The Breath of RevolutionHistory has a way of calcifying art. We look back at the French New Wave—that seismic shift in 1960s cinema—and see it as an inevitability, a deliberate intellectual movement chiseled into marble by giants like Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut. But in *Nouvelle Vague*, Richard Linklater gently smashes that marble to reveal the anxiety, the improvisation, and the messy humanity that actually fueled the revolution. Linklater, a director who has spent his career obsessed with the passage of time (*Boyhood*, the *Before* trilogy), here turns his gaze to a specific, suspended moment: the terrifying, exhilarating weeks when *Breathless* was just a low-budget disaster waiting to happen.

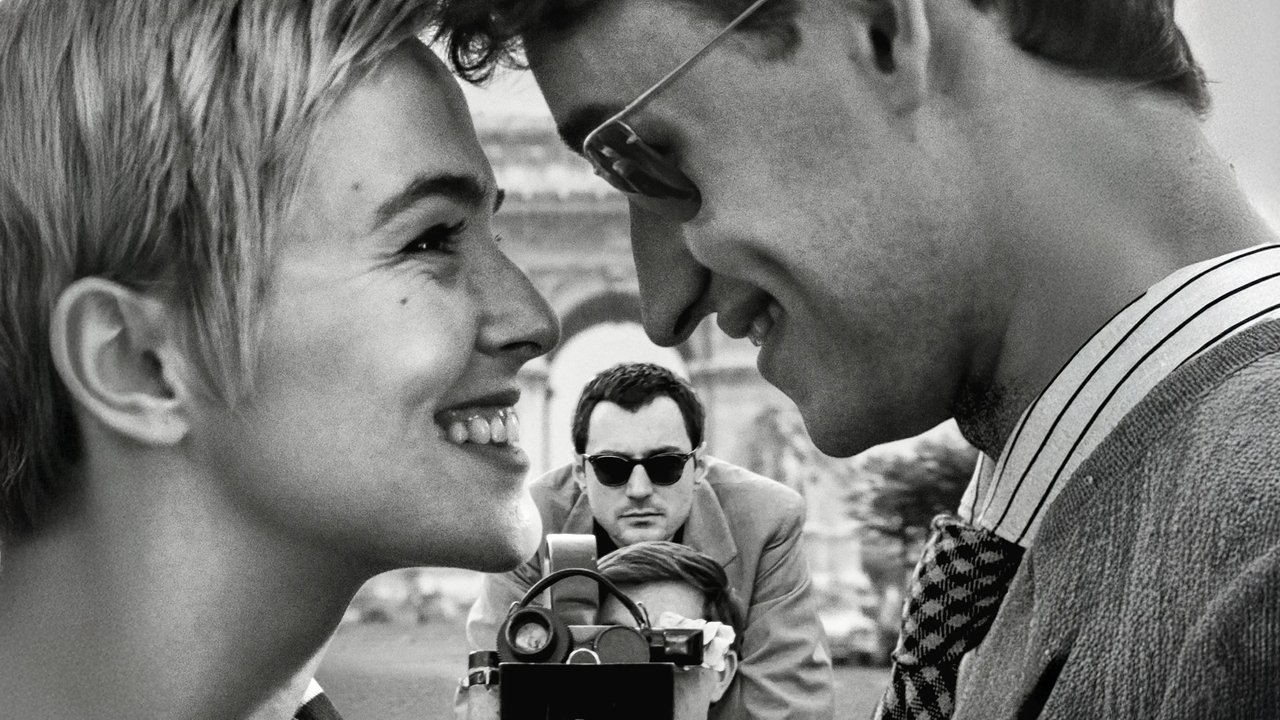

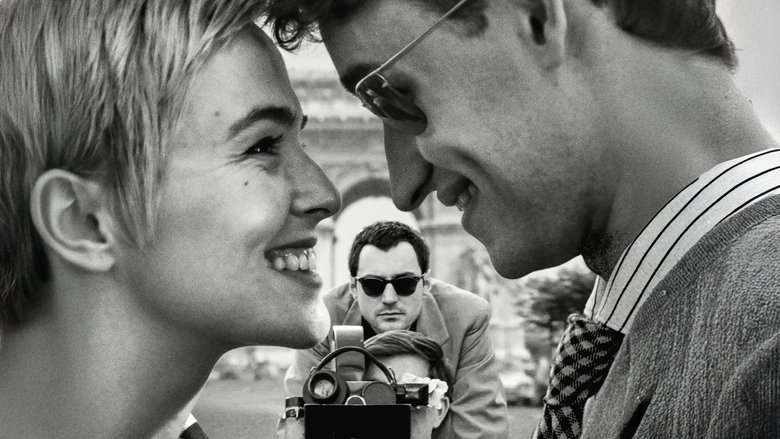

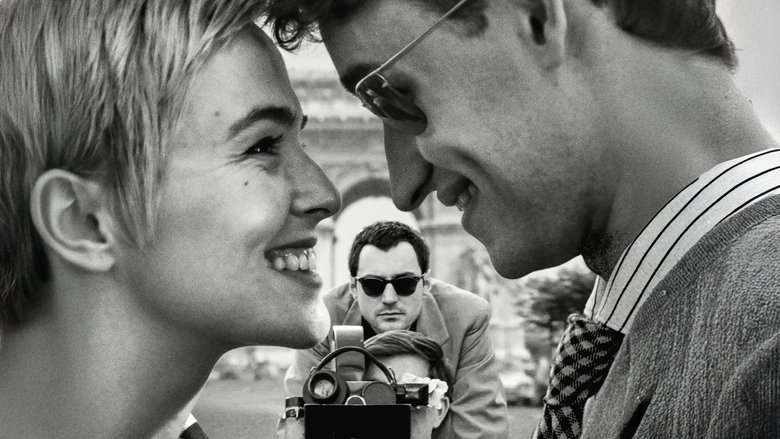

Shot in stark black-and-white and trapped within the claustrophobic Academy ratio, the film does not merely reference the aesthetic of 1959; it inhabits it. Linklater avoids the trap of the glossy biopic where famous faces parade through well-lit sets. Instead, the camera feels jittery and alive, mirroring the guerrilla filmmaking tactics Godard famously employed. We are placed on the Champs-Élysées, dodging pedestrians and stealing shots without permits, feeling the illicit thrill of cinema being stripped of its polish. When Linklater introduces the titans of the era—Truffaut, Chabrol, Rohmer—he does so with static, almost mugshot-like portraits, a playful cataloging of the conspirators who were about to burn down the establishment.

