✦ AI-generated review

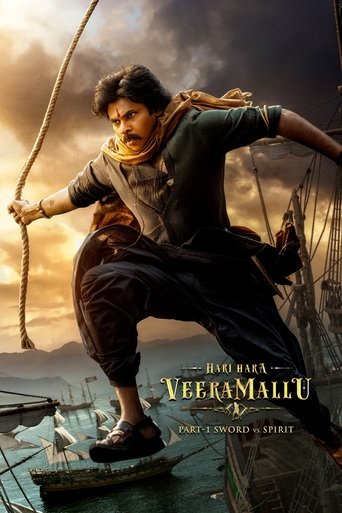

The Architecture of Awe

In an era where the global blockbuster has become synonymous with cynical irony—where superheroes wink at the camera to apologize for their own absurdity—S.S. Rajamouli’s *RRR* arrives like a thunderclap of unashamed sincerity. It is a film that rejects the modern Hollywood tendency to deconstruct the hero; instead, it reconstructs him with the weight of myth and the velocity of a freight train. To view *RRR* merely as an action movie is to misunderstand its ambition. It is a kinetic opera, a three-hour testament to the belief that cinema’s primary duty is not to reflect reality, but to amplify emotion until it breaks the laws of physics.

Rajamouli’s visual language is built on a foundation of "emotional physics." In his world, gravity is a suggestion, subservient to the narrative stakes. Consider the film’s inciting bridge rescue sequence, where the protagonists—Alluri Sitarama Raju (Ram Charan) and Komaram Bheem (N.T. Rama Rao Jr.)—meet for the first time. They do not exchange words; they exchange a glance, a nod, and then a synchronized, gravity-defying leap to save a child from a burning train car. A lesser director might attempt to ground this in gritty realism; Rajamouli shoots it like a divine intervention. The flag, the fire, and the handshake under water are not just stunts; they are the visual thesis of the film: these men are elemental forces (Fire and Water) destined to collide. The CGI serves the melodrama, creating a suffocating sense of scale that makes the emotions feel as large as the explosions.

At the heart of this spectacle lies a profoundly human story of male friendship, elevated to the level of the *Ramayana* and the *Mahabharata*. The film creates a fictionalized meeting between two real-life Indian revolutionaries who never met in history, turning their bond into a tragic romance of duty versus devotion. Ram, the officer in the police uniform, simmers with the stoic heat of a man who must play the villain to save his people. Bheem, the gentle shepherd with the strength of a titan, flows with the transparency of water, driven only by the need to rescue a stolen child.

The brilliance of the screenplay (written by Rajamouli and V. Vijayendra Prasad) is how it navigates their inevitable betrayal. The conflict isn't generated by a misunderstanding, but by the collision of two righteous causes. Even the film’s most famous sequence, the "Naatu Naatu" dance number, functions as a battle scene. It is not a break from the narrative but an expression of anti-colonial resistance through joy. When Ram and Bheem synchronize their steps against the sneering British elite, they are weaponizing their culture. The scene works because it treats the dance with the same tactical intensity as the film’s prison breaks or tiger fights.

There is, of course, a complex conversation to be had about the film's political subtext and its use of Hindu iconography to mythologize history. By the final act, the transformation of Ram from a soldier into a literal deity-like figure armed with a bow blurs the line between historical fiction and religious exaltation. Yet, purely as a piece of filmmaking, *RRR* succeeds because it possesses a heartbeat that most franchises have long since replaced with algorithms. It reminds us that the "big screen" was invented not just for size, but for scope—to hold stories too large, too loud, and too passionate for the real world to contain.