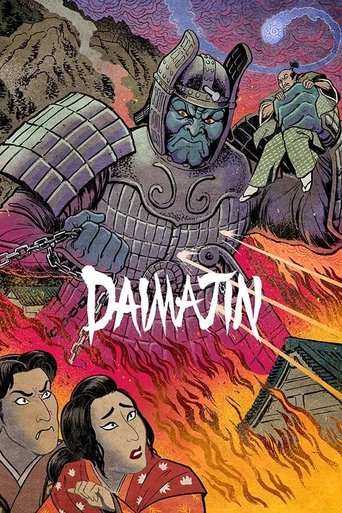

The Sorcery of SurfacesTo adapt George R.R. Martin is usually to invite a certain density—a mud-caked, blood-flecked realism where political machinations grind human bones into dust. Yet, in *In the Lost Lands*, director Paul W.S. Anderson strips Martin’s early prose of its gravitational pull, replacing the heavy soil of Westeros with the weightless, sepia-toned ether of a digital dreamscape. This is not a film about the mechanics of power, as one might expect from the source material, but rather a purely aesthetic exercise in pulp fantasy—a "weird western" that floats, sometimes beautifully and often frustratingly, a few inches above the ground.

Anderson has always been a filmmaker of surfaces, a director who treats architecture and geometry as characters more vital than the humans inhabiting them. Here, the "Lost Lands" are not a geography but a texture. The film is bathed in a relentless, sun-bleached haze, a post-apocalyptic desert that feels less like a location and more like a state of mind. By utilizing vintage anamorphic lenses to capture his green-screen environments, Anderson attempts to graft the DNA of a Sergio Leone western onto a high-fantasy skeleton. The result is jarring, yet undeniably distinct. The visual language is one of isolation; characters are frequently framed as silhouettes against vast, computerized horizons, emphasizing their insignificance in a world that has already ended.

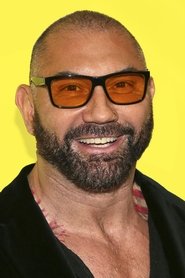

At the center of this artificial wilderness are Gray Alys (Milla Jovovich) and the drifter Boyce (Dave Bautista), two archetypes wandering through the static. Jovovich, Anderson’s perennial muse, plays Alys not as a weary traveler, but as a creature of the environment itself—cool, detached, and dangerously transactional. However, it is Bautista who provides the film’s only tether to emotional reality. In a landscape dominated by "smudgy" CGI and hyper-kinetic editing, Bautista’s stillness is a special effect in its own right. He brings a mournful physicality to Boyce, suggesting a history of violence that the screenplay, penned by Anderson and Constantin Werner, rarely bothers to articulate verbally. Their chemistry is not romantic in the traditional sense, but functional—a mutual recognition of brokenness that gives the film a fleeting, somber heartbeat.

The film struggles most when it attempts to serve two masters: the somber, moralistic fable of Martin’s text and the kinetic, video-game logic of Anderson’s directorial instincts. This friction is most evident in the set pieces. Take, for instance, the sequence involving a hanging bus suspended over an abyss. Visually, it is a marvel of spatial disorientation, with the camera floating backward through the vehicle in a way that defies physics. It is a moment of pure, "trashmonger" imagination that Anderson excels at. Yet, because the world feels so aggressively digital, the peril rarely registers in the gut. We are watching avatars, not people, and the stakes feel as ephemeral as the pixels generating the monsters they fight.

Ultimately, *In the Lost Lands* is a film about the danger of getting exactly what you wish for. The Queen wishes for a power she cannot control, much as the film wishes to be an epic without doing the foundational work of building a reality. It is a work of fascinating contradictions: a visually loud film that is narratively silent, a Western without a frontier. It may not satisfy those looking for the grim humanity of *Game of Thrones*, but as a piece of pop-art surrealism, it offers a strange, suffocating beauty—a postcard from a world that never was.