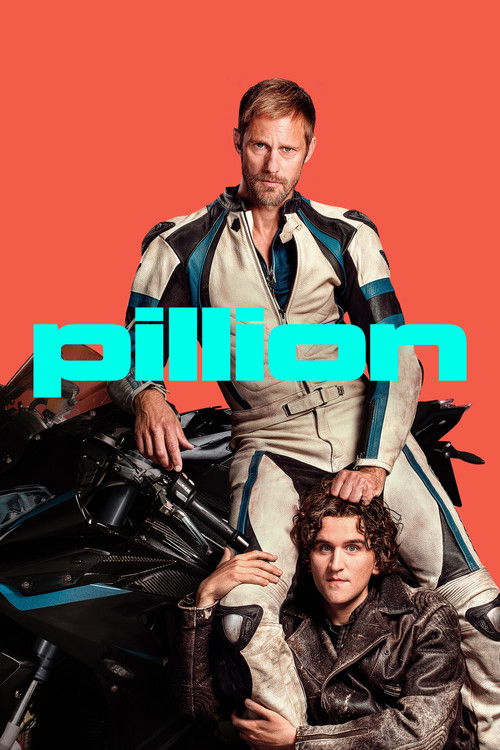

The Architecture of SubmissionTo categorize Harry Lighton’s feature debut *Pillion* merely as a "kink drama" or, even more reductively, a "gay romance," is to miss the peculiar, tender alchemy at its core. Cinema has long struggled with the depiction of BDSM, frequently relegating it to the realm of the thriller or the punchline, viewing it through a lens of pathology. Lighton, adapting Adam Mars-Jones’s novella *Box Hill*, takes a different, far more humanistic route. He suggests that submission is not always a subtraction of the self; occasionally, it is the only way a person can find the necessary structure to grow.

The film’s visual language is built on a study of textures. We begin in the suffocating beige of suburban Bromley, where Colin (a transfixing Harry Melling) lives a life defined by soft edges—fluffy sweaters, barbershop quartets, and the passive aggression of British politeness. Lighton captures this world with a static, almost stifling frame, emphasizing the inertia of Colin’s existence. When Ray (Alexander Skarsgård) enters the frame, he brings with him the stark, absorbing black of leather and the chrome of his motorcycle. The contrast is not subtle, but it is effective: Ray is not just a love interest; he is a heavy, gravitational object that warps the space around him, pulling Colin out of his beige stupor.

The central metaphor of the title—the "pillion" being the passenger seat on a motorcycle—serves as the film's philosophical spine. To ride pillion is to surrender control of the destination while trusting the driver with your life. Melling’s performance is a masterclass in physical micro-acting. We watch him transform from a man who seems apologetic for his own existence into someone who finds a strange, rigid dignity in obedience. The scene where Ray shaves Colin’s head is not played for shock value, but as a baptism. As the hair falls, the "soft" Colin is stripped away, revealing a sharper, albeit more vulnerable, visage. It is a ritual of ownership, yes, but Lighton frames it with an intimacy that borders on the sacred.

However, *Pillion* avoids the trap of romanticizing the imbalance of power entirely. Skarsgård plays Ray with a stony, almost opaque charisma that is initially alluring but slowly reveals its own limitations. He is a man who needs control to function, a fragility masked by dominance. The film’s brilliance lies in how it shifts our empathy. Initially, we fear for Colin’s safety, but as the narrative unfolds, we realize Colin is the one undergoing a metamorphosis, while Ray remains static, trapped in his own rules. The sexual encounters, explicit and unvarnished, are treated as conversations—dialogues of need and boundary-testing that are far more honest than the polite dinner table chatter Colin leaves behind.

Ultimately, *Pillion* is a coming-of-age story wrapped in leather. It argues that we sometimes need to lose ourselves in someone else's script before we can write our own. Lighton has crafted a film that is often surprisingly funny—the absurdity of domesticating a biker fantasy is never lost on him—but leaves a lingering ache. It respects the mystery of what draws people together, acknowledging that the things that liberate us might look like chains to the outside world. It is a confident, tactile debut that understands that the passenger seat offers a view of the road that the driver can never see.