✦ AI-generated review

The Currency of Chaos

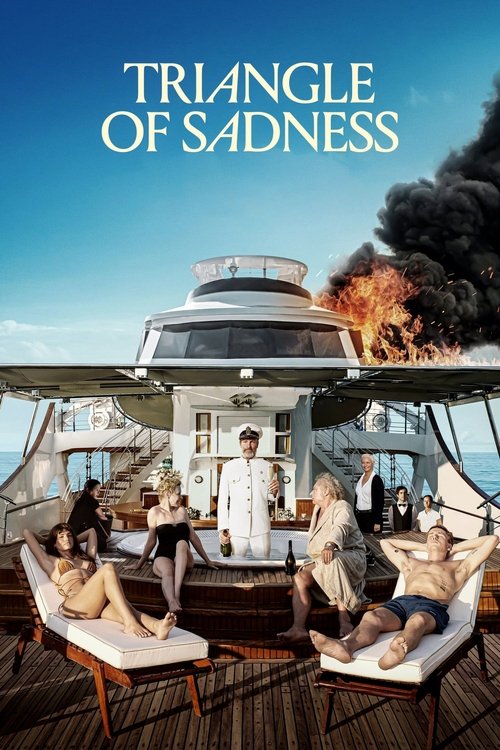

Ruben Östlund serves his satire not with a scalpel, but with a sledgehammer. In an era saturated with "eat the rich" narratives—from *The White Lotus* to *The Menu*—it is easy to dismiss *Triangle of Sadness* (2022) as just another entry in the canon of class resentment. Yet, to view it merely as a mockery of the one percent is to miss Östlund’s darker, more universal provocation. This is not simply a film about how wealth rots the soul; it is a terrifyingly funny examination of how quickly human civilization collapses into barbarism the moment the Wi-Fi cuts out and the toilets overflow.

Östlund, a two-time Palme d'Or winner, constructs the film as a triptych of escalating humiliation. He begins not with the rich, but with the beautiful. In the first act, we meet Carl (Harris Dickinson) and Yaya (the late, luminous Charlbi Dean), models whose relationship is a transactional currency. The director’s visual language here is clinical and claustrophobic. During an excruciatingly long argument over a restaurant bill, the camera refuses to cut away, trapping us in the silence of their gendered power struggle. Östlund forces the audience to sit in the discomfort, exposing the fragility of modern masculinity and the calculated coldness of "influencer love."

The film’s visual stability violently erodes in the second act, set aboard a luxury yacht. Here, the director unleashes his most infamous set piece: the Captain's Dinner. As a storm rages, the camera tilts and sways with nauseating precision, mirroring the inner equilibrium of the guests. The sequence is a grotesque ballet of bodily fluids, but its brilliance lies in the audio. Over the PA system, the ship’s drunk, Marxist captain (Woody Harrelson) and a Russian capitalist oligarch (Zlatko Burić) trade political quotes like philosophical punches. It is a cacophony of failed ideologies screaming into the void while the ship literally sinks in shit. Östlund suggests that neither Marx nor Rand can save you when physics decides to capsize your world.

However, the film finds its true emotional and philosophical weight in the third act, on the island. This is where the narrative moves beyond caricature to a profound anthropological study. When the survivors wash ashore, the hierarchy of the yacht—based on net worth—is instantly replaced by a hierarchy of competence. Abigail (a powerhouse Dolly de Leon), the ship’s toilet manager, becomes the dictator solely because she knows how to fish and build a fire.

What makes this shift so devastating is not that Abigail is a benevolent liberator, but that she immediately replicates the oppression she once served. She withholds food and demands sexual favors from Carl, mirroring the exploitation of the old world. Östlund grants no nobility to the oppressed; he posits that the drive to dominate is not a capitalist flaw, but a human one.

*Triangle of Sadness* is a loud, messy, and occasionally blunt film, but its lack of subtlety is its point. It argues that our social contracts are as thin as a modeling contract. In the end, we are left staring at the "triangle of sadness"—that worry line between the eyebrows—realizing that whether we are wearing Balenciaga or rags, we are all just one storm away from eating each other.