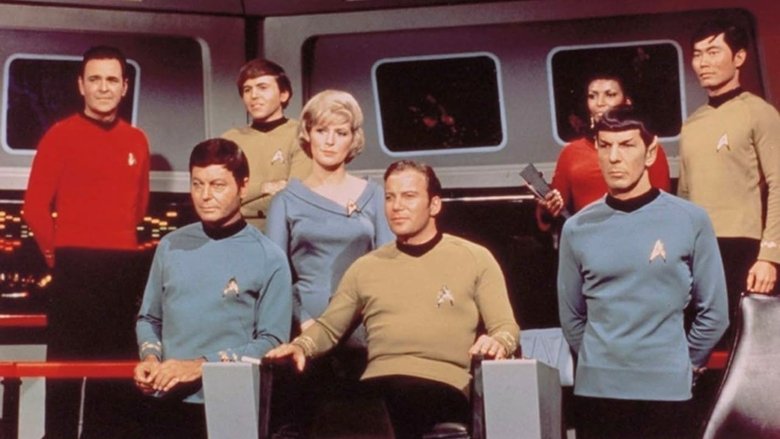

The Architecture of HopeIn 1966, the real world was holding its breath. The Cold War had frozen geopolitics into a terrifying stalemate, racial tensions in America were reaching a boiling point, and the threat of nuclear annihilation was a daily weather report. Into this atmosphere of suffocating dread arrived *Star Trek*, a television series that didn't just offer escapism; it offered a counter-argument to the 20th century. While Gene Roddenberry famously pitched his creation as "Wagon Train to the stars" to appease studio executives hungry for a space-western, the resulting work was something far more subversive: a moral sandbox where humanity had not only survived its self-destructive infancy but had matured into a species capable of infinite curiosity.

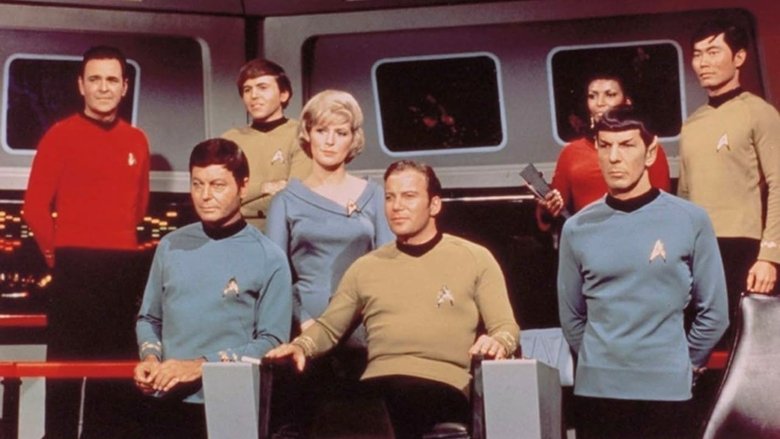

To watch the original series today requires an adjustment of one’s visual palate. We must look past the styrofoam boulders and the velour uniforms that shrink in the wash. Yet, there is a distinct, theatrical beauty to the show’s limitations. Because the budget could not afford the sprawling CGI vistas of modern cinema, *Star Trek* functioned like a stage play. The bridge of the U.S.S. Enterprise is not just a command center; it is a forum. The blocking of the actors, the primary-colored lighting (designed to sell the new technology of color television), and the tight close-ups force the audience to focus on the dialogue and the philosophical conflict at hand. The "cheapness" of the sets paradoxically elevates the material, stripping away the distraction of spectacle and leaving only the naked strength of the ideas.

At the heart of this interstellar stage play is a trinity of archetypes that remains unrivaled in genre fiction: the Logic (Spock), the Emotion (Dr. McCoy), and the Will (Captain Kirk). The show’s brilliance lies in how it refuses to let any single viewpoint win. In episodes like the tragic masterpiece "The City on the Edge of Forever," we see this engine at full throttle. Spock argues the cold utilitarian necessity of letting a good woman die to save the timeline; McCoy screams for the immediate, human imperative to save a life. Kirk, the synthesis of the two, must bear the crushing weight of the final decision. This is not a show about shooting aliens; it is a show about the agony of leadership and the cost of doing the right thing.

The cultural footprint of *Star Trek* is often measured in its predictions of technology—automatic doors, communicators, tablets—but its true prescience was sociological. By placing a Russian, a Japanese man, an African woman, and an alien on the same bridge during the height of the Cold War and the Civil Rights movement, Roddenberry was engaging in visual activism. He posited that our differences would not be erased by the future, but rather integrated into our strength.

Ultimately, *Star Trek* endures not because of its warp drives or phasers, but because of its radical, defiant optimism. In an era where modern prestige TV often equates darkness with depth, there is something profoundly moving about a series that dares to suggest that we are going to make it. It demands that we look at the unknown not with fear, but with an open hand.