✦ AI-generated review

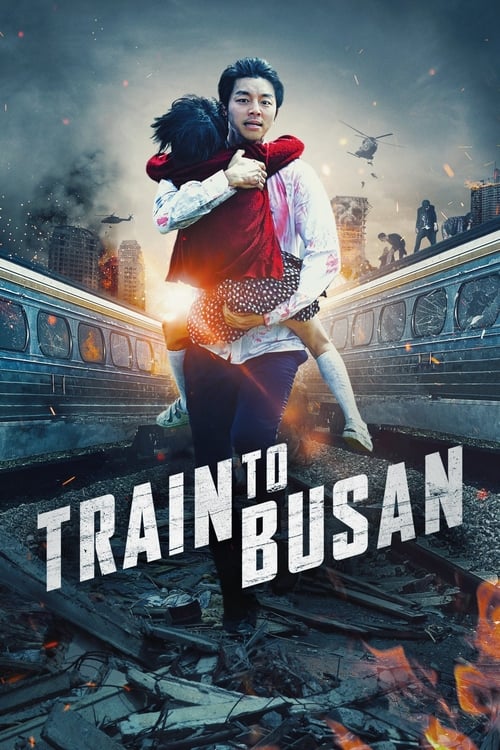

The Locomotive of Class Warfare

In the modern cinematic landscape, the zombie has largely devolved from a terrifying allegory into a video game sprite—a disposable target for headshots. Yet, in 2016, director Yeon Sang-ho, a filmmaker previously known for bleak, socially critical animation (*The King of Pigs*), dragged the undead back to their roots. *Train to Busan* is not merely a kinetic thrill ride; it is a claustrophobic pressure cooker of South Korean class anxiety, where the monsters outside the train are arguably less dangerous than the corporate rot within.

Yeon’s transition from animation to live-action is felt in the film’s visual vernacular. He treats the zombie horde not as individuals, but as a fluid dynamic—a literal flood of bodies that crash through glass and pour over seats like water bursting a dam. This is not the slow, shuffling dread of George Romero, but a frantic, rabid acceleration that mirrors the hyper-competitive pace of modern Seoul. The train itself, a gleaming silver bullet tearing through a dying country, serves as the perfect microcosm of a stratified society. The economy class, the first class, and the desperate spaces in between become the battlegrounds where humanity is tested, and frequently found wanting.

The film’s visual language is sharpest in its use of light and darkness. When the train plunges into tunnels, the infected go dormant, confused by the sudden blindness. In these moments of silence, the tension shifts from physical survival to moral calculation. It is in the dark that the film’s central question festers: Who deserves to be saved?

At the heart of this struggle is Seok-woo (Gong Yoo), a fund manager who begins the film as the embodiment of white-collar apathy. He is a man who "leeches off others," as described by the film’s moral anchor, the bruising working-class hero Sang-hwa (Ma Dong-seok). The genius of Yeon’s script is that it does not treat Seok-woo’s selfishness as a villainous quirk, but as a survival mechanism programmed by a neoliberal system. His initial instinct—to lock the door against others to save his daughter—is the logical endpoint of a society that prioritizes individual asset protection over communal safety.

The film’s most harrowing scene is not a zombie attack, but a human blockade. When Seok-woo and a small band of survivors fight their way through hell to reach a "safe" carriage, they are barred entry by the wealthy CEO Yon-suk and a mob of terrified passengers. This moment echoes the painful cultural memory of the Sewol Ferry tragedy—the catastrophic failure of authority figures and the fatal consequences of obeying the order to "stay put." The true horror is not the gnashing teeth of the infected, but the pristine suits of the uninfected who would sacrifice a child to maintain their own illusion of security.

Ultimately, *Train to Busan* argues that in an apocalypse, "every man for himself" is a suicide pact. The narrative arc bends painfully away from the cold logic of the fund manager toward the sacrificial love of the father. It suggests that while the virus destroys the body, it is the loss of empathy that destroys the soul. Yeon Sang-ho has crafted more than a summer blockbuster; he has delivered a humanist manifesto in the guise of a creature feature, reminding us that the train only moves forward if we are willing to hold the door open for those running behind us.