era. The split narrative structure—tracking two separate attacks nine miles apart—is a risky choice that threatens to fracture the tension. However, Doeren uses it to emphasize the sheer, chaotic randomness of the event. There is no villain here, no supernatural evil—only an ecosystem reasserting its dominance.

Ultimately, *Grizzly Night* transcends the limitations of the "eco-horror" genre. It refuses to turn the bears into monsters; they are simply animals behaving according to their nature in a world that humans foolishly thought they had tamed. The film is a tense, often heartbreaking reminder of our own fragility. While it occasionally stumbles under the weight of its dual storylines, the cumulative effect is a chilling realization: we are guests in the wild, and hospitality is not guaranteed. Doeren has delivered a film that respects the tragedy of 1967 while ensuring that the growl in the dark still haunts the audience long after the credits roll.