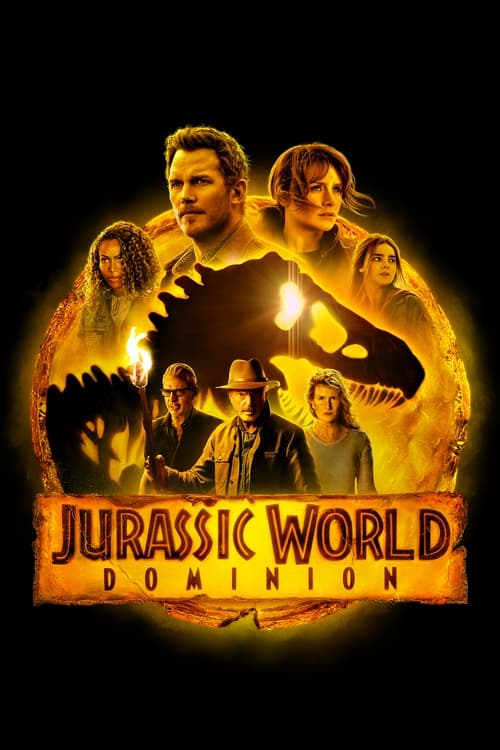

The Fossilization of WonderThere is a distinct melancholy in watching a film that possesses the resources to do anything, yet chooses to do the mundane at the highest possible volume. Colin Trevorrow’s *Jurassic World Dominion* arrives not merely as a sequel, but as a promised culmination—a cinematic event meant to fuse the DNA of Spielberg’s original masterpiece with the high-octane excess of the modern trilogy. The previous entry, *Fallen Kingdom*, ended with a tantalizing, terrifying thesis: the park is gone, and the prehistoric giants are now our neighbors. We were promised a new world order where humanity must negotiate its survival against the apex predators of history. Instead, strange as it is to say, we received a film about bugs.

It is difficult to overstate how oddly *Dominion* pivots from its own premise. While the film opens with a montage suggestive of a planet reshaped by roaming sauropods and nesting pteranodons, the narrative quickly abandons the sociological implications of "dinosaurs among us" to settle into a rote techno-thriller. Trevorrow, returning to the director’s chair, seems less interested in the awe of the natural world than in the mechanics of a spy caper. The visual language shifts drastically from the patient, terror-laden blocking of 1993 to the frantic, shaky-cam aesthetic of a Jason Bourne imitation. Nowhere is this more evident than in the Malta sequence, a frenetic motorcycle chase involving laser-guided raptors. The technical craft is undeniable, yet the sequence feels untethered from the franchise’s soul; it is kinetic noise, substituting speed for the suffocating tension that once made a rippling cup of water the scariest image in cinema.

The film’s greatest selling point—the reintegration of the legacy trinity: Sam Neill, Laura Dern, and Jeff Goldblum—is both its saving grace and its most frustrating concession. watching Dr. Grant and Dr. Sattler share the screen again evokes a genuine, unforced warmth that the modern protagonists, for all their athletic prowess, simply cannot generate. However, the script essentially strands these beloved icons in a subplot involving corporate espionage and genetically modified locusts. Yes, the central threat driving the plot of this dinosaur conclusion is a swarm of oversized insects threatening the world's grain supply. While the concept of ecological collapse via genetic tampering is thoroughly Crichton-esque, framing the grand finale of a dinosaur saga around wheat-eating pests feels like a miscalculation of the audience’s emotional investment. We came for the majesty of the *Therizinosaurus*; we stayed for a lecture on agribusiness.

Ultimately, *Dominion* suffers from a fear of silence. It is a film that crowds every frame with characters, creatures, and subplots, seemingly terrified that if the action stops for a moment of quiet reflection, the illusion will shatter. By corralling the cast into yet another isolated sanctuary (Biosyn Valley) for the third act, the film reneges on the promise of a global dinosaur pandemic, retreating to the safety of the very "park" formula it claimed to have outgrown. It is a loud, chaotic, and occasionally entertaining spectacle, but it lacks the reverence for life that defined the original. The dinosaurs are no longer animals to be understood; they are obstacles to be outrun, rendering the film a fossil of a bygone era of blockbuster filmmaking—massive, imposing, but devoid of the spark of life.