The Gospel of Second ChancesThe modern romantic comedy often struggles to find its footing between cynicism and fantasy. We live in an era where love is frequently gamified by apps or dissected by therapy-speak, leaving the genre to wonder: is romance a feeling, or is it a skill to be mastered? In Linda Mendoza’s *Relationship Goals* (2026), this question is not merely subtext; it is the text itself. Adapted from Pastor Michael Todd’s bestselling guide on spiritual courtship, the film attempts a curious alchemy, trying to fuse the didactic nature of a self-help sermon with the fizzy effervescence of a workplace rivalry. The result is a film that occasionally buckles under the weight of its own message, yet manages to stay afloat thanks to the buoyant, undeniable magnetism of its leads.

Mendoza, a veteran director with a sharp eye for comedic timing honed on television sets like *30 Rock* and *Grown-ish*, frames New York City not as a gritty urban sprawl, but as a glossy arena of ambition. The setting—a high-stakes morning television show—provides a frantic, high-contrast backdrop for our protagonist, Leah Caldwell (Kelly Rowland). Mendoza shoots the newsroom with a kinetic, polished energy, emphasizing the "glass ceiling" pressure that Leah faces. However, the visual language sometimes betrays the film’s commercial roots; the lighting is often too flat, too bright, lending the proceedings a sitcom-like sheen that reminds us we are watching a parable rather than a slice of life.

The narrative friction arrives in the form of Jarrett Roy (Method Man), Leah’s ex-boyfriend and new professional rival. The script positions them as classic screwball antagonists: she is the disciplined, Type-A producer; he is the charismatic chaotic element. But the twist here is Jarrett’s weapon of choice: a literal copy of the book *Relationship Goals*, which he claims has reformed his "bad boy" ways.

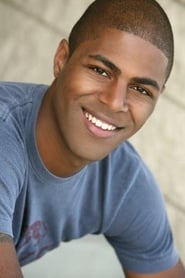

This is where the film navigates its most treacherous waters. Integrating a real-world self-help book into the diegesis of a film risks turning art into an infomercial. There are moments where the dialogue feels less like organic conversation and more like a citation from the source material. Yet, despite the occasional didactic stiffness, the film finds its emotional truth in the performers. Method Man, transitioning seamlessly into the role of a romantic lead, brings a rugged vulnerability to Jarrett. He plays the character not as a man who has "found the answers," but as one who is genuinely, perhaps desperately, trying to apply them.

The heart of the film, however, beats in the silence between the dialogue. Rowland and Method Man possess a lived-in chemistry that cannot be manufactured. When the script stops preaching and allows them to simply *be*—to look at each other with the weary, guarded hope of two people who know each other's scars—the film transcends its genre trappings. Rowland, in particular, excels at portraying the internal war of the modern professional woman: the fear that softening one's heart is a betrayal of one's ambition.

Ultimately, *Relationship Goals* is a fascinating artifact of our time—a movie that suggests love requires study and spiritual intentionality as much as it requires sparks. While the narrative sometimes feels prescriptive, treating romance as a problem to be solved with the right handbook, the sheer charisma of its stars provides the necessary grace notes. It is a film that preaches to the choir, certainly, but thanks to Mendoza’s steady hand and the luminous presence of her cast, even the skeptics might find themselves humming along to the hymn.