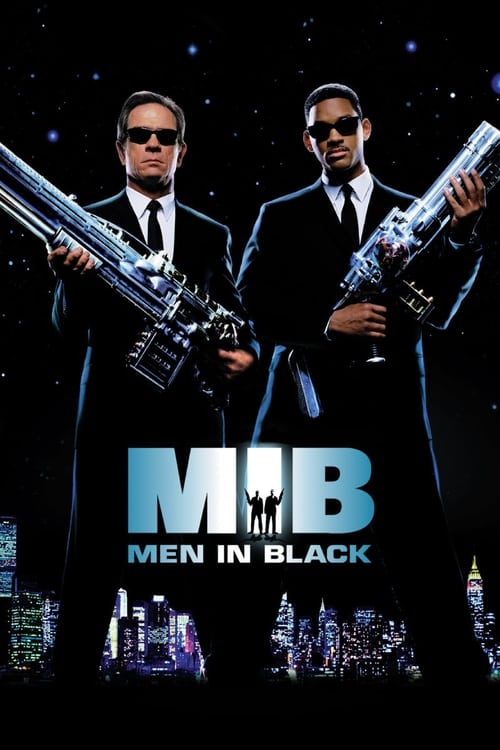

The Immigrant and the InfiniteIn the summer of 1997, amidst a cinematic landscape often dominated by bombastic disaster epics and earnest heroism, Barry Sonnenfeld’s *Men in Black* arrived not with a bang, but with a weary sigh and the flash of a neuralyzer. While ostensibly a summer blockbuster about aliens, to view it merely as an action-comedy is to miss its surprisingly melancholy heart. It is a film that treats the discovery of extraterrestrial life not as a spiritual awakening, but as a logistical nightmare—a paperwork hazard managed by men in indistinct suits who have surrendered their identities to maintain the illusion of a normal world.

Sonnenfeld, a former cinematographer for the Coen Brothers, brings a distinct visual claustrophobia to the vastness of the universe. He rejects the soaring, reverent wide shots typical of Spielbergian sci-fi in favor of aggressive, distorting wide-angle lenses. By pushing the camera uncomfortably close to his subjects (often using 10mm to 21mm lenses), he creates a grotesque hyper-reality where New York City feels as alien as the creatures inhabiting it. The visual language suggests that the world is already warped; Agent K (Tommy Lee Jones) and Agent J (Will Smith) are merely the ones with the spectacles to see it. The CGI, while dated, retains a tactile, rubbery charm that fits this heightened aesthetic, grounding the impossible in the grimy texture of the city.

At its narrative core, *Men in Black* is a surprisingly poignant parable about immigration and assimilation. The film opens not with an invasion, but with a border patrol interception. The joke—that the "illegal aliens" are literally from off-world—is played not for malice but for a matter-of-fact acceptance of a chaotic universe. Agent K does not hunt these beings because they are different; he polices them because they have broken the bureaucratic compact. The film portrays Earth not as a fortress to be defended, but as an interstellar refugee camp—a "Casablanca without the Nazis," as the script implies. There is a radical empathy in the way K interacts with the worm-guys in the breakroom or the squid-baby being born in the back of a car. To him, they are just commuters trying to get by.

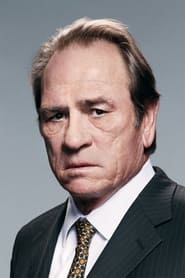

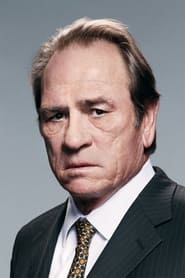

This empathy is counterbalanced by the film’s pervasive sense of isolation. The true cost of the "black suit" is not the physical danger, but the erasure of the self. Tommy Lee Jones delivers a performance of masterful minimalism; his Agent K is a man hollowed out by secrets, holding the weight of the galaxy in a silence so profound it becomes his defining trait. He plays the straight man not just to Will Smith, but to the absurdity of existence itself. Smith, in turn, offers more than just kinetic energy; his Agent J acts as the audience’s tether to humanity. His initiation—the famous scene where he drags a heavy table across the floor while other recruits struggle with written exams—demonstrates that the job requires not just skill, but an ability to rewrite the rules of engagement.

Ultimately, *Men in Black* is a film about perspective. It constantly reminds us of our cosmic insignificance—most famously in its closing shot, which zooms out to reveal our entire galaxy is merely a marble in a game played by colossally larger entities. This could be terrifying, a plunge into nihilism. Yet, under Sonnenfeld’s direction, it becomes strangely comforting. If we are small, then our problems are small. If the apocalypse is just a Tuesday for the Men in Black, then perhaps we can afford to take ourselves a little less seriously. It is a masterpiece of tone, balancing the slime of the gutter with the starlight of the infinite.

The Verdict:

The Verdict: A rare blockbuster that manages to be cynical about bureaucracy yet deeply humanistic about the "other." It stands as a sharp, stylish, and unexpectedly soulful examination of what it means to belong in a universe too big to comprehend.