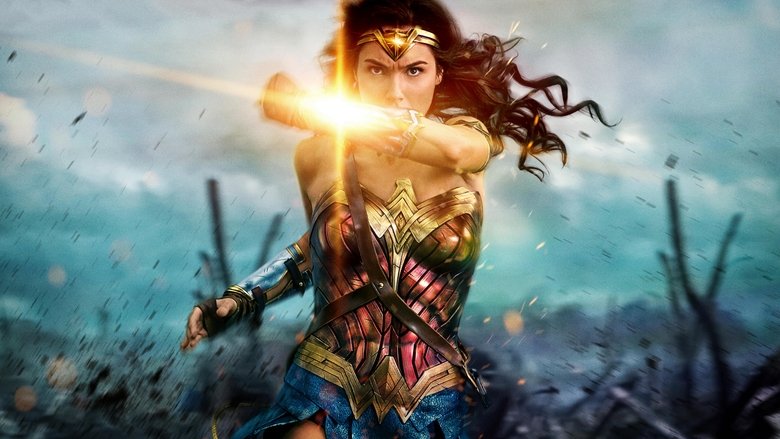

The Myth of InnocenceIn the landscape of modern superhero cinema, there has been a prevailing obsession with deconstruction—a desire to drag gods down to earth and dirty their capes in the grit of "realism." By 2017, the DC Extended Universe had become synonymous with this cynical grayness, offering heroes who seemed burdened, rather than emboldened, by their power. Enter Patty Jenkins’ *Wonder Woman*, a film that felt less like a continuation of a franchise and more like a restoration of a lost ideal. It is a work that dares to suggest that earnestness is not a weakness, and that a hero’s greatest weapon might not be a sword, but a refusal to accept the world’s cynicism.

Jenkins constructs the film on a visual dichotomy that serves as its thematic spine. We begin in Themyscira, an island rendered in the saturated golds, azures, and emeralds of a Renaissance painting. It is a paradise, but one that feels hermetically sealed. When Diana (Gal Gadot) leaves this womb of mythology to enter the "World of Man" during the First World War, the palette violently shifts. The screen is washed in the desaturated grays, browns, and sickly greens of the trenches. This is not merely an aesthetic choice; it is a visual representation of Diana’s internal journey. She is a being of vibrant myth stepping into the crushing, monochromatic reality of industrial slaughter.

The film’s centerpiece, and perhaps one of the most significant sequences in the genre’s history, is the "No Man’s Land" scene. Here, the direction shines by subverting the language of action cinema. Diana does not step out of the trench to defeat a specific villain or to look "cool" in the traditional sense; she steps out to draw fire. It is an act of defiance against the stalemate of war. Jenkins shoots Gadot not with the leering gaze often afforded to female action stars, but with a reverent focus on effort and physicality. When Diana deflects a mortar shell with her shield, it is the breaking of a psychological dam for the soldiers behind her. The camera captures a shift in the atmosphere—the moment where the impossible becomes tangible.

At the heart of the film is the friction between Diana’s absolute moral clarity and the murky complexity of human nature. Gal Gadot’s performance is a miracle of calibration; she plays Diana not as a brooding warrior, but as someone armed with a weaponized naivety. She believes that war is the product of a single corrupting influence—Ares—and that killing him will reset humanity to its default state of goodness. The tragedy, and the maturity, of the script lies in the slow erosion of this belief. Steve Trevor (Chris Pine) serves not just as a love interest, but as the tether to reality, teaching Diana that humanity is capable of terrible things without divine intervention.

However, the film is not without its scars. If the first two acts are a masterclass in character-driven storytelling, the third act collapses under the weight of genre obligations. The nuance of the "humanity is flawed" realization is nearly undone by a CGI-laden final confrontation that feels imported from a lesser movie. The subtle thematic work is temporarily deafened by the noise of a mandatory boss fight, where lighting bolts replace emotional stakes.

Yet, *Wonder Woman* recovers its footing in its final moments. It survives its own climax because the emotional truth of Diana’s choice remains intact: she chooses to protect humanity not because they are deserving, but because she loves them regardless of their flaws. In doing so, Jenkins delivered a film that felt revolutionary by looking backward, channeling the romantic spirit of Richard Donner’s *Superman* to remind us that believing in the good is a radical act.