✦ AI-generated review

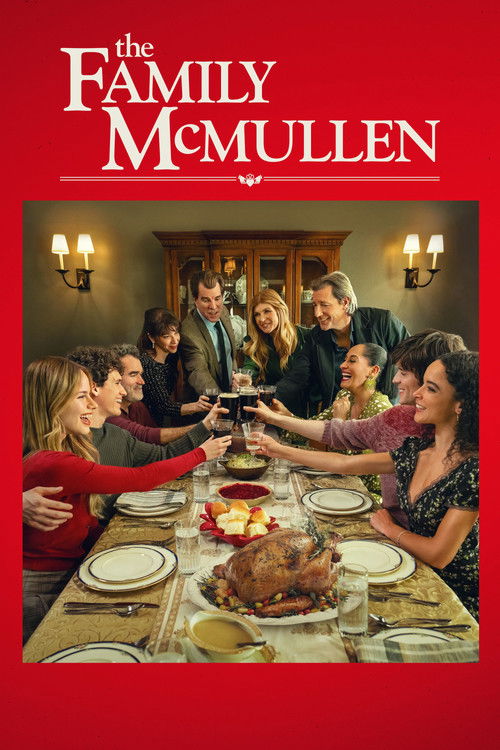

The Architecture of Homecoming

In 1995, Edward Burns captured the grainy, anxious pulse of Gen X masculinity in *The Brothers McMullen*, a film famously shot on a shoestring budget that felt like eavesdropping on a Long Island kitchen confession. Thirty years later, the grain is gone, replaced by the crisp, digital polish of *The Family McMullen* (2025). Yet, despite the visual upgrade and the inevitable softening of age, the McMullen nervous system remains intact. Burns has not just made a sequel; he has constructed a cinematic echo chamber where the anxieties of the past reverberate through a new generation, proving that while you can renovate the house, you can’t renovate the haunting.

To view this film solely as a nostalgia vehicle is to miss the subtle tragedy beneath its "hangout movie" veneer. The narrative architecture mirrors the original—adult children retreating to the family nest to lick their wounds—but the stakes have shifted from the theoretical fears of commitment to the concrete scars of loss. The most deafening presence in the film is an absence: Jack, the eldest brother and moral anchor of the original, is dead. His widow, Molly (a radiant, grounded Connie Britton), navigates a grief that gives the film its ballast. When we see the surviving brothers, Barry (Burns) and Patrick (Michael McGlone), circling the same kitchen island, their banter is no longer just "Irish-Catholic guilt" played for laughs; it is the defensive crouch of men who realize they are now the patriarchs of a dysfunction they once mocked.

Visually, Burns trades the claustrophobic 16mm close-ups of the 90s for wider, airier compositions. This aesthetic choice is telling. In their twenties, the brothers were suffocated by their proximity; in their fifties, they are isolated by their choices. The "walk and talk" scenes—a Burns signature—are present, but they feel less like frantic escapes and more like measured constitutionals. The camera lingers on the spaces between the actors, emphasizing the emotional distances that decades of unspoken resentments have carved out. The digital clarity acts almost like a harsh fluorescent light, exposing the lines on faces that were once smooth with arrogance.

The film’s heart beats strongest in the interplay between the "legacy" cast and the newcomers. Barry’s children, Tommy (Pico Alexander) and Patty (Halston Sage), are essentially remixes of their father and uncles, trapped in the same loop of romantic self-sabotage. There is a particularly biting irony in seeing Barry, once the commitment-phobic cynic, try to parent a son who treats relationships with the same careless disposability Barry once championed. The scene where Patrick—whose wide-eyed idealism has curdled into a confused mid-life separation—quotes the adage about "going home again" lands with a thud of melancholy. It acknowledges that the "home" they have returned to is a museum of their former selves.

Ultimately, *The Family McMullen* is a film about the terrifying stickiness of DNA. It argues that we do not merely inherit our parents' eyes or hair, but their emotional blind spots. Burns has crafted a film that feels like a warm embrace from an old friend who knows exactly where you failed, yet pours you a drink anyway. It is not a revolutionary piece of cinema, nor does it try to be. Instead, it is a sturdy, well-worn structure—a testament to the enduring, maddening comfort of the people who knew us when we were young, and the terrifying realization that we have become them.