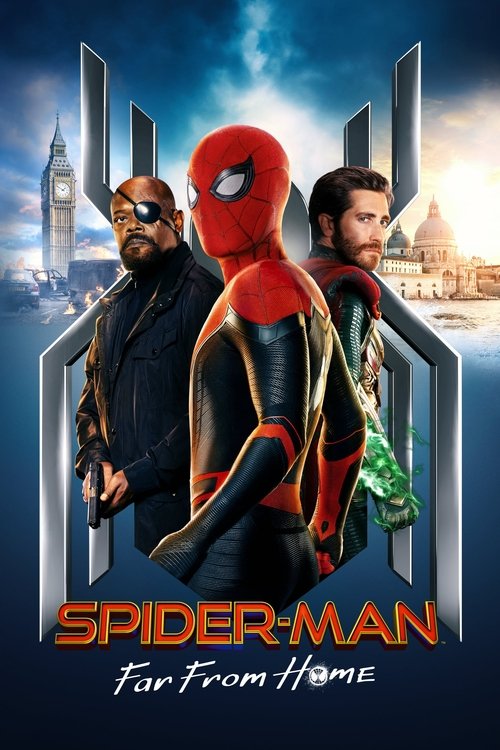

The Architecture of IllusionCinema often asks us to suspend our disbelief, but rarely does a blockbuster film weaponize that suspension against its own protagonist. Coming in the colossal wake of *Avengers: Endgame*, a film that operated with the funereal gravity of a state memorial, Jon Watts’ *Spider-Man: Far From Home* (2019) arrives not as a victory lap, but as a nervous hangover. It is a film preoccupied with the terrified question that haunts every successor: "Am I enough?" By displacing Peter Parker (Tom Holland) from the concrete canyons of Queens to the picturesque vistas of Europe, Watts strips away the "friendly neighborhood" safety net, forcing a grieving teenager to confront a world that demands a messiah when all he wants is a girlfriend.

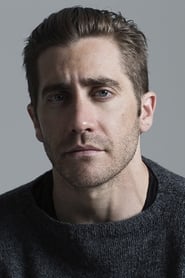

The film’s visual language is deceptively bright, utilizing the saturation of a travelogue to mask a darker undercurrent about the nature of truth. The central conflict here is not physical, but perceptual. In Quentin Beck, or Mysterio (played with theatrical relish by Jake Gyllenhaal), we find a villain perfectly calibrated for the post-truth era. Beck is not a monster; he is a director. He understands that in a world traumatized by "The Blip" and the loss of Tony Stark, the public does not need reality—they need a narrative. The visual effects in the film, particularly during the sequence where Beck traps Peter in a kaleidoscope of nightmarish hallucinations, are meta-textual brilliance. They reveal the CGI spectacle of modern superhero cinema as a terrifying construct, a "deep fake" weaponized to gaslight the hero and the audience alike.

At its heart, however, this is a study of impostor syndrome. Holland’s Peter Parker is vibrating with the anxiety of the inadequate. The script cleverly juxtaposes the cosmic stakes of saving the world with the microscopic, earth-shattering stakes of high school romance. Peter’s pursuit of MJ (Zendaya) is not a subplot; it is his primary motivation, the desperate grasp for normalcy in a life hijacked by duty. The chemistry between Holland and Zendaya is awkward, halting, and profoundly genuine, grounding the film’s fantastical elements in the tangible sweat of teenage nervousness. When Peter hands over Stark’s technology—essentially the keys to the kingdom—to Beck, it is not an act of stupidity, but an act of desperate relief. He is a child trying to give the crown to the first adult who acts like a father.

*Far From Home* ultimately argues that the legacy of Iron Man is not a suit of armor, but the burden of choice. By pitting Spider-Man against a villain who manufactures "fake news" and synthetic threats, the film forces Peter to trust his own "tingle"—his intuition—over the evidence of his eyes. It is a maturing of the character that feels earned rather than bestowed. In the end, Watts delivers a film that is breezy and comedic on the surface but deeply cynical about the performative nature of heroism. It suggests that in a world desperate for heroes, the most dangerous villains are the ones who know exactly what we want to believe.