✦ AI-generated review

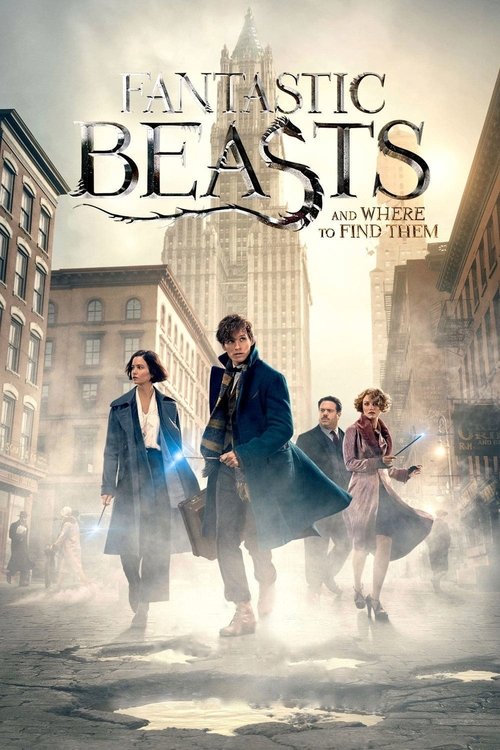

The Suitcase and the Shadow

When David Yates took the helm of the *Harry Potter* series in its later years, he drained the saturation, replacing the amber warmth of Hogwarts with a steel-grey pallor that signaled the end of childhood. In *Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them* (2016), Yates doubles down on this aesthetic, presenting a 1926 New York that is architecturally imposing and spiritually suffocating. This is not a film about the whimsy of magic; it is a film about the violence of repression, and the quiet, radical empathy required to survive it.

The narrative ostensibly follows Newt Scamander (Eddie Redmayne), a British magizoologist who arrives in America with a leather case full of illegal creatures. However, the film’s true subject is the friction between the organic and the industrial. Yates and cinematographer Philippe Rousselot shoot New York as a canyon of shadows and hard angles, a place where the American wizarding government (MACUSA) operates with a bureaucratic coldness that rivals the non-magical world’s Prohibition-era austerity. In this setting, magic is not a gift to be celebrated but a dangerous variable to be policed.

Into this rigid geometry steps Newt Scamander, a protagonist who defies the archetype of the blockbuster hero. He is not a "Chosen One" destined to defeat a Dark Lord through martial prowess; he is an awkward, averting-eyes academic who prefers the company of Bowtruckles to people. Redmayne’s performance is a masterclass in physical diffidence—he hunches, mumbles, and angles his body away from conflict. Yet, this is not weakness. The film argues that Newt’s "soft" masculinity—his impulse to nurture rather than dominate—is the only antidote to the film’s central threat.

That threat is the Obscurus, a dark, parasitic force created when a magical child is forced to suppress their nature. It is here that J.K. Rowling’s screenplay taps into a profound, if occasionally blunt, allegory for the closet. The tragic antagonist, Credence Barebone (Ezra Miller), is being beaten into submission by a religious zealot, his magic curdle into a black, destructive wind because it has no outlet. The visual contrast is stark: the Obscurus is a formless, chaotic void that shatters the city, while Newt’s suitcase—a TARDIS-like sanctuary—is a lush, golden Eden where strange beasts are allowed to simply *be*.

The film creates a dichotomy between "preservation" and "extermination." The American wizards, governed by fear of exposure, mirror the fanaticism of the "Second Salemers" who want to burn them. Both sides seek to control or destroy what they don't understand. Newt, conversely, represents the radical act of understanding. The sequence where he introduces the "No-Maj" Jacob Kowalski (a delightfully grounded Dan Fogler) to his menagerie is the film’s emotional anchor. It is a plea for conservation, not just of animals, but of the eccentricities that make us human.

While the film occasionally labors under the weight of world-building, pausing to set up future conflicts rather than resolving current ones, its heart remains surprisingly intimate. It suggests that the greatest danger to society is not the "beast" roaming the streets, but the monster we create when we force difference into the dark. In a cinematic landscape often obsessed with power, *Fantastic Beasts* dares to suggest that the most powerful magic is simply paying attention to the things others ignore.