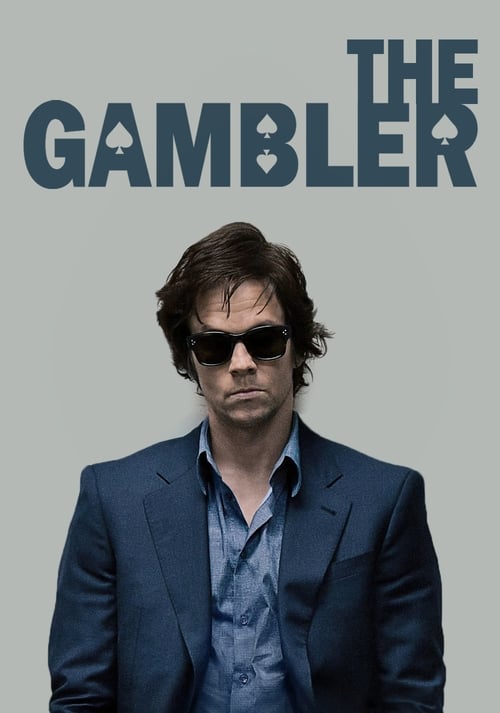

The Glossy VoidCinema has long been fascinated by the self-destructive man, the figure who stands at the edge of the abyss not because he slipped, but because he is curious about the fall. Rupert Wyatt’s 2014 remake of *The Gambler* is a polarizing entry in this canon. Where the 1974 original, penned by James Toback and starring James Caan, was a gritty, sweaty portrait of 70s addiction, Wyatt’s interpretation is a sleek, icy creature. It is less about the dirt of the soul and more about the architecture of nihilism. It poses a question that is distinctly modern: when a man has everything—wealth, tenure, talent—why does the void look so much more appealing than the summit?

To understand this film, one must first look at how Wyatt chooses to photograph it. The director, previously known for the kinetic *Rise of the Planet of the Apes*, here adopts a visual language of suffocating crispness. The Los Angeles of *The Gambler* is not the sun-drenched land of dreams, but a nocturnal grid of blue neon, black leather, and sterile lecture halls. The cinematography creates a world that feels hermetically sealed, trapping the protagonist, Jim Bennett (Mark Wahlberg), in a cage of his own privilege. The film does not look like a desperate scramble for cash; it looks like a high-end fashion spread for the terminally depressed. This "glossiness" is often cited as a flaw by critics who crave the graininess of the 70s, but it serves a specific narrative function: it emphasizes that Bennett’s problem isn't money. He has access to money. His problem is that he is allergic to the safety it provides.

At the center of this frozen world is Mark Wahlberg, delivering a performance of aggressive, weaponized apathy. As a literature professor who tells his students that they are either geniuses or nothing, Bennett is deeply unlikable—a feature, not a bug, of William Monahan’s razor-sharp script. Wahlberg sheds his usual earnest heroics for a gaunt, prickly hostility. He moves through the film like a ghost haunting his own life, seeking pain to verify his existence. However, the film finds its gravity in John Goodman’s Frank, a loan shark who operates with a paternal, terrifying warmth. Goodman’s monologue on the concept of "F-You" money is the film’s philosophical anchor. He represents the reality that Bennett is fleeing: the stability that allows a man to say "no," which Bennett perversely rejects because he only wants to say "nothing."

Ultimately, *The Gambler* is a fable about the violence of mediocrity. Bennett gambles not to win, but to strip himself of the inheritance and social safety nets that he feels define him falsely. He wants to reach absolute zero. The film’s climax, which deviates significantly from the ambiguous darkness of the 1974 original, suggests a desire for a clean slate rather than total annihilation. It is a frantic sprint toward a silence where the noise of expectation finally ceases. While it may lack the emotional rawness of its predecessor, Wyatt’s film succeeds as a stylized, hypnotic study of a man trying to buy his freedom with the only currency he has left: his life.