✦ AI-generated review

The Clockwork of Chaos

There is a specific kind of melancholy that hangs over a reformed villain. In cinema, the antagonist is often the engine of change—the agent of chaos who forces the world to react. When that agent is domesticated, as Felonious Gru has been for over a decade, the narrative must work twice as hard to find its pulse. *Despicable Me 4*, directed by returning architect Chris Renaud, attempts to solve this problem not by deepening the stakes, but by widening the canvas until it nearly bursts. It is a film that operates less like a traditional story and more like a high-speed centrifuge, spinning a dozen disparate elements—a new baby, a vengeful rival, a witness protection subplot, and superpowers—hoping that motion alone will generate heat.

Renaud, who helped define the series’ rubbery, kinetic aesthetic in the original 2010 film, returns here with a visual language that is as polished as it is frantic. The animation remains a marvel of elasticity; characters do not merely move, they bounce, stretch, and snap with the logic of a Chuck Jones short. This is most evident in the film’s controversial "Mega Minions" subplot, where the ubiquitous yellow henchmen are gifted superpowers. Visually, these sequences are a feast of textures—stretchy rock skin, laser beams cutting through cheese—but they also represent the film’s central tension. The imagery is spectacular, yet it feels untethered, a series of visual gags floating in a vacuum, disconnected from the emotional gravity that once grounded Gru’s journey.

At the heart of this kaleidoscope is the relationship between Gru and his infant son, Gru Jr. It is here that the film attempts to locate its humanity. The dynamic is a classic inversion: the man who once stole the moon is now desperate for the affection of a toddler who prefers his mother. There is a genuine, albeit slapstick, sweetness in Gru’s struggle. He is no longer fighting to be the world's greatest villain; he is fighting to be a relevant father. The heist sequence at the *Lycée Pas Bon*, where Gru and his son must work together to steal a honey badger, serves as the film’s strongest metaphor. It is a dance of generational friction, where the father’s old-school stealth clashes with the son’s chaotic whims, reminding us that parenting is, in itself, a high-stakes heist with no guarantee of success.

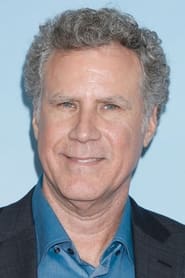

However, this emotional core is frequently drowned out by the noise of the antagonist, Maxime Le Mal. Voiced by Will Ferrell with a flamboyant French accent, Maxime is a villain designed around the motif of the cockroach—indestructible, pests, and fundamentally repulsive. While the character design is inventive (his bio-mechanical cockroach suit is a triumph of grotesque animation), he functions more as a plot device than a true foil. Unlike Vector, who represented the future Gru feared, Maxime is merely a ghost from the past, a grudge holder whose motivation feels thin. The choice to thematically link the villain to a cockroach is perhaps an accidental meta-commentary on the franchise itself: it has become an entity that can survive anything, adapting to every environment, impossible to stomp out.

Ultimately, *Despicable Me 4* is a study in narrative entropy. It is a film that refuses to sit still, perhaps afraid that silence would reveal the thinness of its script. Yet, to dismiss it entirely is to ignore the artistry of its execution. There is a rhythm to its madness, a precise comedic timing in its chaos that few studios can replicate. It does not challenge the viewer, nor does it expand the medium, but it offers a comforting, manic consistency. It is a film that asks nothing of us but to watch the colors spin, a temporary suspension of gravity that leaves us exactly where we started, only slightly more dizzy.