The Architecture of AwakeningTo watch *The Matrix* in 1999 was to witness a fissure in the cinematic landscape, a moment where the anxieties of the analog world collided violently with the promises of the digital age. To watch it now, over two decades later, is to realize that Lana and Lilly Wachowski did not merely create a sci-fi blockbuster; they drafted a manifesto for the modern soul. Beneath the leather trenches and kinetic violence lies a profoundly tender exploration of identity, a gnostic parable about the terrifying ecstasy of waking up.

The film operates on a visual frequency that felt alien upon release and now feels like prophecy. The Wachowskis, collaborating with cinematographer Bill Pope, established a binary aesthetic that serves the narrative’s central deception. The world of the Matrix is washed in a sickly, fluorescent green—a decayed digital construct designed to numb the senses. In contrast, the "real world" of the Nebuchadnezzar is cold, blue, and industrial, yet undeniable in its tactile grit.

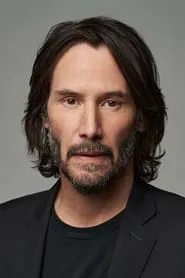

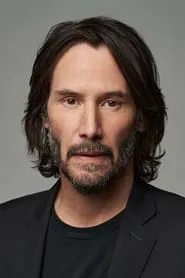

This visual dissonance prepares us for "bullet time," the film's most famous technical innovation. But to view this merely as a special effect is to miss the point. When Neo (Keanu Reeves) leans backward on that rooftop, the camera detaching from the laws of physics to orbit him, it is not just a cool shot; it is the visual expression of consciousness expanding. It is the moment a character realizes that the rules of their existence are arbitrary, written by an authority that can be defied. The camera moves because Neo’s mind has moved.

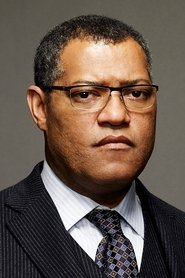

At the heart of this spectacle is a surprisingly intimate human struggle. Keanu Reeves, often criticized for a perceived stiffness, is perfectly cast here as a vessel of uncertainty. His Neo is not a confident action hero but a confused somnambulist waiting to be startled awake. The famous "Red Pill" scene with Morpheus (Laurence Fishburne) is the film’s philosophical fulcrum. It frames the central question not as a battle between good and evil, but between comfort and truth. The horror of *The Matrix* is that the "truth" is not a paradise; it is a scorched earth, a grim existence of gruel and shivering in the dark. The heroism lies in choosing that darkness solely because it is *real*.

We cannot discuss *The Matrix* today without acknowledging its metamorphosis in the cultural consciousness. While it began as a cyberpunk interpretation of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, it has revealed itself, through the lens of the directors' own lives, as a potent allegory for transition and self-actualization. The concept of a "splinter in your mind"—the feeling that your assigned reality does not fit your internal truth—speaks to anyone who has ever felt marginalized by the systems governing their identity.

Ultimately, *The Matrix* endures because it respects the intelligence of its audience. It marries the kinetic joy of Hong Kong cinema with the cerebral density of Baudrillard, refusing to sacrifice one for the other. It suggests that liberation is not a destination, but a continuous, often violent process of unlearning. We are still unplugging, still squinting against the light, still asking if we are awake.