The Anatomy of DevotionIf *Violation*—Madeleine Sims-Fewer and Dusty Mancinelli’s razor-wire debut—was a scream of feminine rage, their sophomore feature *Honey Bunch* is a nervous giggle that slowly curdles into a choke. Where their previous film dismantled the rape-revenge genre with brutal efficiency, here they turn their gaze toward the institution of marriage, dissecting the terrifying proximity between "unconditional love" and total erasure. This is not a film about monsters under the bed; it is about the monster holding your hand, whispering that everything is going to be okay.

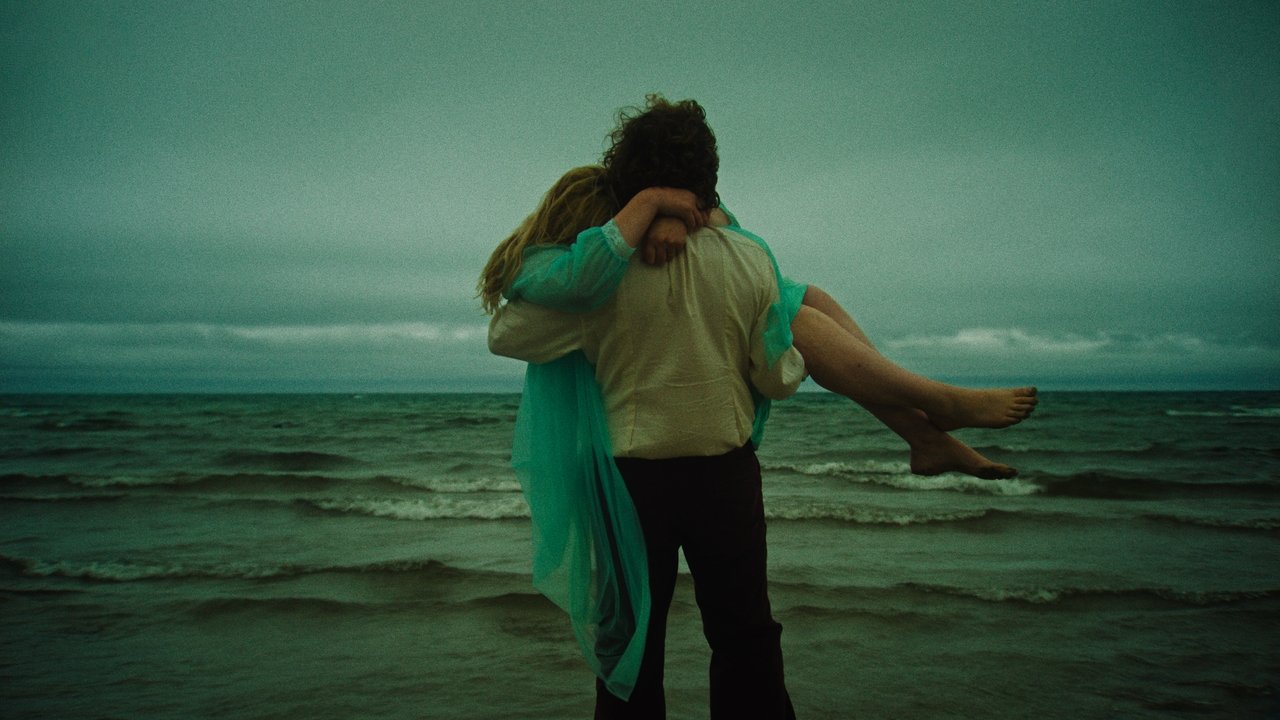

From the opening frames, Sims-Fewer and Mancinelli establish a visual language that is disorienting by design. The film is drenched in a 1970s aesthetic—not the fun, disco-hued 70s, but the beige, sickly 70s of *Don’t Look Now* or *Images*. The cinematography utilizes aggressive crash zooms and a soft, vaseline-smeared lens that makes every frame feel like a memory dissolving in real-time. We are trapped in the perspective of Diana (Grace Glowicki), a woman whose brain is recovering from a car accident she cannot recall. The facility where her husband Homer (Ben Petrie) has taken her is less a hospital and more a Gothic mausoleum of bad vibes, run by a wonderfully severe Kate Dickie. The environment itself feels medicated—hazy, sluggish, and fundamentally untrustworthy.

The casting here is the film’s most potent special effect. Glowicki and Petrie are partners in real life, a fact that lends an uncomfortable texture to their on-screen dynamic. There is a lived-in shorthand to their bickering and affection that makes the subsequent gaslighting feel nauseatingly intimate. Petrie plays Homer not as a mustache-twirling villain, but as a "nice guy" whose devotion is suffocating. He loves Diana so much he wants to fix her, even if "fixing" her means sanding away the parts of her that are inconvenient. Glowicki is a revelation, her performance oscillating between slapstick confusion and guttural body horror. She physicalizes the trauma of memory loss—the way she moves through the facility is jerky and uncertain, like a puppet whose strings are being pulled by someone just out of frame.

The film’s descent into body horror is gradual, then sudden. The "treatment" Diana undergoes involves flashing lights, vile dietary restrictions, and a creeping sense that her body is no longer her own. The directors use these genre tropes to interrogate the concept of the "perfect wife." As Diana’s memories return, they clash violently with the narrative Homer has constructed for her. The horror lies in the realization that for some men, a partner is only an extension of their own ego—a honey bunch to be molded, preserved, and consumed. The subplot involving Jason Isaacs as a desperate father to another patient (India Brown) mirrors this theme, suggesting that this toxic stewardship is not an anomaly, but a systemic rot.

*Honey Bunch* may frustrate those looking for a traditional jump-scare fest. Its pacing is deliberate, and its tone shifts wildly from absurdist comedy to grotesque tragedy. But this instability is the point. It captures the vertigo of a failing relationship, where you can’t tell if you’re crazy or if the person you love is driving you there. Sims-Fewer and Mancinelli have crafted a film that asks us how much of ourselves we are willing to amputate to keep a relationship alive. The answer, they suggest, is terrified silence.