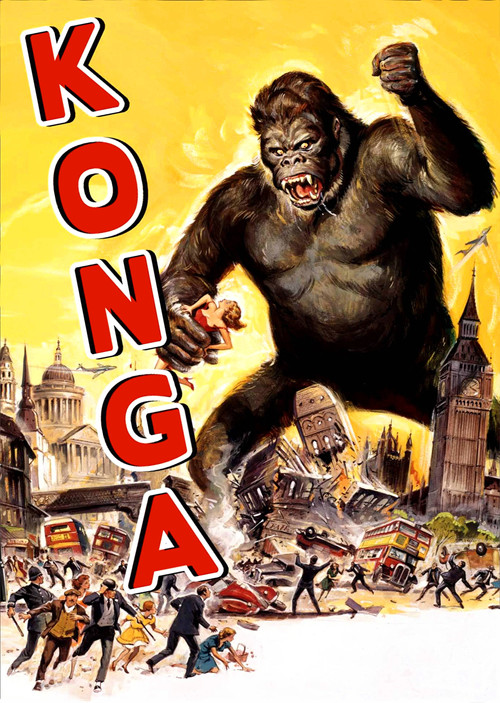

The Botany of EgoTo dismiss John Lemont’s *Konga* (1961) as merely another derivative entry in the "giant ape" subgenre is to ignore the distinct, delirious frequency on which it operates. While it was undeniably commissioned by producers Herman Cohen and Nat Cohen to capitalize on the evergreen popularity of *King Kong*, the resulting film is less an adventure of the natural world and more a claustrophobic portrait of colonial arrogance and unchecked narcissism. Where Kong was a tragedy of a noble beast in a foreign land, *Konga* is a tragedy of a small man who believes he is a god.

The film’s true monster is not the titular chimpanzee-turned-gorilla, but Dr. Charles Decker, played with a feverish, almost Shakespearean intensity by Michael Gough. Gough, a titan of British character acting, approaches the role not as a camp villain, but as a man consumed by a terrifying singularity of purpose. Returning from the African jungle after a year presumed dead, Decker brings with him not just a chimp, but a worldview that treats all living things—plants, animals, and women—as raw material for his own glorification. The film’s Technicolor palette, or "SpectaMation" as the marketing hyperbole dubbed it, renders London not as a gritty city, but as a saturated, dreamlike stage where Decker’s id can run rampant. The visual language here is one of garish excess; the greens of the carnivorous plants in Decker’s greenhouse are too bright, too plastic, suggesting a nature that has been perverted by synthetic ambition.

The central horror of *Konga* lies in its domestic dynamics. Decker’s relationship with his housekeeper and assistant, Margaret (Margo Johns), is a masterclass in manipulation. The script exposes a chilling misogyny that parallels Decker’s abuse of the natural world. He utilizes Margaret’s unrequited love to secure her silence, all while preying on a young student, Sandra. It is a suffocating triangular drama played out in a greenhouse, where the sexual tension is as palpable as the humidity required for Decker’s flesh-eating flora. When the ape is finally unleashed to dispatch Decker’s academic rivals, it feels less like a creature on the loose and more like an externalization of Decker’s own repressed rage—a psychic projection given fur and muscle.

The climax, featuring the giant simian towering over Big Ben, is frequently cited for its technical limitations—specifically the moment the ape clutches a limp, inanimate effigy of Decker. Yet, in the context of the film’s surreal logic, this artificiality becomes strangely poignant. Decker, having spent the film treating those around him as puppets, is finally reduced to a doll himself, held in the grip of the force he foolishly thought he could control. The special effects, provided by the budget-constrained team, create a dislocated reality that feels more akin to a nightmare than a blockbuster spectacle.

Ultimately, *Konga* stands as a fascinating artifact of British horror cinema. It is a film that transcends its exploitation roots through the sheer force of Michael Gough’s commitment. He anchors the absurdity with a gravity that demands attention, turning a creature feature into a cautionary tale about the toxicity of the intellectual ego. It is a garish, loud, and unexpectedly gripping examination of what happens when a man tries to play God, only to find he is merely a plaything.