✦ AI-generated review

The Geometry of Childhood Fear

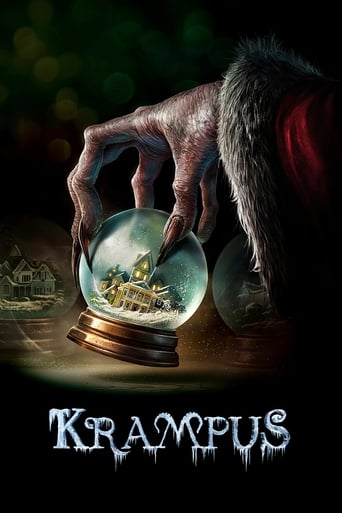

Horror is rarely about the monster. In the most enduring nightmares, the beast is merely a shape filled by the fluid, suffocating anxieties of its victims. Andy Muschietti’s 2017 adaptation of *It* understands this distinction with surgical precision. While it wears the costume of a summer blockbuster—complete with jump scares and a booming sound design—its true terror lies not in the sewers, but in the sun-drenched streets of Derry, Maine, where the silence of adults is more deafening than the roar of any creature.

Muschietti, stepping into the formidable shadow of Stephen King’s 1,100-page opus and the cultural memory of Tim Curry’s 1990 performance, chooses a distinct visual path. Collaborating with cinematographer Chung-hoon Chung (the eye behind Park Chan-wook’s *Oldboy*), the film rejects the grainy, blue-tinted gloom typical of modern horror. Instead, *It* is bathed in a pastoral, deceptive golden light. The cinematography captures the sweaty, tactile reality of a 1989 summer—the scratched knees, the rusty bikes, the humidity of the Barrens. This grounding makes the intrusion of the supernatural feel like a violation of the natural order. When the darkness does intrude, as in the Dutch angles of the Neibolt house or the claustrophobic darkness of the sewers, it feels like a cancer rotting the town from the inside out.

At the center of this rot is Bill Skarsgård’s Pennywise. If Curry’s interpretation was a sociopathic stand-up comedian, Skarsgård’s is a glitching, biological anomaly. He does not act human; he mimics humanity with a predator’s crude approximation. The brilliance of the performance lies in the micro-movements—the slight drift of a lazy eye, the wet, shameful drool that spills from his lip—suggesting a starving, ancient entity barely containing its hunger within a clown suit. He is not funny; he is an alien thing trying to lure food, and failing to hide its malice.

However, the film’s pulse beats strongest in the collective chest of the Losers Club. The script wisely isolates the children, creating a world where adults are either abusively present or terrifyingly absent. The horror is customized: for the hypochondriac Eddie, the monster is a leper, a manifestation of his mother’s suffocating Munchausen syndrome. For Beverly (a standout Sophia Lillis), the terror is a bathroom covered in blood that only she can see—a grotesque, undeniable metaphor for the onset of womanhood and the predatory gaze of her father. The "clown" is simply the final stroke on a canvas already painted with domestic trauma.

The narrative does occasionally buckle under the weight of its set pieces. The reliance on CGI-enhanced specters can sometimes strip the intimacy from the scares, replacing psychological dread with digital noise. Yet, when the film quiets down and focuses on the Losers standing by the quarry, staring into the dark water, it achieves a poignancy reminiscent of *Stand By Me*. It captures the specific tragedy of growing up: the realization that the people supposed to protect you are either incapable or unwilling to do so.

*It* succeeds because it treats childhood not as a time of innocence, but as a time of war. The film suggests that defeating the monster requires more than courage; it requires the painful acceptance of trauma. By the time the credits roll, the Losers have survived the clown, but the film leaves us with the melancholy understanding that they have also survived their childhoods, and that is a bell that can never be un-rung.