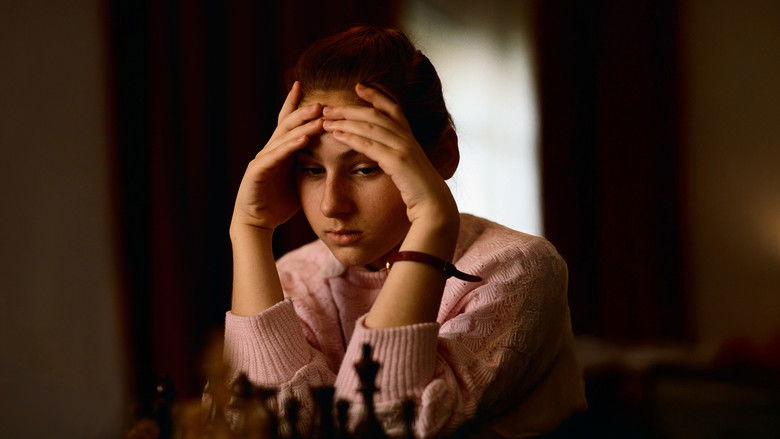

The Architecture of GeniusTo view the life of Judit Polgár merely as a sports triumph is to misunderstand the terrifying ambition of her origin story. Before she was a grandmaster, she was a hypothesis. In *Queen of Chess*, director Rory Kennedy presents us with a narrative that is nominally about sixty-four squares, but is fundamentally about the eerie, constructed nature of greatness. The film posits a question that haunts every frame: If you dismantle the childhood of a young girl and replace it with an obsessively curated algorithm for victory, what remains of the human spirit?

Kennedy, a filmmaker who has navigated the collapse of war zones (*Last Days in Vietnam*), here turns her lens to a different kind of conflict zone: the claustrophobic apartment in communist Budapest where László Polgár waged a war against the concept of "talent." His theory—that any child could be molded into a genius—serves as the film’s brutal, fascinating incitement.

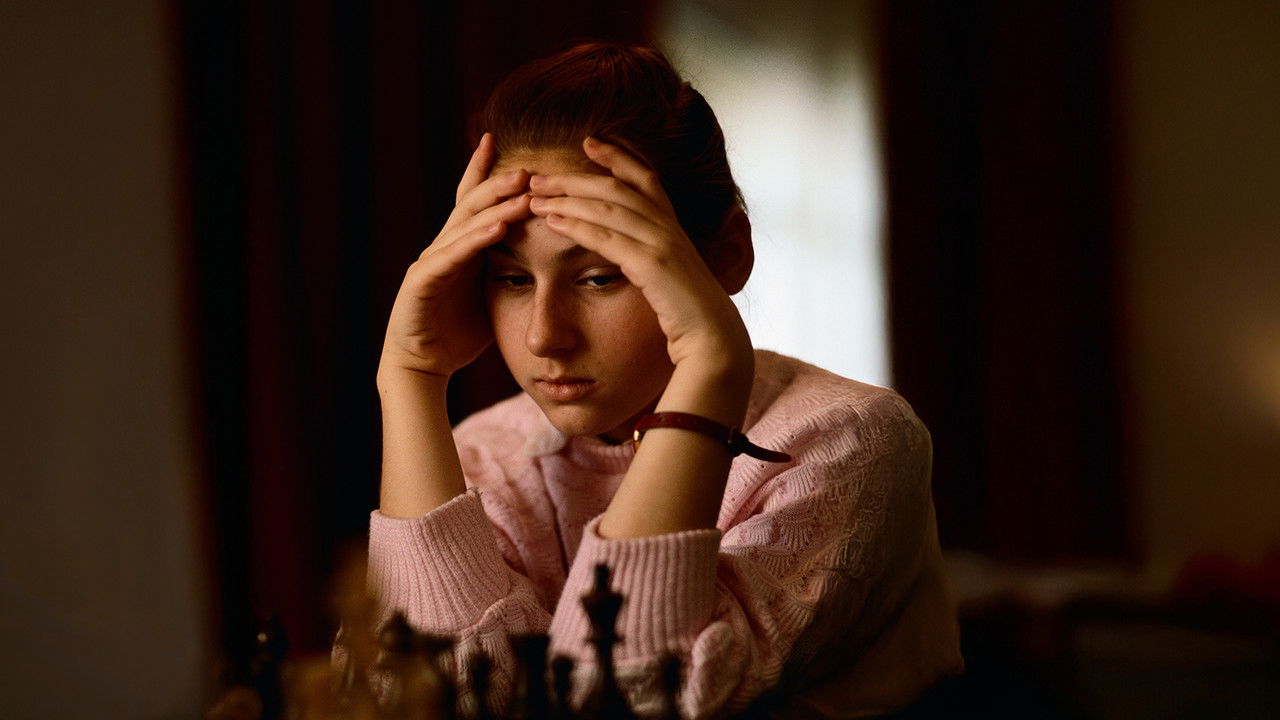

Visually, Kennedy rejects the sterile silence usually associated with the sport. She understands that for Judit, chess was not a quiet parlor game but a gladiator pit. The film’s aesthetic is kinetic, almost aggressive, utilizing a soundtrack pulsating with female-fronted punk and rock—tracks by Blondie and Elastica—to underscore the disruption Judit represented to the male establishment. The editing cuts through archival footage of 1970s Hungary with a sharpness that mirrors Judit’s own aggressive attacking style on the board.

However, the film’s visual language occasionally succumbs to the glossy, accessible sheen typical of modern streaming documentaries. While the graphical visualizations of chess strategies—the Sicilian Defense, the Berlin Wall—are rendered with clarity for the layperson, they sometimes feel like digital overlays on a story that demands more grit. We see the moves, but we don't always feel the suffocating pressure of the air in the room.

The emotional anchor of the film is not the relationship between father and daughter, which is treated with a surprisingly gentle touch, but the gladiatorial rivalry between Judit and World Champion Garry Kasparov. Here, the documentary finds its sharpest teeth. Kasparov appears not just as an opponent, but as the personification of the old world—a titan who once dismissed female players as "circus puppets."

Kennedy brilliantly deconstructs their encounters, particularly the infamous 1994 touch-move controversy, where the camera lingers on the microscopic deceit of a champion rattled by a teenage girl. The narrative builds toward their 2002 match, framing it less as a game and more as an exorcism of the sport’s patriarchal ghosts. Yet, in its rush to celebrate Judit’s resilience, the film arguably pulls its punches regarding the ethical darkness of her father's experiment. We see the glory of the "made" genius, but the psychological cost is smoothed over in service of an inspiring, triumphant arc.

Ultimately, *Queen of Chess* succeeds because Judit herself refuses to be a victim of her own biography. She emerges not as a robotic product of her father’s laboratory, but as a woman of profound, quiet warmth who hijacked the experiment and made it her own. While the film may lack the cinematic danger of the events it depicts—smoothing out the jagged edges of obsession—it stands as a compelling testament to a mind that refused to be checkmated by biology or tradition. It is a study of a woman who learned to play the game better than the men who invented the rules, only to realize the board was too small for her all along.