✦ AI-generated review

The Gilded Cage of Adolescent Desire

Cinema has long served as a mirror for our collective anxieties, but in the algorithmic age, it increasingly serves as a mirror for our collective obsessions. Jenny Gage’s *After* (2019) is a fascinating artifact of this shift—a film born not from a screenwriter’s original spark, but from the digital ether of Wattpad fanfiction. Adapted from Anna Todd’s viral writing, which reimagined Harry Styles as a brooding literary sadboy, the film arrives on screen less as a story and more as a monument to teenage id. It is a work that inadvertently asks a troubling question: What happens when we polish our most regressive fantasies until they gleam?

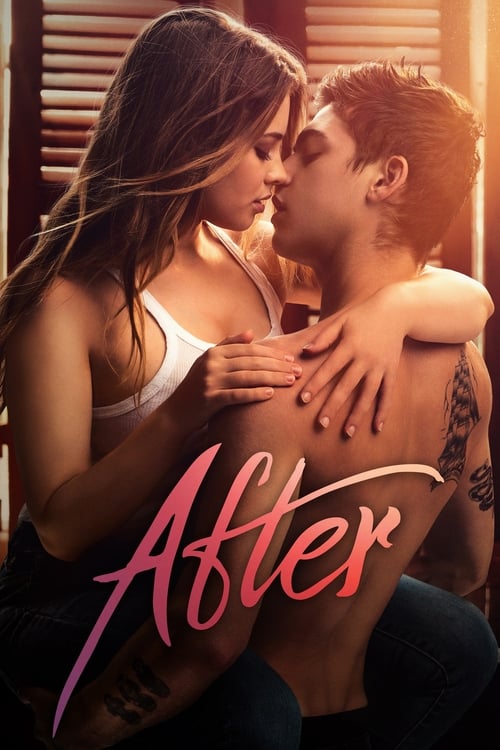

To dismiss *After* merely as "bad" is to miss the distinct, almost hypnotic texture of its failure. Gage, whose background lies in fine art photography and documentary (specifically the raw, observant *All This Panic*), bathes the film in a lush, sensory aesthetic that is completely at odds with its juvenile narrative. The visual language here is not the flat, bright lighting of a standard teen rom-com; it is moody, tactile, and suffocatingly close. Gage shoots the actors, Josephine Langford and Hero Fiennes Tiffin, with a reverence usually reserved for religious icons or high-end perfume commercials. The camera lingers on a hand grazing a cheek, the ripple of water in a lake, or the ink on skin, creating a dreamscape that feels hermetically sealed from the real world.

This visual seduction reaches its apex in the widely discussed "lake scene." Here, the film sheds its dialogue—which is often wooden and laden with clichés—and relies entirely on atmosphere. The water is still, the lighting is ethereal, and for a moment, the audience is invited to believe in the profundity of the connection between Tessa and Hardin. It is a triumph of direction over script, a moment where the "how" of the film briefly convinces us to ignore the "why." Gage wraps the toxicity of the central relationship in such beautiful packaging that the viewer is almost lulled into complicity.

However, once the spell breaks, the narrative collapses under the weight of its own archaism. The central conflict—the innocent freshman corrupted by the damaged bad boy—is a trope so worn it has become translucent. The film attempts to intellectualize this dynamic by having the characters debate *Pride and Prejudice* in a literature class, a scene that feels less like character development and more like a desperate plea for legitimacy. But unlike Darcy and Elizabeth, whose friction was born of wit and class struggle, Hardin and Tessa’s friction is born of manipulation and projection. Hardin is not a complex Byronic hero; he is a collection of red flags engaging in emotional cruelty, which the film mistakes for passion.

Ultimately, *After* is a film at war with itself. It possesses a director with a keen eye for intimacy and the terrifying vulnerability of youth, trapped within a story that glorifies the destruction of that vulnerability. It is a beautifully shot void, a gilded cage where the characters are trapped not by circumstance, but by the limitations of the fanfiction archetypes they were born from. It stands as a testament to a modern cinematic paradox: we have never had better tools to tell stories, yet we are increasingly using them to retell the same toxic fairy tales, hoping that this time, the aesthetic will be enough to save us.