The Last Song Before the Curtain FallsThere is a specific kind of silence that follows a revolution—not the noise of the change itself, but the quiet realization of the person who has been left behind. In Richard Linklater’s *Blue Moon*, that silence is deafening, even when drowned out by the clinking glasses and overlapping chatter of Sardi’s restaurant. Set on the rainy night of March 31, 1943, the film captures the precise moment American musical theater pivoted from the witty cynicism of Lorenz Hart to the earnest optimism of Rodgers & Hammerstein. But this is not a history lesson; it is a ghost story about a man who is still alive, haunting the edges of his own obsolescence.

Linklater has always been a master of time, usually treating it as a fluid, gentle river in works like the *Before* trilogy or *Boyhood*. Here, time is a claustrophobic cage. The film unfolds in near real-time, confined almost entirely to the plush, smoky interiors of Sardi’s. Cinematographer Shane F. Kelly shoots the restaurant not as a bustling hub of Broadway glamour, but as a purgatory for the displaced. The warm, tungsten glow of the lamps feels less inviting and more feverish, trapping the characters in a golden amber. We are stuck in this booth with Lorenz Hart (Ethan Hawke), and as the night wears on, the walls seem to close in, mirroring the lyricist’s shrinking relevance in a world that is rapidly deciding it prefers corn-fed sentimentality to his urban sophistication.

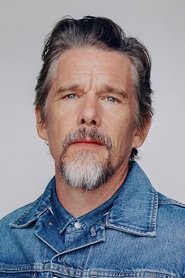

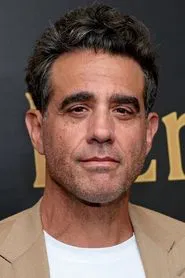

At the center of this chamber piece is Ethan Hawke, delivering a performance of such jagged, frantic vulnerability that it hurts to watch. Hawke’s Hart is a "whirling dervish of charm and pain," a man who uses words as both a shield and a shiv. He is small, sweating, and disintegrating before our eyes. He holds court at the bar, badgering the patient bartender (Bobby Cannavale) and terrified of the inevitable arrival of his former partner, Richard Rodgers (Andrew Scott).

The tragedy of Hawke’s performance lies in his awareness. Hart knows *Oklahoma!* is a masterpiece. He knows the exclamation point in the title—which he mocks relentlessly—signals a new sincerity he cannot replicate. When he describes the "cheesily upbeat" cowboys of the new show, it’s not just jealousy; it’s the despair of a sophisticate who realizes the world has stopped laughing at his jokes.

The film’s emotional anchor—and perhaps its most controversial element—is Hart’s relationship with Elizabeth (Margaret Qualley), a young admirer who represents the connection he desperately craves but cannot maintain. Their interactions are painful symphonies of deflection. Hart, a closeted gay man in the 1940s, projects a complex, impossible desire onto her, trying to rewrite his own narrative into one of conventional romance. Qualley plays Elizabeth with a "heedless girlishness" that eventually gives way to pity, and the scene where Hart’s facade finally cracks in her presence is shattering. It creates a portrait of a man who is "out of time" not just artistically, but romantically and existentially.

*Blue Moon* is not an easy watch. It lacks the breezy philosophical meandering of *Waking Life* or the sun-dappled nostalgia of *Dazed and Confused*. Instead, it offers a harsh, fluorescent look at the cost of genius. Linklater suggests that cultural shifts don't just happen in headlines; they happen in quiet rooms where one man realizes his song is over. As the dawn approaches and the patrons of the *Oklahoma!* premiere flood the bar, bringing with them the future of Broadway, Hart is left adrift. It is a devastating tribute to the messy, brilliant, and broken human beings who pave the way for perfection, only to be swept aside by it.