✦ AI-generated review

The Nightmare in the Machine

Great cinema often arrives not as a calculated commercial proposition, but as a fever dream. In the case of James Cameron’s *The Terminator*, this is quite literal—the director, ill and broke in Rome, envisioned a chrome torso dragging itself from an explosion, holding kitchen knives. From this nocturnal terror emerged a film that is frequently misremembered as merely a muscular action vehicle. In truth, *The Terminator* is a relentless sci-fi slasher, a piece of "tech-noir" that uses the language of violence to explore the fragility of the human body against the cold indifference of the machine.

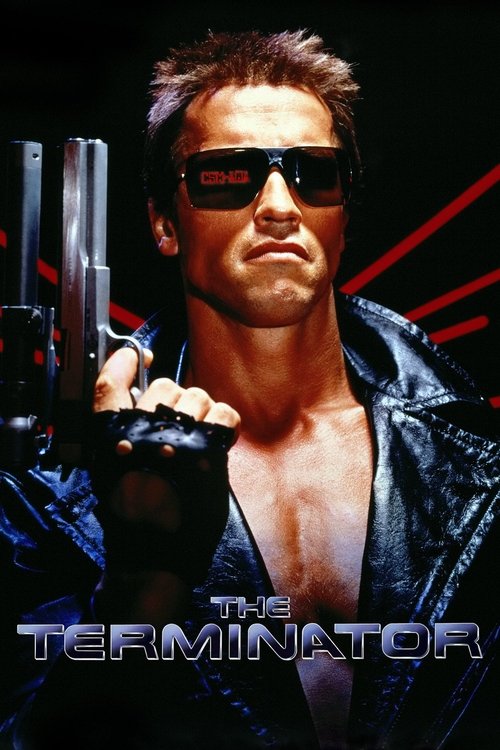

To view this film solely through the lens of its explosive legacy is to miss the desperate, gritty texture of the original 1984 release. Cameron, working with a shoestring budget, does not offer the glossy, liquid-metal sheen of his later sequels. Instead, he presents a Los Angeles that feels suffocatingly industrial—a world of steam, blue steel, and long shadows. The cinematographer, Adam Greenberg, bathes the film in a sickly, fluorescent night-light, creating a visual landscape where the future feels like a trash-strewn alleyway. This aesthetic choice is not just budgetary; it is thematic. The "Tech Noir" nightclub scene, where the narrative’s three central bodies finally collide, encapsulates this perfectly. As the synthesizer pulse of the soundtrack slows to a heartbeat, the laser sight of the Terminator’s pistol cuts through the fog—a red eye of technology seeking to erase a human life. It is a sequence of pure, claustrophobic dread.

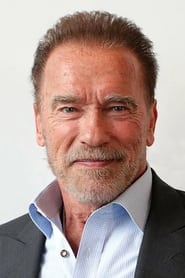

At the center of this metallic storm is a casting decision that remains one of the most serendipitous accidents in film history. Arnold Schwarzenegger, an actor of limited range but immense physical presence, turns his limitations into a terrifying asset. His Terminator is not a villain in the traditional sense; he is a force of nature, an inevitability. There is no malice in his performance, only function. By stripping the antagonist of ego or sadism, Cameron creates a horror that is far more profound than a typical movie monster: the horror of an object that simply *will not stop*.

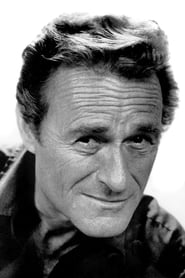

Yet, the film’s enduring power lies not in the robot, but in the desperate humanity of its protectors. Michael Biehn’s Kyle Reese is a heartbreaking creation—a soldier who has known nothing but ash and ruin, who travels across time not for glory, but for the love of a photograph. He is lean, scarred, and perpetually exhausted, a stark contrast to the Austrian oak he must fight. The film’s emotional core is found in the quieter moments between Reese and Linda Hamilton’s Sarah Connor. Their intimacy in a cheap motel room is not a gratuitous interlude; it is an act of defiance. In a universe governed by deterministic machines and nuclear fire, their connection asserts that biology, messiness, and love are the only weapons we have left.

Sarah Connor herself begins not as a warrior, but as a bored waitress whose biggest concern is a stood-up date. Her transformation is not the sudden acquisition of superpowers, but a painful shedding of innocence. By the film’s end, as she drives toward a storm in the Mexican desert, she carries the weight of a future that she did not ask for. She has become a ghost in her own time, separated from the mundane world by the terrible knowledge she possesses.

*The Terminator* remains a masterpiece because it understands that technology is not the enemy; the enemy is our own obsolescence. It is a film about the terrifying realization that the tools we build may one day outlast us, and that in the face of such cold logic, the most radical thing we can do is survive. It is a B-movie with the soul of a Greek tragedy, warning us that while the future is not set, the storm is always coming.