The Age of BarbarismIt is a curious paradox of modern South Korean media that the nation’s most traumatic decades—the military dictatorships of the 1970s and 80s—have become its most stylish export. Director Woo Min-ho has spent a career excavating this era, turning the grime of political corruption into the high-gloss noir of *Inside Men* and *The Man Standing Next*. With *Made in Korea*, his first foray into serialized storytelling, Woo returns to the "age of barbarism," but the canvas has expanded. This is not merely a crime drama; it is a sprawling, suffocating portrait of a nation building its identity on a foundation of illicit ambition and state-sanctioned violence.

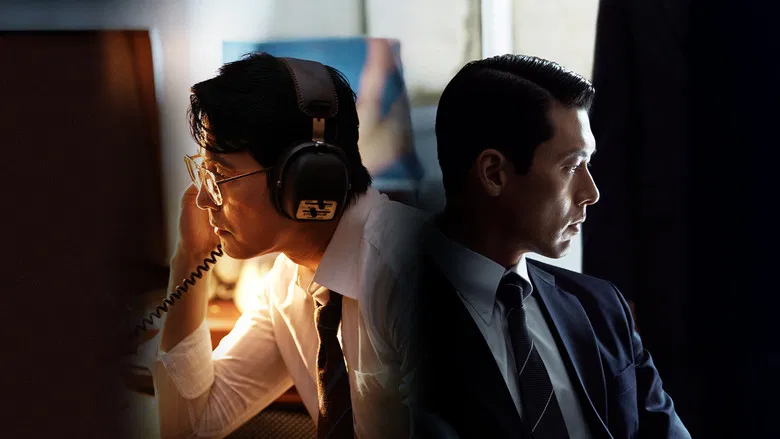

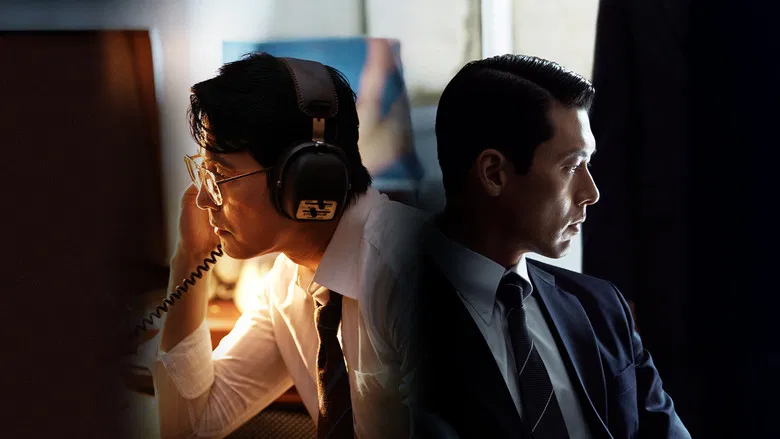

Visually, the series is a triumph of texture. Woo and his cinematographer trade the digital sheen of modern K-drama for a palette of tobacco-stained browns, sickly greens, and the harsh fluorescent glare of interrogation rooms. The 1970s here are not nostalgic; they are humid and oppressive. The camera lingers on the physical manifestations of power—the heavy wooden desks of the KCIA, the slicked-back hair of men who decide who lives or dies, and the endless plumes of cigarette smoke that seem to obscure the truth as much as the dialogue does. It creates a world where the line between a government official and a gangster is not just blurred; it is non-existent.

At the center of this moral rot is Baek Ki-tae, played with reptilian charisma by Hyun Bin. Casting the nation’s romantic lead as a ruthlessly ambitious KCIA operative is a masterstroke. Hyun sheds his usual warmth for a cold, calculating stillness. He plays Ki-tae not as a villain twirling a mustache, but as a survivalist who understands that in a lawless state, one must be the law. His performance is a study in controlled chaos; he is a man who can order a hit and negotiate a trade deal with the same flat affect. This is the "Korean Dream" curdled—the belief that upward mobility justifies any sin.

Opposing him is Jung Woo-sung as prosecutor Jang Geon-young, a character who feels like a spiritual continuation of the director's previous archetypes of frustrated justice. Jung’s performance has been divisive, leaning into a manic, almost feral energy that contrasts sharply with Hyun’s icy reserve. While some may find his shouting jagged, it serves a thematic purpose: in a system designed to silence dissent, the only way to be heard is to scream. The dynamic between the two men is less a cat-and-mouse game and more a collision of two immovable historical forces—the unchecked state power and the desperate, often futile, grasp for the rule of law.

The series does falter occasionally under the weight of its own runtime. The transition from film to a six-episode arc exposes some pacing issues, where the tension slackens in favor of exposition that a tighter script might have elided. However, the show regains its footing in its set pieces, particularly the hijacking sequence in the first episode, which serves as a microcosm for the show’s entire philosophy: innocent lives are merely poker chips in a high-stakes game played by powerful men in suits.

Ultimately, *Made in Korea* is a cynical love letter to a country that forged its modernity in blood. It suggests that the shiny, exportable culture of today was bought and paid for by the "made in Korea" brand of the 1970s—a brand stamped on bags of illicit cash and classified documents. It is a demanding watch, one that asks us to look past the stylish suits and see the monsters wearing them. In doing so, it cements itself not just as a piece of entertainment, but as a necessary, if uncomfortable, reflection in the national mirror.