The Weight of DesireThe genre of *xianxia*—Chinese high fantasy rooted in Taoist mythology—often suffers from a specific kind of weightlessness. Its characters float on clouds, its stakes are abstractly cosmic, and its conflicts are frequently resolved by beams of colored light. It is a bold, perhaps even perilous choice for director Jizhou Xu to step into this ethereal arena. Known for the gritty, textured crime drama of *The Knockout*, Xu brings a surprising heaviness to *The Unclouded Soul*. He treats the fantastical not as a playground for CGI spectacles, but as a rigid ecosystem of consequences, where the pursuit of immortality is not a noble quest, but a terrifying addiction.

Visually, the film (presented here in its episodic structure) operates on a polarity of suffocation and release. The Valley of Ten Thousand Demons is not merely a setting; it is a psychological architecture. Xu creates a visual language where the environment mirrors the internal state of the Demon King, Hong Ye. The lighting is often low, the palette bruised with indigos and charcoals, suggesting a world tired of its own existence. This makes the intrusion of Xiao Yao, often costumed in vibrant, defiant yellows, feel like a genuine disruption of the status quo. The camera lingers on the textures of the set design—the moss on ancient stone, the ripple of the Jade Liquor Spring—grounding the magic in a tactile reality that many genre contemporaries lack. It asks us to believe in this world not because it looks magical, but because it feels lived-in and decaying.

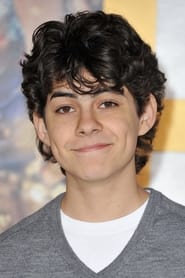

At the narrative's heart lies a meditation on time and purity. Hou Minghao’s performance as Hong Ye avoids the trap of the brooding, romantic anti-hero. Instead, he plays the Demon King with a profound sense of exhaustion. This is a being who has seen the cyclic nature of history and found it wanting. His stillness is not a pose; it is the lethargy of someone burdened by centuries of observing human greed. Against him, Tan Songyun’s Xiao Yao could have easily devolved into the "manic pixie" archetype common in fantasy romances. However, the script allows her a sharp, survivalist intelligence. She is "unclouded" not because she is naive, but because she rejects the transactionality that governs the worlds of both humans and demons. The chemistry between them works because it is dialectical: he represents the accumulation of the past, while she embodies the immediacy of the present.

The central MacGuffin, the Jade Liquor Spring, serves as a potent metaphor for the narrative's central thesis: desire as corruption. In Xu’s hands, the "strange cases" the duo investigates are not just procedural filler; they are vignettes illustrating the varied pathologies of greed. Whether it is humans seeking eternal youth or demons seeking cultivation power, the film posits that the inability to accept mortality is the root of all violence.

Ultimately, *The Unclouded Soul* succeeds because it uses the trappings of fantasy to tell a deeply human story about the difficulty of remaining decent in an indecent world. It suggests that the true superpower is not flying on swords or casting spells, but maintaining an unclouded soul when the entire world is demanding you sell it. It is a visually arresting, surprisingly melancholy work that proves the *xianxia* genre still has new depths to plumb when placed in the hands of a filmmaker interested in the soul beneath the silk robes.