The Architecture of DoubtPaolo Sorrentino has spent much of his career orchestrating the carnival. From the disco-thumping decadence of *The Great Beauty* to the grotesque pageantry of *Loro*, he has been the ringmaster of Italian excess. But in *La Grazia*, the music stops. The confetti is swept away, leaving only the cavernous, echoing halls of the Quirinale Palace and a man sitting alone in the dark. It is a startling pivot—a "white semester" not just for its protagonist, but for the director himself. Here, Sorrentino trades the sacred profane for the profane sacred, delivering a meditation on power that is less about wielding it than crumbling under its weight.

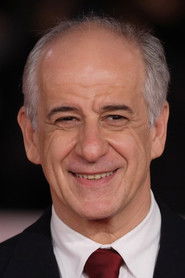

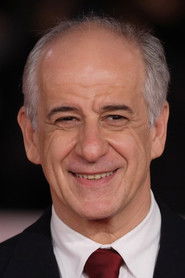

The film reunites Sorrentino with his eternal muse, Toni Servillo, marking their seventh collaboration. Yet, this is not the Servillo of *Il Divo*, where he played Giulio Andreotti as a rigid, vampiric gargoyle. Here, as the fictional President Mariano De Santis, Servillo is a study in crumbling masonry. Nicknamed "Reinforced Concrete" for his judicial rigidity, De Santis is six months away from the end of his term. He is a man who has spent a lifetime interpreting the law, only to find that the law has no language for the messiness of the human heart.

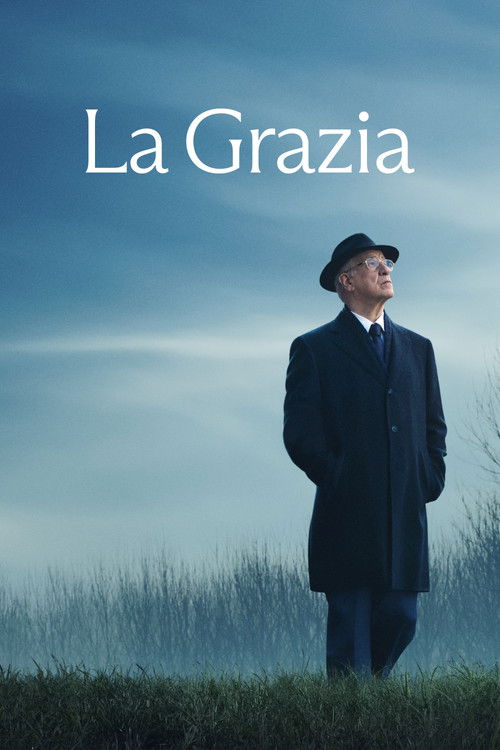

Sorrentino’s visual language in *La Grazia* is strikingly austere, often described by critics as "Rembrandtian." He traps his characters in pools of shadow, surrounded by the oppressive weight of history—busts, tapestries, and gold leaf that seem to mock the transience of the flesh. The camera rarely swoops; it lingers. It watches De Santis eat quinoa in silence; it watches him stare at a dying horse named Elvis in the palace stables. These moments of stillness create a suffocating atmosphere where the silence is louder than any of Sorrentino’s usual techno beats.

However, Sorrentino cannot entirely suppress his surrealist instincts, and thank goodness for that. The film’s most talked-about sequence—the arrival of the Portuguese President during a storm—is a masterclass in the absurdity of protocol. As the wind flips the red carpet and rain lashes the dignitary, the honor guard remains frozen, and a techno track begins to pulse. It is a hilarious, terrifying tableau of a system so paralyzed by rules that it cannot perform a simple act of human kindness. It is the film’s thesis in miniature: we have built structures to order the world, but the storm is coming anyway.

At its core, *La Grazia* is a tragedy about the impossibility of moral purity. De Santis is faced with three decisions that will define his legacy: a euthanasia bill and two pardon requests for murderers. His daughter and confidante, Dorotea (played with piercing intelligence by Anna Ferzetti), urges him toward progress, but De Santis is paralyzed. He is a Catholic and a widower, haunted by the memory of a wife whose fidelity he doubts even in death. The film suggests that "grace"—the title’s double meaning of a pardon and divine favor—is not something a President grants, but something he desperately seeks for himself.

This is a film that asks, "Who owns our days?" as the clock ticks down on a presidency and a life. By stripping away the parties and the plastic surgeries that populate his other films, Sorrentino has found something rawer and more resonant. *La Grazia* does not offer the catharsis of a great speech or a political victory. Instead, it offers a shot of an astronaut on a video call, floating in the void, as isolated as the President in his palace. It is a profound work of art that argues that in the end, whether we are rulers or prisoners, we all face the dark alone.