✦ AI-generated review

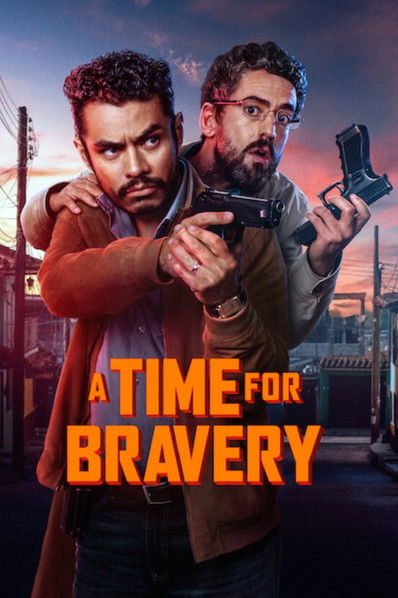

Therapy at 100 Miles Per Hour

The "Buddy Cop" genre, for all its durability, often feels like a relic of a louder, less introspective era. It relies on the friction between two incompatible caricatures—the loose cannon and the by-the-book straitlaced officer—solving crimes through ballistics rather than dialogue. However, in *A Time For Bravery* (*La hora de los valientes*), director Ariel Winograd attempts a fascinating inversion of this trope. By remaking Damián Szifron’s beloved 2005 Argentine classic, Winograd isn't just importing a script to Mexico; he is updating the machinery of male bonding for a year where emotional intelligence is as crucial as a loaded weapon.

Winograd, a filmmaker who has carved a niche in high-concept commercial comedy (*El robo del siglo*, *Sin hijos*), approaches this material with a sleek, polished visual language that fits comfortably within the Netflix gloss, yet occasionally yearns for something grittier. The film’s central conceit—a neurotic psychoanalyst (Luis Gerardo Méndez) sentenced to community service as a "therapeutic companion" to a depressed federal agent (Memo Villegas)—transforms the patrol car into a mobile confessional.

Visually, the film thrives in these claustrophobic automotive moments. Winograd frames the windshield not just as a window to the crime-riddled streets of Mexico City, but as a screen onto which the characters project their insecurities. The car becomes a bubble of vulnerability moving through a hostile world. The director uses tight two-shots to emphasize the forced intimacy of the arrangement. When the action inevitably explodes outside the vehicle—involving a conspiracy that feels delightfully high-stakes yet absurd—the camera moves with a fluidity that contrasts sharply with the emotional stasis of the protagonist inside. The violence is kinetic, but the *real* impact occurs in the passenger seat, where silence is more terrifying than gunfire.

At the film's heart lies a deconstruction of stoic masculinity. Memo Villegas plays the agent not as a roguish hero, but as a man hollowed out by infidelity and professional burnout. He is a vessel of sorrow in a kevlar vest. Opposite him, Luis Gerardo Méndez brings a frantic, verbal energy that acts as a shield against his own cowardice. The script’s brilliance lies in how it forces these two to trade roles: the analyst must learn to act physically, and the cop must learn to speak emotionally. There is a particularly resonant sequence where a high-speed pursuit is interrupted by a breakthrough in their session; it is funny, yes, but it also underscores the film’s thesis that true bravery is not suppressing fear, but articulating it.

However, the film does not entirely escape the shadow of its predecessor. Szifron’s original possessed a shaggy, unpredictable indie spirit that felt dangerous. Winograd’s adaptation, by contrast, feels safer—a well-oiled machine designed to hit emotional beats with metronomic precision. The narrative occasionally collapses under the weight of its own slickness, smoothing over the rougher, more human edges that make a story linger. The third-act conspiracy involving national security feels like necessary genre furniture rather than an organic escalation, reminding us that we are, after all, watching a product designed for global streaming consumption.

Ultimately, *A Time For Bravery* succeeds because it prioritizes the soul over the spectacle. It suggests that in a world defined by chaos, the most radical act two men can commit is not saving the city, but saving each other from despair. It is a film that argues, quite convincingly, that sometimes the most important backup a cop can call for is a good listener.