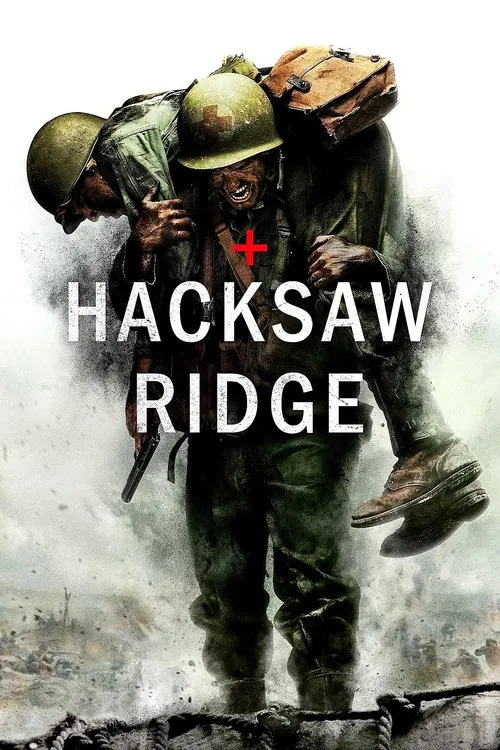

The Flesh and the SpiritIt is a profound irony of modern cinema that Mel Gibson, a director whose public life has been defined by volatility, is perhaps our most articulate chronicler of spiritual serenity amidst physical annihilation. In *Hacksaw Ridge* (2016), Gibson returns from a decade of directorial exile not with a whimper, but with a deafening roar. This is not merely a war film; it is a theological text written in blood and shrapnel. It asks a question that feels almost alien in our cynical age: Can a man walk into the mouth of hell, surrounded by death, and refuse to participate in it, yet still emerge as the bravest soul on the field?

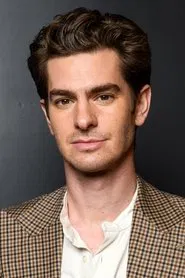

The film’s structure is deceptively bifurcated, operating like a diptych of American mythology. The first hour, set in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia, is bathed in the golden, nostalgic glow of a Norman Rockwell painting. We meet Desmond Doss (Andrew Garfield), a Seventh-day Adventist whose pacifism is forged in the fires of a traumatic childhood and a violent, alcoholic father. These early scenes, while occasionally flirting with melodrama, establish the "why" of Doss’s conviction. Gibson needs us to believe in Doss's innocence so that its collision with the reality of Okinawa is all the more shattering. When the film transitions to the Pacific Theater, that golden light is extinguished, replaced by a desaturated, muddy nightmare that recalls the visceral horror of Hieronymus Bosch.

Gibson has never been a subtle director, and here his "cinema of suffering" finds its perfect subject. The violence on Hacksaw Ridge is not action-movie kineticism; it is a meat grinder. Bodies are eviscerated, limbs are scattered, and the cacophony is unrelenting. Yet, this brutality is not gratuitous—it is the necessary counterweight to Doss’s faith. For Doss’s refusal to touch a rifle to be truly miraculous, the threat must be absolute. The director treats the battlefield as a test of faith, where the sheer volume of destruction makes the idea of a "conscientious objector" seem initially absurd, and finally, divine. The visual language shifts from the chaotic to the singular, focusing on Garfield’s slender frame weaving through the smoke, not to take life, but to preserve it.

At the center of this maelstrom is Andrew Garfield, who delivers a performance of transcendent gentleness. Playing a saint is often a trap for actors—goodness can be boring—but Garfield imbues Doss with a nervous, twitchy energy that grounds his piety in humanity. He is not a stoic statue; he is terrified, exhausted, and trembling. The film’s emotional anchor is the sequence where Doss remains on the ridge alone after the retreat, lowering wounded men one by one down the escarpment. His mantra, "Lord, help me get one more," is whispered not as a boast, but as a desperate plea. It is here that the film transcends the war genre to become a study of radical empathy.

Ultimately, *Hacksaw Ridge* is a rebuke to the concept of the "anti-hero." In a cinematic landscape populated by morally grey protagonists, Gibson presents a character of uncompromising moral clarity. The film does not shy away from the horrific cost of war, but it suggests that even in the midst of the world’s most efficient machinery of death, the individual spirit remains indestructible. It is a blunt, bruising, and undeniably powerful work that argues that the strongest weapon on the battlefield was the only man who refused to carry one.