✦ AI-generated review

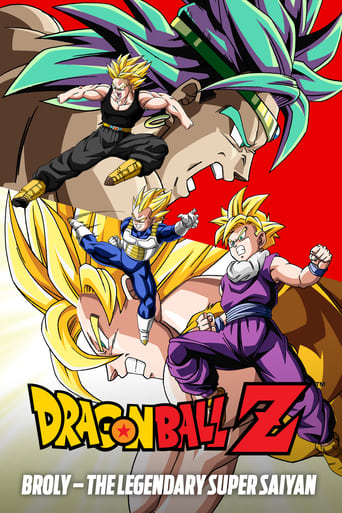

The Architecture of Fear

In 2005, the superhero genre was largely defined by two distinct poles: the brightly colored, toy-ready camp of the late 1990s and the burgeoning, CGI-heavy spectacle of early Marvel adaptations. Cinema treated the comic book hero as a figure of fantasy, detached from the laws of physics and the grit of the pavement. Then came Christopher Nolan’s *Batman Begins*, a film that dared to suggest that the most fantastical element of a superhero story wasn’t the cape or the gadgets, but the psychological scar tissue of the man wearing them. Nolan did not simply reboot a series; he dismantled a pop-culture icon and rebuilt him, piece by agonizing piece, in a world that looked uncomfortably like our own.

To understand the weight of *Batman Begins*, one must look at how it rejects the gothic expressionism of Tim Burton and the neon excess of Joel Schumacher. Nolan, alongside cinematographer Wally Pfister, traded stylized gargoyles for the wet, sodium-lit streets of a recognizable metropolis. This Gotham is not a dreamscape; it is a failing state, rotting from economic depression and institutional corruption. By grounding the setting in a tactile reality—shooting on location in Chicago and London—Nolan forces the audience to accept the Batman not as a creature of the night, but as a desperate, tactical response to a city that has lost its way.

This obsession with "grounded" realism extends to the film’s visual language. Nolan is fascinated by process. We are not asked to suspend our disbelief that a billionaire could fly across rooftops; we are shown the military prototypes, the spelunking gear, and the spray paint. We watch Bruce Wayne forge the armor and weld the grapple gun. This procedural approach, often clinical in its precision, serves a crucial narrative function: it demystifies the superhero to humanize the man. When Christian Bale’s Batman finally descends upon the corrupt detective Flass, he is terrifying not because he is a monster, but because we understand the immense human effort required to become that shadow.

At its heart, however, *Batman Begins* is a drama about fear—weaponizing it, conquering it, and succumbing to it. Christian Bale delivers a performance of bifurcated identity that anchors the film’s emotional stakes. There is the hollow, angry young man seeking vengeance; the vapid, champagne-swilling playboy mask he wears for the public; and the terrifying force of nature he becomes in the suit. But the film’s most poignant relationship is not between Batman and his enemies, but between Bruce and his butler, Alfred (played with heartbreaking warmth by Michael Caine). The recurring motif—“Why do we fall? So we can learn to pick ourselves up”—transforms the narrative from a revenge fantasy into a meditation on resilience.

The antagonists, too, reflect this internal struggle. Liam Neeson’s Ra’s al Ghul is not a cackling caricature but a fanatical idealist, a dark mirror reflecting Bruce’s own desire for absolute justice. Their conflict is ideological as much as it is physical, debating whether a civilization is worth saving when it has eaten itself from the inside out.

*Batman Begins* proved that the summer blockbuster could be intelligent, patient, and profoundly human. It treated the source material not as "content" to be exploited, but as a modern myth capable of bearing the weight of serious drama. By stripping away the fantasy, Nolan revealed the tragedy beneath the cowl, giving us a hero defined not by his ability to fight, but by his refusal to stay down.