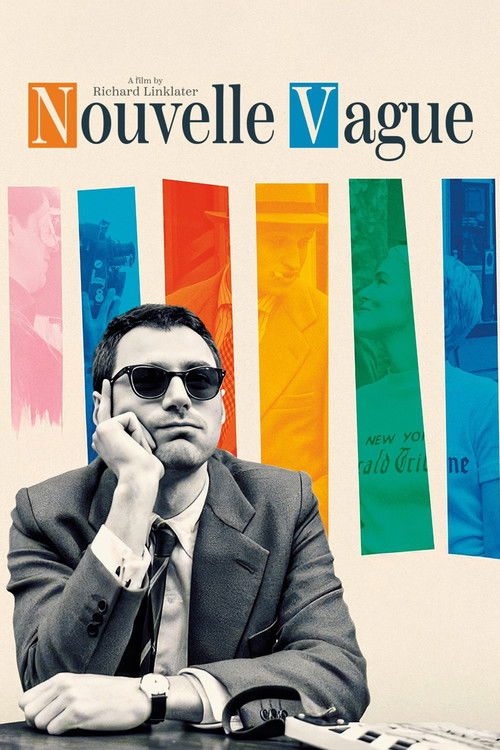

However, the film’s true resonance lies not in its historical reenactment, but in its study of the collision between method and madness. At the center is the friction between Guillaume Marbeck’s Godard and Zoey Deutch’s Jean Seberg. Marbeck plays the director not as a sage, but as an inscrutable paradox—hidden behind dark glasses, fueled by an unearned confidence that borders on arrogance. He is a man inventing a language he doesn't quite speak yet.

Opposite him, Deutch delivers a performance of heartbreaking vulnerability. As Seberg, the Hollywood starlet dropped into this Parisian experiment, she represents the traditional order being dismantled. She isn't witnessing a revolution; she is enduring a chaotic lack of direction, fearing for her career, unaware that her confusion is exactly the texture Godard is mining. The film brilliantly recontextualizes her iconic performance in *Breathless* not as cool detachment, but as the exhaustion of an actor trying to find footing on shifting sand.

Ultimately, *Nouvelle Vague* is a conversation between two eras of independent spirit. Linklater, the patron saint of American "slacker" cinema, recognizes a kindred spirit in the young Godard—not in style, perhaps, but in the ethos of making do with what you have. The film suggests that the "cool" of the New Wave wasn't a pose, but a byproduct of necessity and panic. By stripping away the mythology, Linklater gives us something far more valuable: the reminder that cinema is a high-wire act, performed without a net, where the fear of falling is the only thing that makes us fly.