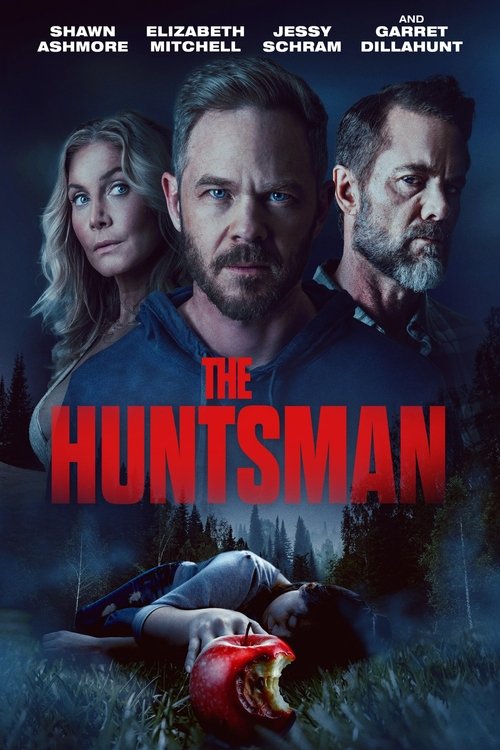

The Anatomy of a Quiet ObsessionIn the modern thriller landscape, silence is often treated as a void to be filled—usually by exposition, jump scares, or a Hans Zimmer-esque wall of sound. But in *The Huntsman* (2026), silence is a weapon. Director Kyle Kauwika Harris, an indigenous filmmaker who has previously explored the rugged desolation of the American West in *Out of Exile* and *Reverence*, here trades the open plains for the claustrophobic sterility of an ICU and a sun-bleached Oklahoma town. The result is a film that feels less like a whodunit and more like a slow-acting poison, seeping into the veins of its characters until the toxicity is indistinguishable from love.

Harris’s direction is surgically precise, rejecting the frenetic pacing of standard procedural dramas. He favors static shots that linger just a second too long, forcing the audience to sit in the discomfort of a gaze. The cinematography washes the screen in clinical whites and overexposed yellows, creating a visual language where nothing can hide, yet everything is obscured. It is a world where the blinding light of the Southwest sun doesn’t clarify the truth; it bleaches it out, leaving behind only the jagged edges of morality.

The narrative anchor is Max Mason (Shawn Ashmore), an ICU nurse whose professional empathy has curdled into a pathological need to be near the broken. Ashmore, shedding his blockbuster hero skin, delivers a performance of terrifying repression. His stillness is loud. When he volunteers to care for Lincoln Raider (Garret Dillahunt)—a comatose man accused of the ritualistic "Huntsman" murders—the film ostensibly sets up a cat-and-mouse dynamic. But Harris subverts this immediately. Lincoln is not a Hannibal Lecter figure taunting from a cell; he is a void, a sleeping body upon which Max, the town, and the audience project their fears and desires.

The central tension arises not from the question of "Did he do it?" but from the terrifying intimacy that develops between the accuser and the accused. The scenes within the Raider home are masterclasses in atmospheric dread. Elizabeth Mitchell, playing Lincoln’s fiercely protective wife Jolene, brings a brittle, tragic dignity to the role. She and Ashmore circle each other like wounded animals, their dialogue sparse but laden with the unspoken. Harris understands that the true horror isn't the serial killer trope of hearts in boxes (though the Snow White motif is utilized with grim elegance); the horror is the malleability of truth when viewed through the lens of trauma.

Critically, *The Huntsman* falters slightly in its third act, where the demands of the genre force a resolution that feels too tidy for the messy psychological unraveling that preceded it. The introduction of Detective Darby (Jessy Schram) provides necessary narrative momentum but occasionally punctures the film’s hypnotic trance with police procedural mechanics that feel pedestrian compared to the psychodrama occurring in the Raider house.

However, the film recovers in its final moments, returning to the ambiguity that serves as its greatest strength. Dillahunt, an actor capable of shifting from affable to menacing with a mere twitch of the jaw, anchors the climax with a performance that refuses to give the audience easy answers. The "conversation" around this film will likely center on its refusal to villainize or canonize its subjects. Harris forces us to ask: Is the desire to save a monster any less pathological than the desire to be one?

Ultimately, *The Huntsman* is a study in the violence of care. It suggests that empathy, unchecked, can become a form of possession. While it may not rewrite the rules of the thriller genre, it refines them, stripping away the noise to reveal the terrifying quiet at the heart of human obsession. It is a film that doesn't just ask you to watch; it asks you to wait, and in that waiting, you might find yourself holding your breath.