✦ AI-generated review

The Architecture of Loss

Cinema rarely offers second chances, yet it frequently demands them of its myths. When Marc Webb’s *The Amazing Spider-Man* arrived in 2012, it walked into a theater darkened by the shadow of Sam Raimi’s vibrant, pop-art trilogy. The cultural skepticism was palpable; the dust had barely settled on the previous iteration before audiences were asked to witness the murder of Uncle Ben all over again. However, to dismiss Webb’s interpretation as a mere commercial redundancy is to overlook the specific, jagged emotional frequency it broadcasts. This is not a film about a superhero rising; it is a film about a boy drowning, flailing for a raft in a sea of abandonment.

Webb, fresh off the indie success of *(500) Days of Summer*, applies a lens that feels less like a comic book panel and more like a music video for a post-punk ballad. Where his predecessor favored the bright, primary colors of the Silver Age, Webb plunges New York into an eternal, wet twilight. The cinematography is moody and tactile; we feel the damp cold of the skyline and the scuffed texture of the suit, which looks like it was stitched together from stolen athletic gear. Webb’s most daring visual flourish—the first-person perspective sequences during the web-swinging—does more than provide a thrill. It traps us inside the mask, forcing the audience to share Peter Parker’s vertigo. We aren't watching a god fly; we are watching a teenager falling with style.

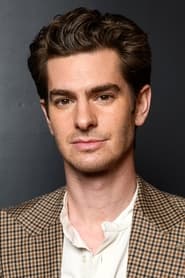

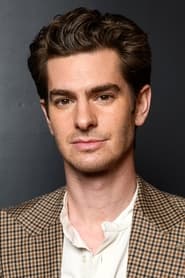

At the center of this gravity is Andrew Garfield, whose Peter Parker is a departure from the earnest, wide-eyed archetype. Garfield plays Parker as a wound that hasn't healed. He is twitchy, intellectually arrogant, and brimming with a nervous, kinetic energy that borders on aggression. This Peter is not just a nerd; he is an outcast by circumstance, haunted by the empty spaces his parents left behind. His heroism is born not initially from altruism, but from a desperate need to impose order on a chaotic life.

This emotional reality is anchored by the presence of Gwen Stacy, played by Emma Stone. To call their dynamic "romantic" feels reductive; it is the film’s vital organ. Webb directs their scenes with the intimacy of a mumblecore drama. The hallway conversations, filled with overlapping dialogue and awkward pauses, feel painfully authentic. Gwen is not a prize to be won but an intellectual equal who sees through the performance of Peter’s bravado. When the narrative threatens to collapse under the weight of genetic conspiracies and lizard-men, it is the silence between Garfield and Stone that holds the structure together.

The antagonist, Dr. Curt Connors (Rhys Ifans), serves as a tragic mirror to Peter’s isolation. Connors is a man trying to fix himself, to regrow what was lost, a literalization of Peter’s internal desire to restore his broken family unit. The tragedy of the film is that both men use science to fill a void, but where Peter finds connection, Connors loses his humanity.

*The Amazing Spider-Man* is an imperfect beast, occasionally stumbling over its own mystery-box plotting. Yet, it succeeds in a way few blockbusters dare to attempt: it prioritizes the bruise over the punch. It posits that the mask is not a symbol of power, but a hiding place for a grieving child. In the modern landscape of polished, interconnected cinematic universes, Webb’s film stands as a raw, melancholic artifact—a reminder that before a hero can save the world, he must first survive himself.